At the corner of 22nd and Ludlow streets sits the elegant red-brick structure which houses the College of Physicians, the oldest medical society in the country. At first glance, this staid institution seems an unlikely home for one of Philadelphia’s best-loved tourist destinations. But within the opulent Beaux Arts interior lies one of the most peculiar and enthralling collections of any museum in the world.

At the corner of 22nd and Ludlow streets sits the elegant red-brick structure which houses the College of Physicians, the oldest medical society in the country. At first glance, this staid institution seems an unlikely home for one of Philadelphia’s best-loved tourist destinations. But within the opulent Beaux Arts interior lies one of the most peculiar and enthralling collections of any museum in the world.

Shrunken heads, deformed fetuses, conjoined twins, rows upon rows of skulls, a distended 50-pound colon, a body which has turned into soap: these are just a few of the disturbing and macabre items on display at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia. Visitors today may be inclined to see these intriguing specimens as mere medical oddities. But this collection, the legacy of a charismatic nineteenth-century physician, provides a window into a lost world of medical practice and education.

Dr. Mütter and His Teaching Tools

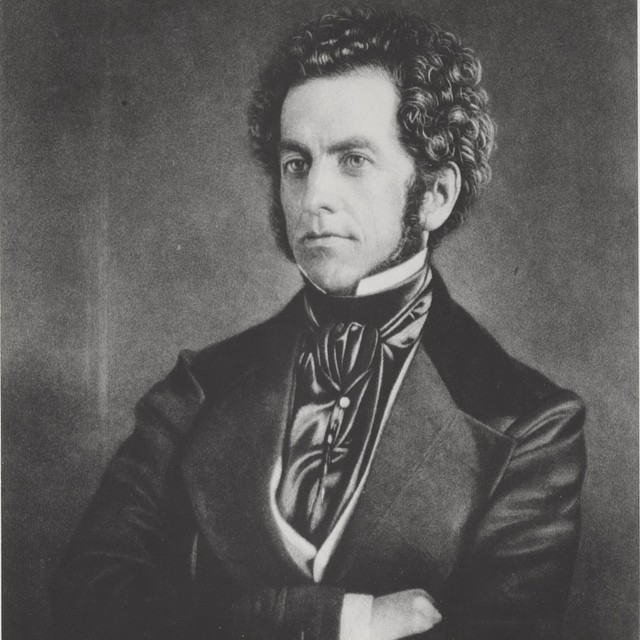

Born in Richmond Virginia in 1811, Thomas Dent Mutter lost his brother, mother, father, and guardian grandmother to illness by the time he was seven. As a sickly orphan, Mutter developed an interest in medicine, enrolling in the University of Pennsylvania medical school at age 17.

Then as now, Philadelphia was the leading city in the nation for medical education. Founded in 1765, Mutter’s alma mater was the first hospital and medical school in North America. Today, Penn is one of five med schools in the city educating nearly 20% of all doctors in America. Visitors to Philadelphia can still see the stately Pennsylvania Hospital building at 8th and Spruce streets.

After graduating from Penn, young Mutter followed the path of many American doctors of the time and continued his education among the surgeons of Paris, France. There he learnt the innovative techniques of les operations plastiques (plastic surgery): cosmetic procedures to repair skin and tissue damaged by burns, tumors, or congenital defects.

In Paris, Mutter obtained an item since seen by thousands of museum-goers: a wax head-cast of a “horned” lady, a young woman with a thick brown protrusion extending from her forehead to below her chin. It was the first of many wax models, skeletons, and preserved body parts he would collect over the next few decades.

On returning to Philadelphia, Mütter (as he now styled himself, adding an umlaut to appear more European) became a prominent plastic surgeon. He was soon named chair of surgery at Jefferson Medical College, the city’s second-oldest medical school (now Thomas Jefferson University). There, he used his growing collection of one-of-a-kind medical specimens as a teaching tool to demonstrate the varied maladies which could affect the human body. “He wanted a well-rounded collection,” says Robert Hicks, director of the Mütter Museum. “One that reflected what a physician might see in practice.”

At Jefferson, Mütter built a reputation as a flamboyant and popular lecturer, a precocious young doctor at the forefront of a wave of new surgical techniques. He was an early adopter of anaesthesia and sterilization, developments which made operations significantly less painful and risky. Tickets to his public surgeries were a hot commodity, and aspiring students praised his teaching skills and the specimens from his growing collection, which he wove into his lectures “so as to impress yet not confuse,” as he wrote at the time.

The later years of Mütter’s life were plagued by illness, including painful attacks of gout—a swelling of the joints often caused by poor nutrition—which made it impossible for the doctor to perform surgeries. Seeing that his days were numbered, the physician sought a permanent home for his extensive holdings of pathological specimens, waxworks, and diagrams so that they would be useful to future generations of doctors.

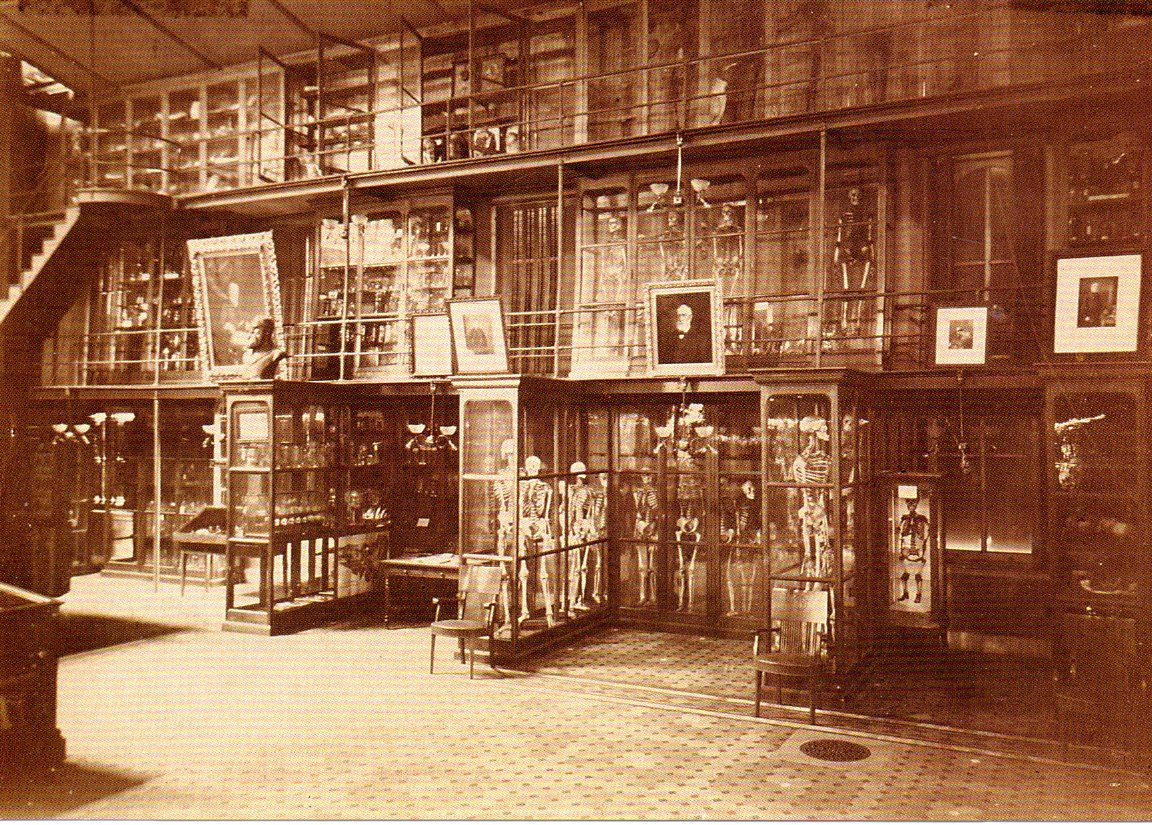

Mütter stipulated that his collection be housed in a dedicated fireproof building. His first choice venue, Jefferson Medical College, baulked at the expense, so Mütter turned to the College of Physicians. Founded in 1787, the College was not a school but a professional medical society, the largest in the country. The society was already planning to move into a new home and was willing to accommodate Mütter’s request for a new building, especially given the doctor’s offer of a $30,000 bequest to house and care for his collection. In 1858, a few months before he died at the age of 47, Mütter signed an Article of Agreement transferring his holdings to the College of Physicians.

When the museum opened in 1863, the collection numbered about 1,700 items, of which more than 1,300 survive. Among them are the preserved swollen hand of a gout sufferer, the aforementioned “horned lady”, and the skeleton of a female frighteningly malformed by years of wearing restrictive corsets. Over the next several decades, the museum added many other items aligned with Dr. Mütter’s original donation.

A Growing Collection

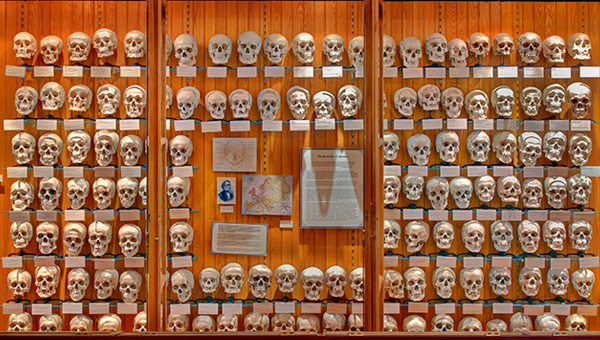

In 1874, the museum obtained the death cast and fused liver of conjoined brothers Chang and Eng, remembered in the name “Siamese Twins”. That same year, it purchased a set of 139 skulls from Austrian physician Joseph Hyrtl. A body from the 1830s of a woman turned almost completely to soap made its way to the museum in 1875. Other items donated to the Mütter Museum in the 1800s continue to amaze visitors today: a nine-foot, 50-pound colon from a man who died of constipation; the tumor removed from President Grover Cleveland’s jaw; shrunken heads from the Shuar people of Peru.

The collection continued to grow in the twentieth century. In 1924, surgeon Chevalier Jackson donated over 2,000 foreign objects (buttons, needles, toys, etc.) extracted from the bodies of his patients. The body of Harry Eastlack, whose muscles had turned to bone due to a rare disorder, was given to the museum after his death in 1973.

The collection now contains more than 20,000 objects and continues to grow, most recently with the acquisition of slices of Albert Einstein’s brain. But the museum retains a distinctly Victorian feel. “The nineteenth-century weirdosity is part of the appeal,” says museum director Robert Hicks. Large wooden display cabinets and fading text labels make it seem almost like a museum of a museum from years past.

Attracting Visitors

For years, the exhibits lay hidden behind the College of Physicians imposing walls and cast iron gates. Physicians from across the region flocked to the society to peruse the latest medical journals or borrow a specimen for analysis, but public visitors were few and far between and arranged only by appointment.

This situation began to change in the early 1990s, during the tenure of energetic museum director Gretchen Worden. In appearances on the Late Show with David Letterman and other national media, Worden brought the unique collections into the public consciousness. By the time of her death in 2004, the museum saw over 50,000 visitors a year.

This number than has since more than doubled under current director Robert Hicks. A place guaranteed to start conversations, the Mütter Museum has been called the most popular first-date spot in the city. Bride Magazine named it among the 50 best wedding venues in the nation. Many mornings, busloads of school kids wander the “disturbingly informative” exhibits,

But director Hicks hopes visitors experience it as more than just an array of weird objects. “I don’t want to be known as the oddity museum,” he says. “It’s a place where you can be curious in a public and safe way about how the body works.”

It’s a far cry from his original vision of a set of teaching tools, but the one-of-a-kind curiosities Mütter assembled so many years ago continue to stimulate and inform to this day. “It’s not the teaching tool Dr Mütter intended,” says George Wohlreich, MD, president of the College of Physicians. “But the museum still teaches us about ourselves: It shows us our common humanity.”

[Mütter Museum, 19 S. 22nd Street] muttermuseum.org.

A version of this article was previously published in the 2015/16 Where Philadelphia Guestbook

Aw, this was a really nice post. Taking the time and actual effort to generate a great article

DIsgusting. Those “people” people pay money to see and enter this perverted place, had a right to a proper burial, as well as the babies. Gross. Anything for money, right? For shame..