Luna Theater Company’s ANIMAL FARM, like George Orwell’s 1945 novella, begins with the death of Old Major (Michelle Pauls). The huge, beloved hog doesn’t go out quietly; he prefaces his demise with a speech, embittered by years of suffering, about the exploitation of animals by humans. Coughing and wheezing, he sketches a powerful dream of animal purity and egalitarianism.

What follows is an allegory of the Russian Revolution and Stalin’s real-life dystopia. The farm animals, after the death of Old Major, chase out the farmer. The pigs, rallying under a particularly swinish one named Napoleon (Tori Mittelman), quickly take control, using their superior intellect to twist ideals into power and cow the other animals into a new underclass.

What’s interesting about Old Major’s death scene, as directed by Gregory Scott Campbell, is that it acts as the introduction to the major defining convention of this play: people acting as animals.

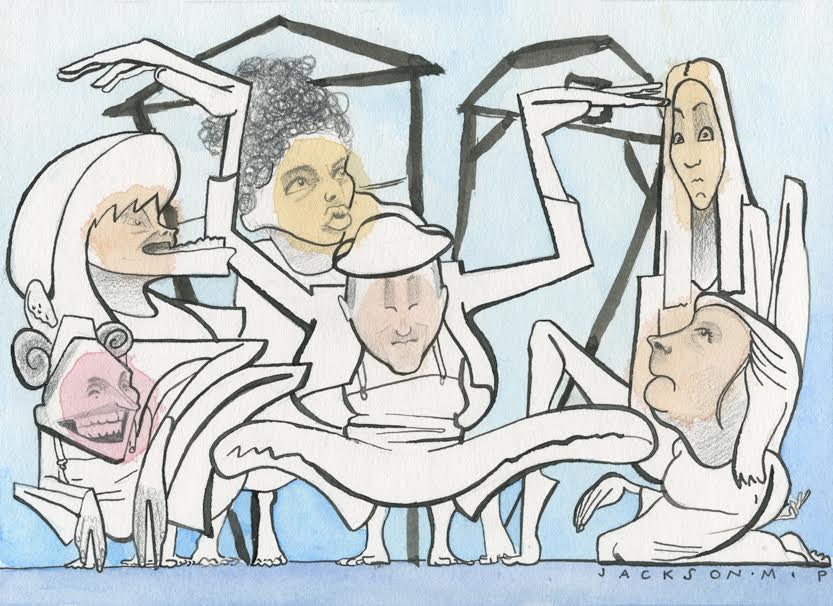

There is something more than incidental in the chosen physical realities for these animals, authored at least in part by choreographer/movement coach Peter Andrew Danzig. The pigs resemble human children, or trolls, rolling chaotically and joyfully around. The forked hands and toothy smiles, later, take on a demonic quality, specifically in Squealer (Michelle Pauls), a treacherous thug who might not be as clever as Napoleon, but is certainly the right combination of threatening and eager to rise by attrition.

The horses, meanwhile, are deprived of such human expressions. Bent at the hips, their eyes face mostly down, and their arms are raised to be parallel to the ground, fists clenched, representing their strong workers’ bodies.

Stances aren’t enough to tell this story, and the cast develops a fidgety rhythm, incidental movement and noise which could have become distracting if it wasn’t so precise and rich. The pigs roll around and scratch themselves. The horses in particular must express emotions and relationships through their bodies, voices, and incidental noises. A tensing arm, bared teeth, shifted weight: all of these have emotional repercussions.

We end up watching this instead of listening to Old Major, and not just because the movement well done. Though Major is excellently physically realized (her fingers, not cleft and pointy like the others, are twisted back into withered stumps, and her mouth seems palsied and warped, changing her voice), the speech is almost without character.

The language in Ian Wooldridge’s 2004 adaptation is true to the novel (at least in tone): stylized, dramatic, literary. At times it works, at times it doesn’t, and Old Major’s speech comes across like a history channel reenactment or a classroom lesson. The first twenty minutes of the play are weighed down by similar diatribes, and this, along with a few line flubs, work to confuse the early parts of the story and make characters feel unspecific. The pigs, for example, don’t take on separate identities until after Napoleon starts bumping people off.

This could be opening night jitters, because it’s all uphill from here, and the final 30 minutes or so are so excellently executed, culminating in the truly moving death of Boxer and a surprisingly creepy final scene, that you wish you had understood the ramp-up a little better.

After the revolution, the pigs’ story happens mostly in the wings. They enter intermittently, to hand down revised rules and orders, and Mittelman’s placid, smiling face in these instances acts as an obstinate shield against insight. She manages to generate fascination in Napoleon’s motives and machinations, showing just enough humanity (that is, pigness) to keep us wanting more.

Meanwhile, horses Boxer (Katherine Perry) and Clover (Kelly McCaughan) are constantly present. Perry brings what could easily be an inaccessibly sweet, idealistic, and patriotic workhorse to life, playing expertly with a world of personal tics and idiosyncrasies of voice.

The two of them move beyond the simple convention of “being” horses to the more complicated exploration of “interacting” as horses and expressing intimacy. Early on, when they bicker, they will speak in measured tones but with teeth bared and eyes wide. They look forward rather than into one another’s eyes. A moment of existential bewilderment is shared by resting their foreheads together. All of these add layers of richness to the animal physicality, which is truly the raison d’être of this play.

Campbell’s all-female production may not answer the question of why an allegory about Stalinism is relevant enough to stage, but it does answer the question of why to see another Luna show: an ambitious and subtly realized theatricality, balancing moving performances with a haunting denouement. [Luna Theater, 620 S. 8th Street] October 18-November 7, 2015; lunatheater.org.