I was recently told that stage blood comes in three “flavors”: regular (kinda corn-syrupy), sugar-free, and mint. This peculiar tidbit may linger in your mind as you watch the Philadelphia Artists’ Collective’s noirlike staging of THE WHITE DEVIL, in PAC’s final production at their Broad Street Ministry home.

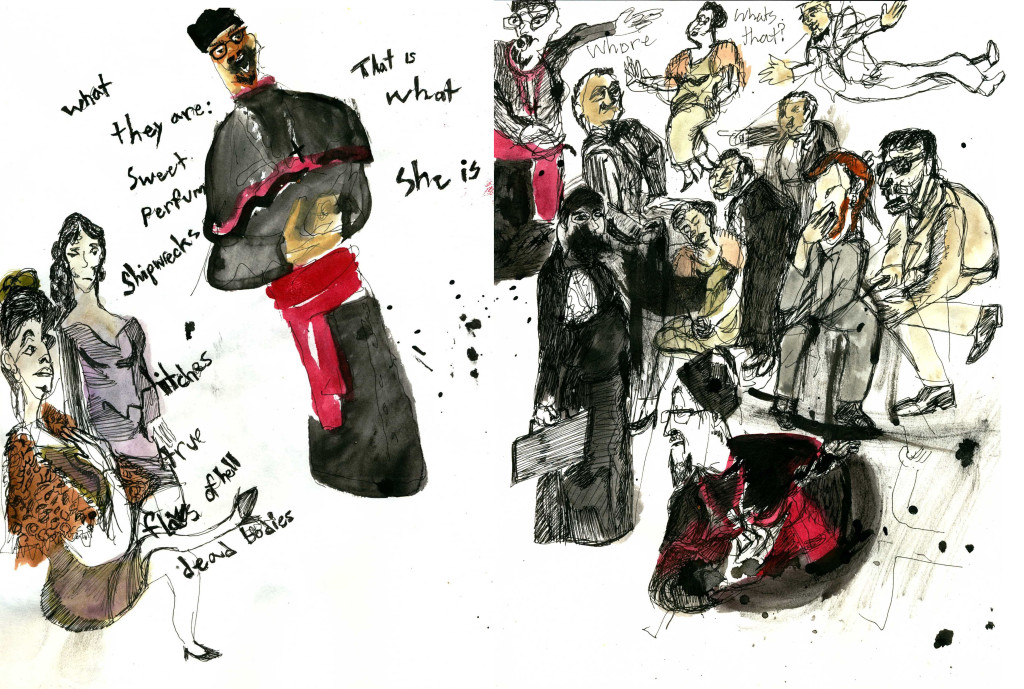

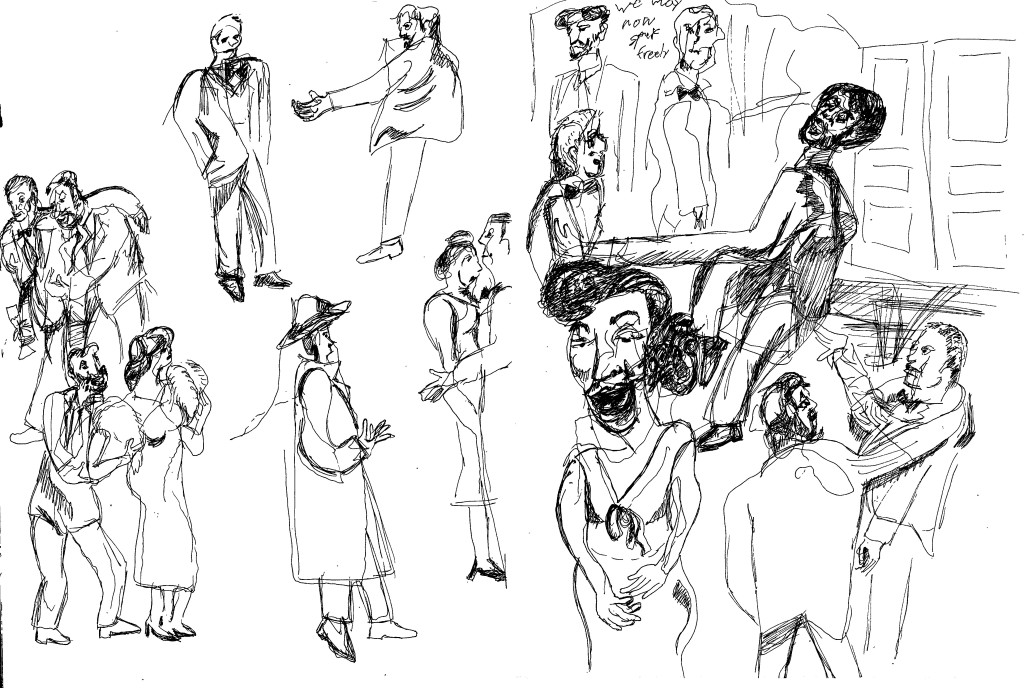

As a true Jacobean tragedy, John Webster’s 1612 play moves inexorably from sugar-free foreboding to a mint-scented blood-bath. We follow the machinations of Flamineo (the intelligent, darkly funny Dan Hodge) a striving servant who hopes to forge a coupling between his master Brachiano (quietly complex Jared Reed) and sister Vittoria (powerful Charlotte Northeast).

The match is unsurprisingly opposed by the pair’s respective spouses, Vittoria’s husband Camillo (played as an endearing bumbler by Adam Altman) and Bachiano’s loyal wife Isabella (given a fitting nobility by Mary Lee Bednarek). Isabella’s brother Francisco (smartly dignified John Lopes) and clergyman Monticelso (Brian McCann, in another strong and amusing performance in a season replete with them) plot to foil Flamineo and Bachiano, and to revenge their murderous ploys.

This synopsis merely scratches the surface of a convoluted yet compelling plot. At times, the various strands are weighed down in side-plots and “who is this character again?” reappearances (complicated further by necessary dual castings). That PAC’s production remains engaging for its 2 ½-hour running time is a testament to the quality of its performances (evident in my parenthetical descriptions) and a clear directorial vision from Damon Bonetti.

With the help of costume designer Katherine Fritz, Bonetti gives the late Shakespearean-era tragedy the veneer of a mid-20th century hard-boiler. The device succeeds admirably, Webster’s plot unfolds like a mystery, with more murders and plot twists than a paperback thriller. As with other PAC productions, the centuries-old piece never feels archaic, and its modern-if-not-contemporary setting never feels slapped on or anachronistic.

As Bonetti and his players realize and respect, Webster’s themes remain relevant: Flamineo’s desire for power, the jealousies and irrationality of love, the unexpected victims of our actions. Similarly to the plot, the script is almost sententious in its superb pithyness.

“Small mischiefs are by greater made secure,” says Brachiano. Bloodily true until it bloodily isn’t. Bloody good stuff.

[Broad Street Ministry, 315 S. Broad Street] May 3-20, 2017; philartistscollective.org