New Freedom Theatre’s THE BALLAD OF TRAYVON MARTIN is an ambitious retelling of the last seven hours of the 17-year-old’s life.

The play opens with an overlay of voiceovers from several influential figures, the most prominent and haunting being the mother of Emmet Till (an African American teenager lynched in Mississippi in 1955). Immediately the audience is encouraged to make a mental connection between Till’s injustice and Trayvon Martin’s. The voiceovers are accompanied by two dancers dressed in hoodies and caps, who move through space until the curtain opens and remain onstage for most of the production.

The opening sequence, in all its originality and strangeness, is a precursor to the play’s abstract storytelling style. THE BALLAD OF TRAYVON MARTIN has a dreamlike structure that situates it more as a creative outlet for grief than an actual retelling of events. Scenes are depicted out of order. The set, designed by Parris Bradley, is a huge set of stairs leading to a (foreboding? inviting?) pair of enormous black gates (we don’t find out until the end that Trayvon is being inducted into heaven); the dialogue, more poetry than conversation, comes through in several emotionally charged monologues from Trayvon’s mother Sybrina (Angel Brice) and father Tracy (Shabazz Green), as they take turns mourning the death of their son. In-between are a few scenes where we get to witness Trayvon (Amir Randall in a spectacularly fitting performance) interacting with his parents: A basketball game with his father, an endearing back-and-forth with his mother, and few other moments offer us brief glimpses of actual human interaction.

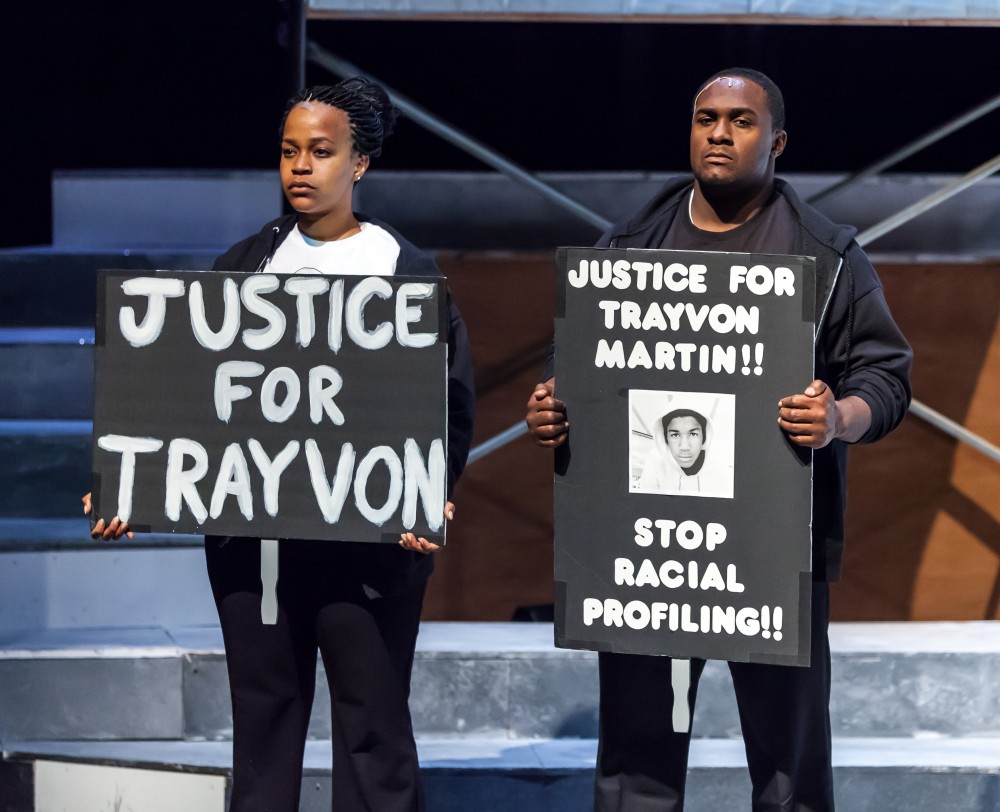

The play doesn’t really have a story, and rightly so—we know Trayvon’s all too well. What the play does seem to have, though, is an agenda. Much of it is made up of preachy protests and sermons, with groups of actors holding picket signs that read “I AM TRAYVON MARTIN”, and chanting to incite the audience. Christopher David Roche portrays a ruthless, dim-witted, foul-mouthed George Zimmerman; he and the two other white cast-members take on several roles, none of which are redeeming in any way. Though that’s not what the play is about—advocating for the “good” white people who do actually exist in the world—it does very little to refute the notion that all whites are as evil as Zimmerman (it also underplays the fact that Zimmerman himself identifies as Hispanic).

The significance of these details didn’t strike me until during intermission, when a young boy in the audience, obviously enraged by what he saw onstage during the first half of the show, stood up and declared, “I officially hate white people now.” I turned around in my seat, wondering if anyone else had heard him. The guardians he was with, four adult women, looked at each other and laughed.

A similar situation occurred after a showing of An Octoroon at the Wilma Theatre. During a talkback, castmember Campbell O’Hare, who portrayed Zoey in the play, recalled the moment when a young boy approached her after a show and told her he had gotten so angry by what he saw in the play that he was praying that she (she assumed he was referring to her character) would be sold as a slave. O’Hare admitted she was speechless in response to the boy, and noted how guilty his comment made her feel, but also that she understood why he would feel that way.

I remember being mad as hell myself after watching An Octoroon. The use of blackface and slavery as comic devices and the depiction of white slavers, albeit to make a social point, left me feeling cold and bitter against my amused fellow audience members, most of whom were white. I left the theater that night feeling as if there was no way white people could empathize with me, that we were as unconnected and opposite as the black slaves and white masters depicted in the play.

THE BALLAD OF TRAYVON MARTIN obviously aroused similar reactions in its audience. This caused me to wonder why “black plays” focus so intently on making white people seem so terrible, unintentionally perpetuating an “us against them” attitude. While I know and understand that no two scripts are alike, I can only long for plays that carry themselves in the likes of acclaimed African-American playwright August Wilson’s, namely Two Trains Running (performed at the Arden earlier this year), which depicts people of color in a surprisingly more modern and relatable way (and with less smugness) than An Octoroon or THE BALLAD OF TRAYVON MARTIN, despite being written in the early 90s and set in the 60s. Two Trains Running employed no white actors and didn’t use white guilt as a tactic to seem more compelling; one might even say the play finds its black characters more critical of each other than those of the opposite race.

During the talkback following TRAYVON MARTIN, I asked the panel, which consisted of most of the cast, executive director Sandra Haughton, and a few guests, what reaction they were hoping to get out of the audience in light of the young boy’s comment. They all thought deeply for a moment, and then David Roche responded that he hoped the play would open up a dialogue within the community about this very issue.

“I would inform that little boy that what he feels is authentic,” said Sandra Haughton. But, “there is a more positive way to express these emotions.” She went on to say that she would suggest a better way to channel his anger, maybe a creative outlet such as music or theater.

Michael Fegley, who portrayed Zimmerman’s brother and acted other various small roles, recalled that his fifteen-year-old daughter cried for a very long time after seeing the play, expressing that she “felt guilty for being white.”

James Ijames admitted after An Octoroon that the play’s intention was “to make you feel something.” Anger certainly is a valid reaction to THE BALLAD OF TRAYVON MARTIN, An Octoroon, or any play that depicts racial injustice. We should try to learn, however, to hate the injustice, and not the color of the person behind it. The danger comes when we leave the theater feeling anger or hatred and have no idea what to do with it.

“It’s not going to solve anything,” said a guest panelist. “Anger can be something great, or anger can be a passion. Tracy Martin used his anger as a passion, and that’s why we have this play today.”

[New Freedom Theatre, 1346 N. Broad Street] May 11-22, 2016; freedomtheatre.org.

Needed more seasoned perfomers. Seemed very raw.

Actually the acting didn’t bother me much. Especially impressed by Amir Randall, who is only 16. Shabazz Green handled variety well in his multiple roles. Angel Bryce was good, but her roles weren’t distinguishable as she acted each one quite similarly.

I thought the writing, above all, needed improvement.

When you see a play, you are going for the acting and the story. If someone has several roles and they all seem similar, that’s not good. I agree the writing needs much improvement.