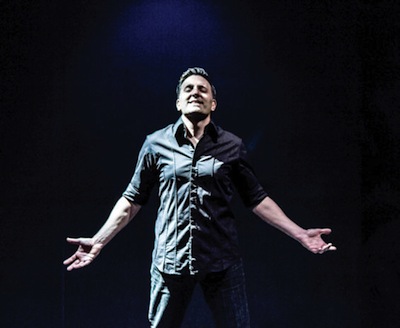

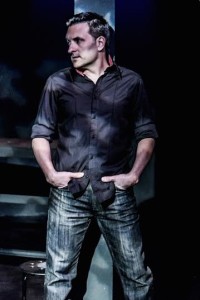

This year’s GayFest! launched with AT THE FLASH, an 80-minute, one-man show portraying five decades of modern gay history. David Leeper needs no costumes, no props, and no stage hands. Instead, he carries the weight of this moving and entertaining play by his chameleon-like transitions. With subtle facial expression and changing dialect—switching between male and female, Southern and Northern, white and black—Leeper uses the story of five disparate characters at one gay bar to trace a larger community story.

.

In the late 1960s, world-weary Rich is a married businessman with wife and kids. He lives the “American dream,” but doesn’t feel all his dreams have come true. Apprehensively, he tiptoes into a gay bar called The Flash (based on a real life Chicago bar which opened in 1965). A product of McCarthy-era conservatism, Rich denies his deep-seated desires and shuns the queer life. Will he regret his decision to step foot into The Flash?

While the 60s met with societal denial, the 70s saw quite a bit of romantic denial. In the least culturally impacting portrayal of Leeper’s performance, sassy drag queen Miss Sparkle recounts a relationship with a man who treated her like a real lady, showering her with gifts and attention. However, this affair wouldn’t last when he returned to his family without reciprocating her “I love you’s.” Though downcast in not finding someone who loves her for who she is on the inside, this hardship does not stop her confidence in her identity—powerfully bulldozing through life’s obstacles, calmly sashaying with class.

AIDS fostered torturous fear in the 80s. Fear hasn’t fazed Derrick though, as he lives life to the fullest at The Flash with the adventurous free spirit of Jack Kerouac and the devil-may-care angst of Holden Caulfield, suppressing the potential reality of his death sentence. Even with the energy of Madonna surging through his dancing limbs, his increasingly quaking body makes him worry that more than vivacity courses through his veins.

Mona Epstein epitomizes the flannel lesbian of the 90s as she brings her political activism for marriage equality to The Flash. Still an underrepresented demographic, the LGBT community is no longer hiding in the shadows as they were in the previous three generations. They are rising up. At this time (as Mona laments), 37% of the U.S. population support the legalization of gay marriage and 46% support gay couples to get adoption rights. To her chagrin, she fails to spark within her own community the same fiery passion she has for equality: “Sometimes people need to be pushed . . . to think.”

Derrick’s wild humor a decade before is juxtaposed with the melancholy of Mona’s story. She can’t be there for a loved one as the “family only” of a hospital prevents her from being at the bedside of her dying lover.

Even in this new millennium, when the LGBT community is widely accepted politically, overwhelmed bar owner Rod faces tension for not being accepted by his own family. Even as a husband, father of an adopted daughter, and an entrepreneur who has successfully reopened The Flash as a bar and restaurant, he still tries to prove to his father—who doesn’t think gay men will ever find success in business or in love—that he is just as successful as any heterosexual man.

While Leeper’s expressive acting clearly demarcates his characters, the five different narratives are harder to follow. After each character’s debut, the transitions have little rhythm, and the plot is incohesive at times. However, this structure also makes the performance delightfully unpredictable, leaving us hungry to know what will become of Derrick while currently spellbound by Leeper’s mastery of the sassy black Miss Sparkle.

But entertainment is not the only goal for AT THE FLASH. It seeks to edify both gay and non-gay audiences, to build a community of critical thinkers and empathizers who learn to engage with and love one another as human beings instead of playing God for sport. With a bigger picture in mind, this play goes beyond the dichotomy of gay and non-gay: it displays a message not of distinguished communities but of common human identity.

For someone like me, unfamiliar with the plight of the LGBT community, AT THE FLASH is eye opening. After having seen fifty years of LGBT history and life acted out before me, I felt connected to every character on stage and every human being squeezed into Plays and Players black box Skinner Studio. As I joined them in applause, I thought, “I didn’t know so much life could fit in such a tiny room.” [Plays & Players Skinner Studio, 1714 Delancey Street] August 7-9, 2015;quinceproductions.com.