(Note: This is a series of reviews of art forms about which I know next to nothing as I step out of my professional comfort zone, theater. If you haven’t yet met D.A.L., take a look at other pieces in this series.)

Three years in the making, this $5 million project, and the work of sixteen conservators. the renovation of the Middle East Galleries at the Penn Museum is finally complete, and it opens to the public this weekend. A special feature of this new exhibition is the touchable reproductions.

The galleries are a treasure house of ancient artifacts, beautifully showcased and gently lit. And the fact that what was, several thousands of years ago, called Mesopotamia, is now called Iran and Iraq, inevitably gives one pause.

The theme of the exhibition is urbanism, a celebration of great cities and how ancient people changed their way of life in order to stay in one place all year round. And despite all the obvious differences between our city now and their city then, the show reveals the thread that is woven through our collective humanity.

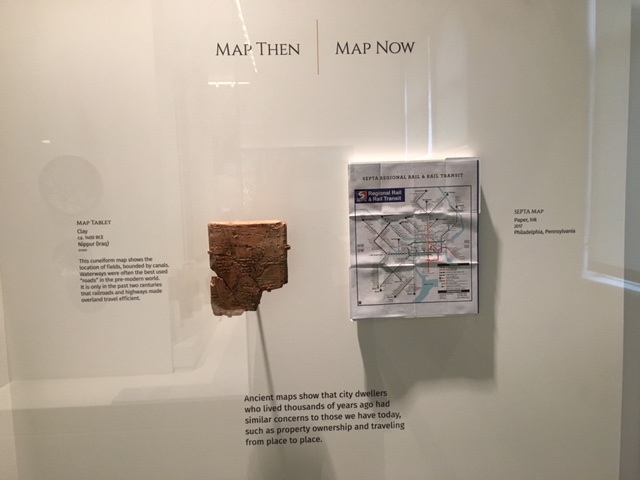

Perhaps the best illustrations of that thread are in two of the less spectacular display cases. One contains an ancient clay sewer pipe next to a bright green contemporary sewer pipe (purchased for the occasion from Lowes): they are the same length, same diameter and serve the same purpose. Nearby is another case displaying a map on a cuneiform clay tablet, and hung next to it is a SEPTA map of similar size and shape; like Philadelphia, Nippur was a city between two rivers, the Euphrates and the Tigris, and, as was always true, people have to get around, thus the need for maps. The difference, as Dan Rahimi, the Executive Director of the Galleries told me as he generously walked me through some of the rooms, is in the technology, not the need. (Not to mention the startling similarity between a hand-held tablet and a hand-held tablet!)

And Rahimi went on to say that, unlike other ancient cultures, the Greek and the Chinese, among examples, Mesopotamia died out, so the archeological finds are of a free-standing world. He gave me a glimpse into what must be the most fundamental thrill for an archaeologist when unearthing evidence of a lost world: “I hold a tool in my hand that hasn’t been held by another hand for 10,000 years.”

Besides these thought provoking proofs of our link to the past, there is the sheer beauty and, often, charm, of some of the objects on display:

*One of the most famous has traditionally been called “The Ram in the Thicket,” thought to reference the Abraham story in the Bible, but it is, actually, a just a goat munching on leaves on the lower branches of a tree. A photo of a contemporary goat in the same posture, rampant, front hooves on a low branch, munching on contemporary leaves, clinches it.

*The most opulent piece on display is the renowned “Puabi’s Burial Adornment”—precious beads and gold for the earrings, crown, belts—found in an enormous burial site where her many servants were bludgeoned to death to keep her company.

*The Akkadian/Sumerian poet Enheduanna (2285-2250 BCE) is the world’s first author who was known by name. She was a priestess who wrote psalms and you can see the tablets they are carved on. These are alongside the Gilgamesh tablets, recounting a chapter of that famous epic.

*There are the “Slipper Coffins,” corpse-sized ceramic containers, glazed and decorated; note the hole in one end: a rope was tied around the dead person’s ankles and he/she was pulled through; fragments of rope have been found on ankle bones.

And so it goes on: life and death, language and art. Penn Museum’s new galleries are a splendid testament to it all.