Thirty seven years ago, Bernard Havard was named president and producing artistic director to bring back to life America’s oldest continuously running theater, the Walnut Street Theatre. Together with his creative and administrative staff, Havard developed one of the most popular theaters on the East Coast. However, even the most successful theaters, especially those which take a risk with a play that might be difficult, can take a financial loss.

Few producers and directors would be willing to talk about these aspects of running a cultural institution. Havard admitted that for his production of Oscar Wilde’s A Woman of No Importance, “I’m not selling the number of tickets I hoped to sell.” In this interview, he described the risks he took and the efforts he and his team made to lead to one full house after another since Valentine’s Day.

Taking risks can lead to a financial loss for a theater

Henrik Eger: Recently, you took the risk of putting on the rarely performed A Woman of No Importance. What gave you the courage to produce and direct this wit-filled Oscar Wilde drama, which takes place in upper class Victorian England butdoes not come with the razzle-dazzle of My Fair Lady and other productions familiar to American audiences?

Bernard Havard: I enjoy Oscar Wilde’s work. I have great admiration for his writing, and I have great admiration for his courage. He was a man of great courage. Also, the play speaks to me about democratic values versus the British class system, which for me was always full of hypocrisy. But it has been a risk, and it continues to be a risk, because I’m not selling the number of tickets I hoped to sell.

Take the title: The Importance of Being Earnest is an extraordinarily well-known title, the most popular of his plays, but A Woman of No Importance is not as popular. It’s a more difficult play. He wrote the play in four acts, and the first three acts all take place at the large manor house, and they’re all full of Wildean wit and humor. But then, after Lord Illingworth attempts to kiss and seduce the young American lady, the Puritan, it becomes rather melodramatic, and it’s a tough change for the audience. It just is.

I think, possibly was influenced to some degree by Henrik Ibsen at that stage of his career. He was trying to mark out some new territory in terms of his playwriting. I find it an important transition, and I find it very moving, too. Some women I know weep with that scene, because they’re familiar with those relationships.

Henrik: For the role of a young American woman in search of an aristocratic husband, you took another risk by hiring a Temple sophomore. Tell us more about Audrey Ward and the difficult role of playing an independent American woman as seen through the eyes of Wilde in the early 1890s.

Bernard: I wanted it to be authentic, especially when Wilde describes this character as 18 years old. I held auditions for 35 young actresses, who had been screened by Rita, my assistant, and Audrey stood out in her audition as being able to command that role.

I’m less interested in academic training for actors and actresses. You either have the talent or you don’t. Talent is not something you can be taught. She has talent, and she took direction very well, which I guess she learned from her professors at Temple.

Connecting an old British play with a modern American audience

Henrik: What did you, your experienced actors, and your creative team do to present this satirical setup in such a way that American audiences would relate to it, especially as we are dealing with the barriers of linguistic class divisions in Victorian England?

Bernard: First of all, I made a number of substantive cuts to the text. I also allowed the actors to get involved in the cuts. During the rehearsal process, we probably reduced the play’s running time by about half an hour, and a lot of the references that we cut were references that were too obscure, or too English, or too unrelatable to an American experience. I didn’t see any point in keeping references that made no sense to a contemporary American audience.

However, I did supply one word to the text: when Karen Peakes as Mrs. Allonby mentions the place they’re talking about—Philadelphia. That was my one addition, and I thought it worked, because Wilde had been to Philadelphia. He knew about its Centennial International Exhibition. That’s what the young girl is actually reading about, so when the actress says, “that city with the funny name,” it was Philadelphia. It was a great laugh that American audiences could relate to.

Henrik: Strong British accents can present a problem for American audiences.

Bernard: All of the actors, I think more or less, gave me an English accent that was as close to being understood as you could get. I didn’t want any regional accents; I didn’t want any Yorkshire accents; I didn’t want any Cockneys. I was trying to get a clear English accent that was acceptable in terms of pronunciation. We worked very hard at pronunciation to make sure everybody was consistent.

When audience members complain about sound, something else might be going on

Henrik: Some people complained about sound, even though you have an excellent sound system. Like other theaters, the Walnut rents out hearing aids, free of charge, for anyone who requests a set before the show.

Bernard: A lot of it has to do with the accents. It’s an adjustment. Also, people, I don’t think, have the same kind of attention span that they had a few decades ago. It’s becoming more and more difficult.

Certainly Ian Merrill Peakes as Lord Illingworth knows how to project, and so does Mary Martello as Lady Caroline Pontefract. You have a company of actors who basically know how to project in a proscenium theater.

But it is an adjustment for an American to come in and hear a bunch of foreigners on that stage, people with foreign accents, anyway. And you have to adjust and listen.

The sound is heightened. There are a number of microphones on that stage. There are four small foot mics, and then there are mics in the vases and around the set to pick up the dialogue. Everything is amplified.

I just don’t like putting radio mics on actors for a classic piece like that. One of my bugbears is making sure the audience can’t see the microphone. If you see a microphone on an actor who’s performing in a classic piece, it takes me right out of it. Like, what the hell is that little thing on the forehead of that actor doing there? So I’m a bit old fashioned, I suppose, when it comes to hiring actors that can project.

Wilde at the Walnut: Valentine’s Day push, filling America’s oldest theater

Henrik: Earlier, you said that, unlike your other productions, A Woman of No Importance did not sell so well. What did you do to rectify this situation?

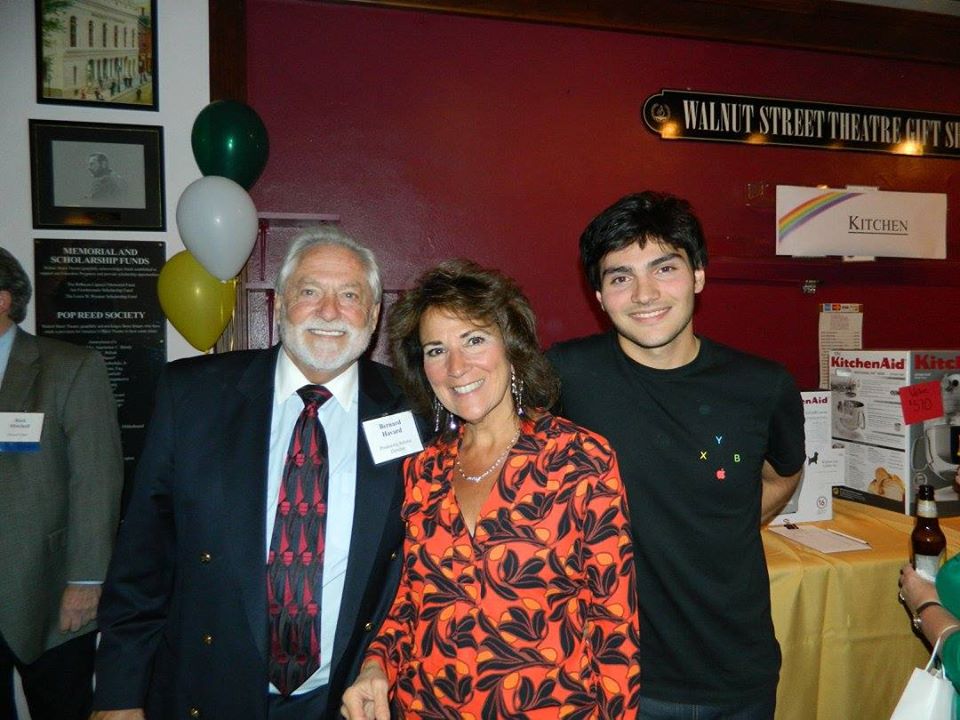

Bernard: We made a really large social media push for Valentine’s Day. We got my son, Brandon [O’Rourke who played Gerald Arbuthnot], involved and asked him to push it on his extensively subscribed social media platforms. Actually, he offered to do that. Contained in these social media posts was an ability to go to his bio to find the link to purchase tickets.

We attempted to get the rest of the cast involved by making production shots available to them. We offered special “two fer’s” and a $27 ticket for Valentine’s Day. All in all, we used Instagram, Facebook, and I believe some Twitter. We are also experimenting with texting.

Henrik: Impressive cooperation. What impact did this Valentine’s campaign have on ticket sales?

Bernard: It increased our attendance. We were probably selling close to 500 seats a performance, and this jacked it up to over 750 seats, so that’s something like a 50% increase. We now have a President’s Day special. Everyone is invited.

Henrik: Oscar Wilde’s wit and spirit will be hovering over the stage in every sold out performance, no doubt. And the unexpected ending of this play, which came as a shock in 1893, is delighting thousands of theatergoers.

[Walnut Street Theatre, 825 Walnut Street] January 14-March 1, 2020; walnutstreettheatre.org