At the Academy Awards ceremony this Sunday, five nominees will compete for the award for Best Adapted Screenplay, a recognition given every year since the first Oscars in 1928. The nominated films are drawn from novels (Call Me by Your Name by André Aciman and Mudbound by Hillary Jordan), books and memoirs (The Disaster Artist by Greg Sestero and Tom Bissell and Molly’s Game by Molly Bloom), and comic books (Logan), but no plays.

That’s a far cry from the first award ceremony, when all three nominated films were drawn from theater (Glorious Betsy by Rida Johnson Young, and The Jazz Singer by Samson Raphaelson, and the winner Seventh Heaven by Austin Strong).

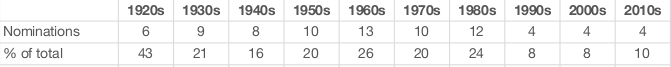

Here’s a look at the number of nominations for plays in the category of Best Adapted Screenplay across the decades .

From the earliest days of the Oscars through the 1980s, plays (and the occasional musical) consistently accounted for about a fifth to a quarter of all source works for the category. In 1951, four of the five movies nominated in the category were based on plays (Detective Story by Sidney Kingsley, Reigen by Arthur Schnitzler, A Streetcar Named Desire by Tennessee Williams, and the winner’s source An American Tragedy by Patrick Kearney).

The list of playwrights who saw their plays adapted into nominated movies reads like a who’s who of mid-century drama: Edward Albee, Jean Anouilh, Robert Bolt, Noel Coward, Lillian Hellman, Clifford Odets, Eugene O’Neill, Neil Simon. Tennessee Williams.

All these nominations produced several winners per decade: Philip Barry’s The Philadelphia Story inspired the category-winning film in 1940 (pipping The Long Voyage Home, based on short plays by Eugene O’Neill); Clifford Odet’s The Country Girl was the basis for the winning film in 1954, Robert Bolt adapted his own A Man for All Seasons to win the 1966 prize (beating out Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolfe).

After a barren decade (for wins) in the 1970s, the 1980s saw four plays used as the basis of award-winning films. But since Alfred Uhry adapted his own Driving Miss Daisy to win the 1989 prize, only twelve plays have been the source for nominations of Best Adapted Screenplay, with only eight nominated this millennium:

- 2002 Chicago by Bob Fosse and Fred Ebb

- 2004 The Man Who Was Peter Pan by Allan Knee

- 2008 Doubt: A Parable by John Patrick Shanley

- 2008 Frost/Nixon by Peter Morgan

- 2011 Farragut North by Beau Willimon

- 2012 Juicy and Delicious by Lucy Alibar

- 2016 Fences by August Wilson

- 2016 In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue by Tarell Alvin McCraney

Coincidentally, last year’s awards featured two nominees based on plays, both by African American playwrights. The award went to Moonlight, which is based on a play by Tarell Alvin McCraney. Even this award must be asterisked: McCraney is well-regarded as a playwright, particularly for his The Brothers Size, but his source play In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue, was an unpublished drama school project, never produced.

So why has no produced or published play has been the source for a Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar in almost thirty years?

This represents a larger trend of fewer plays being used as the source for films. Indeed, Broadway stages are more likely to see cookie-cutter musical adaptations of popular films than drama which warrants a cinematic interpretation.

One might point to theater’s diminishing role in our culture. Perhaps the relatively diminished talent pool of playwrights, as talented writers try their hand in other mediums.

Or is it a reflection of the movie industry. Maybe the rise of special effects sees less focus on traditional drama and dialog. Or perhaps film remains conservative, while theater tackles more avant-garde storytelling and dramatic techniques.

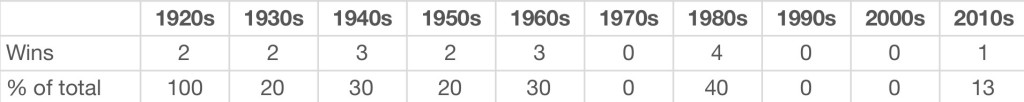

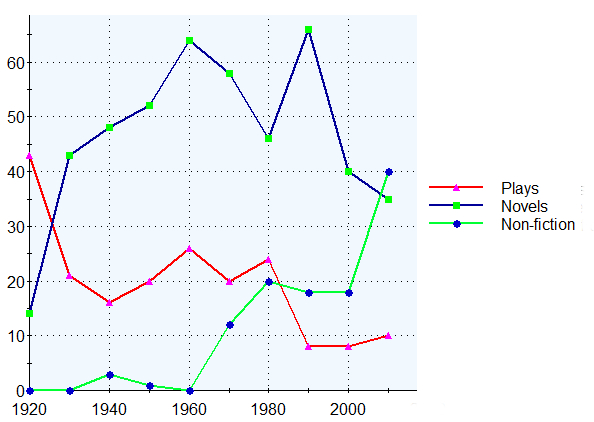

Recent years have seen more nominations for sequels (Toy Story 2 inspired by Toy Story, Before Midnight inspired by Before Sunrise), comics (American Splendor and X-Men), and television (Borat and The Thick of It). But the biggest source of for adaptations is now non-fiction works, including memoirs and autobiographies. Before Moonlight won in 2017, the last four award-winners were based on non-fiction works.

Novels once dominated as the source for Best Adapted Screenplay. yielding 32 of the 50 nominations in the 1960s, for example. None of the nominees were based on non-fiction works. The 1970s saw six nominees and three winners based on non-fiction, including The French Connection (1971) and All The President’s Men (1976). Since 2010, more nominees — and twice as many winners — have been based on non-fiction works than on novels.

Truth may not be stranger than fiction, but perhaps it’s proving more cinematic.

—