Euripides wrote MEDEA in Greece around 2,450 years ago, and yet it is still being discussed and performed today, particularly the 1946 version, “freely adapted by Robinson Jeffers”—famous for his poetic epic style. Many times during this production, I could hear the 45th president of the U.S. like a threatening spirit in the back, as seen on stage by the attacks of Creon [John Lopes] and Jason [Jared Reed] on Medea’s “foreign” status and how that Greek xenophobia lead to fatal decisions, which eventually destroyed almost everyone involved in the process.

Against the original stones from the ruins of the 1840s grist-mill as the backdrop to this Greek tragedy at the Hedgerow Theatre, we experience not only a “marvelously despicable” Creon and Jason, but also the frighteningly tender and murderous Medea—played by Jennifer Summerfield, one of the stars of the Philadelphia theater scene.

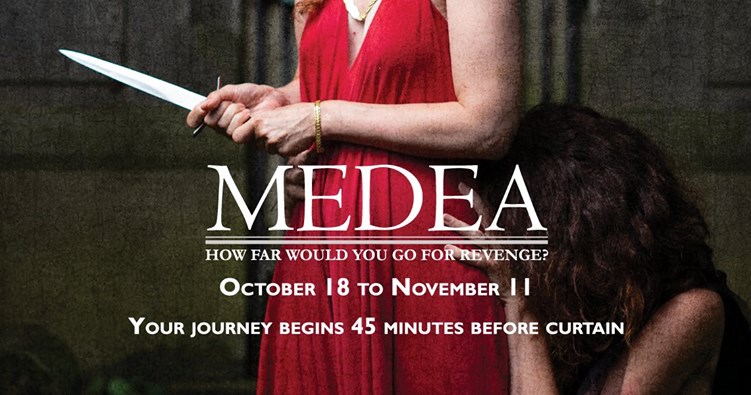

[Hedgerow Theatre, 64 Rose Valley Road, Rose Valley, PA] October 18-November 11, 2018; hedgerowtheatre.org

Henrik Eger: Why did the Hedgerow Theatre, famous for its many hilarious farces and the annual Shakespeare and Dickens’ Christmas Carol, choose this Greek tragedy and this translation in 2018?

Jennifer Summerfield: I am part of a three-season project Hedgerow has implemented, called the “Core-4 project,” where I and three other actors —Jared Reed [Hedgerow’s producing artistic director], Adam Altman, and Jessica DalCanton—perform in three shows a season. The nine-play series is geared toward our innate interests, personal goals, and development as performers.

Jared chose MEDEA, I think because he knew that I would always choose tragedy over comedy. I’m really only happy when it rains. I have to admit, however, that I felt pure terror when he put MEDEA forward as a Core-4 show. I don’t think it’s a play you ever think you’re ready for—not just because of the horrific subject matter, but because of its pedigree as the greatest Greek play written for a woman and the giants of the stage who have interpreted the role before you.

Originally, the production was slated for the autumn of 2019 and I thought, “Oh, okay. I have about two years to become a good enough actress. Maybe I can handle it.” However, I was shocked when we had to move it up a year—and I had only six months to fill those gargantuan shoes.

Jared, in his generosity, left the choice of translation completely up to me, and so I now have a bookshelf completely devoted to MEDEA translations and adaptations—some snappy and modern, others flowery and Victorian. The challenge, as I researched, was that Euripides’ original is incredibly spare in its language, but still has the poetic advantage of the original ancient Greek. I wanted to find a version that had a sense of modern immediacy, but also the beauty of a faraway time and place.

What really sold me on the Jeffers version, aside from the beautiful imagery and modern sensibility, was the development of the Nurse as a character and active force in Medea’s life. I knew that Jessica DalCanton, one of my favorite stage partners, could take the role and create something beautiful. The Jeffers version gives us an opportunity to have a deeper relationship on stage, with a shared history, stretching back to ancient Colchis.

Henrik: What aspects of your life as a woman did you bring to this production of MEDEA?

Jennifer: The structure of MEDEA lends itself perfectly to gender politics. Even if I hadn’t wanted to, it would have been impossible not to bring my experience as a woman to the table.

I hadn’t realized until we began to put the play together in the rehearsal room just how divided the men and women in MEDEA are. The action takes place in front of Medea’s house, which her husband Jason [who had divorced her and married Creon’s daughter] has deserted in order to marry the King of Corinth’s daughter. However, the Women of Corinth come to comfort her in her despair. Far from being the disengaged objective voices we often associate with the Greek chorus, these women [Minou Pourshariati, Julianne Schuab, and Susan Wefel] actively side with Medea against Jason and his self-interested betrayal of his family.

The men who come to confront Medea appear like potentially violent interlopers, breaching this enclave of women to explain away their actions and cast Medea as an hysterical, irrational woman who simply can’t see the wisdom of what the men have independently decided and done. Boy—when haven’t I felt like Medea in that sense?

Henrik: Given the complexity of this tragedy, what aspects of your life as an actor did you bring to bear to make your performance haunting and unforgettable?

Jennifer: When I was studying at The Neighborhood Playhouse [NYC], my modern dance teacher, Maher Benham, said it took 20 years to make an actor. That sounded depressing at the time, but 20 years later, I think I know what she meant. There are certain things that become built up in your “blood memory”—a collective experience that makes it possible not to actively think about every movement and inflection, because it’s part of your vocabulary.

I credit my teachers at the Playhouse for giving me the vocabulary, particularly Maher’s movement and Gary Ramsey’s vocal technique. Gary also once played us a recording of a scene from Judith Anderson’s production of MEDEA in the 1940s, and it gave me goosebumps that still return when I think about it today. Recently, I also played Marie Antoinette, directed by Brenna Geffers at Curio Theatre, who taught me incredibly difficult emotional shifts and sharp hairpin turns—skills I’m now using in MEDEA.

Henrik: Which are the most pivotal quotations from this tragedy that hit you the hardest?

Jennifer: At the first read-through, we collectively stopped and gave a sigh of recognition at the similarities we saw between Medea’s situation and the current immigration stance in our country now. The Chorus says of Creon, “I am of Corinth, and I say that Corinth is not well ruled. The city where even a woman, even a foreigner, suffers unjustly the rods of power is not well ruled.”

One line hits me harder and harder the longer I’m in the role: “I will not give up my little ones to the cold care of strangers. Hard faces, harsh hands. It would be far better for them to share my wandering ocean of beggary and bleak exile.”

Henrik: Tell us about the extraordinary path of a woman who was victimized but who also became a deadly angel of revenge and how you handled these constantly shifting personas.

Jennifer: Medea begins as a woman in crisis, recently abandoned by her husband who not only has married a younger, wealthier, more beautiful woman, but doesn’t even allow Medea an ounce of closure. He denies her the formality of a divorce because this “barbarian union” was never a true Greek marriage.

Medea has given all of her former power and agency to him, destroying every bridge they crossed to get to where they are now, making it impossible for her to seek comfort and refuge from her birth family and people. The only avenue she sees in her despair is to destroy everyone responsible for her unhappiness.

Henrik: Tell us about the director for this production.

Jennifer: It’s such a famous, baggage-laden play, that it was a challenge to let go of preconceptions. Megan Slater, our director, created a safe work environment where we could take chances and explore, even let go.

Megan helped me find the various colors and conflicting emotions within Medea’s character, including the complexity of her love and repulsion for the children she shares with Jason. The push and pull toward her children creates the greatest shifts in her emotions, right up to the final moment of the play, and adds to the suspense of the climax.

Henrik:How did your knowledge of what is happening in Washington, D.C. for the last two years, including its xenophobia and cruel treatment of refugee women and children, impact your performance?

Jennifer: The current news cycle definitely helped me as Medea [the “foreigner”] to personalize the interactions with Jason and Creon [the “Greeks”]. Their words about foreigners and power structure almost physically sting in their cruelty and immediacy and add fuel to the fire. It makes those moments of overwhelming anger and bursts of righteous indignation far more accessible.

Henrik: What was the most difficult part for you in tackling and solving this “creatively frightening project,” especially in a haunting scene that was only alluded to in classical Greece and not shown on stage—unlike the Hedgerow production?

Jennifer: It was about two weeks before the children were cast and began to work with us in the rehearsal room. I was terrified of having to look at them through Medea’s eyes, afraid they would be horrified by me and have nightmares. I didn’t know how to navigate that, never having worked on such an intense play with children before.

I needn’t have worried, however, because when Christopher and Andrea Muñoz auditioned for the roles, they knew the whole MEDEA myth and had practiced screaming at home. They’re amazing.

Henrik:What were some of the best parts for you in this production?

Jennifer: Megan Slater came on board with such enthusiasm and such clear ideas about the production and how to approach MEDEA that any fears I had about working on the role were immediately put to rest. She had assembled an amazing design team the first week and came in with great ideas on how to create a sense of dynamic action within the more descriptive passages so that there’s always a sense of forward movement. She also thought it was important that Medea have a real relationship with the Chorus women, and I love having that connection on stage.

Initially, I thought my only deep relationship as Medea would be with the Nurse, but Megan created some nuanced levels and tones by having the three women of the chorus develop three distinct personalities on stage.

John Lopes, a dear friend and lovely person, plays Creon with such odious pomposity that it was easy to hate him—something I would have thought would be impossible before this production. He’s marvelously despicable.

Henrik: Is there anything else you would like to share?

Jennifer: I am grateful to Hedgerow and Jared Reed for giving me a place to explore and grow. I first came to Hedgerow when I was a newly relocated teenager from Wyoming and took classes with Gay Carducci and the late Janet Kelsey. However, I never dreamed I’d play Medea on that beautiful stage. What a dream.

♦

45 minutes before each show, audiences are treated to Greek food and drinks. MEDEA runs through Nov. 11 at Hedgerow Theatre, 64 Rose Valley Road, Rose Valley, outside Media. 610-565-4211 or hedgerowtheatre.org

One Reply to “MEDEA, A Woman in Crisis: Interview with Jennifer Summerfield”