Republished by kind permission from the FringeArts blog

“In film,” pronounced Ivo van Hove, director of Toneelgroep Amsterdam, the largest, and most culturally influential, theater in the Netherlands, “the director is the god of his creation.”

On June 28, I attended Live Remix, a daylong symposium on van Hove’s work and “the proliferation of live performances devised from film and digital media.” Curated by Tom Sellar, editor of Theater, and presented by FringeArts (and supported by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage), Live Remix opened with the screening of van Hove’s first and yet only feature film, Amsterdam (1997). The film acted as a precursor to a conversation with van Hove about his work and a round table with contemporary American artists whose work might speak to his. For those who came to hear van Hove talk about his adaptations of Ingmar Bergman films—like After the Rehearsal and Persona, which will be showing in the 2015 Fringe Festival—Amsterdam’s jarring aesthetic and gritty, violent characters are well outside expectations. Knowing little about van Hove myself, I expected a grey old man—more of a Sophocles than an Odysseus. But the man sitting across from Sellar is slim, matter of fact, and intense.

Knowing little about van Hove myself, I expected a grey old man—more of a Sophocles than an Odysseus. But the man sitting across from Sellar is slim, matter of fact, and intense.

Sellar directed van Hove onto his past, his youth devouring movies by John Cassavetes and Michelangelo Antonioni, and his turn to theater in his twenties—largely because film takes so long, he explained, and theater seemed a more realistic way to reach an audience. And how, late in his career, he began to adapt some of these films into stage plays.

“Bringing the movie to the stage is a challenge,” he pointed out. “It’s not meant to be on the stage.”

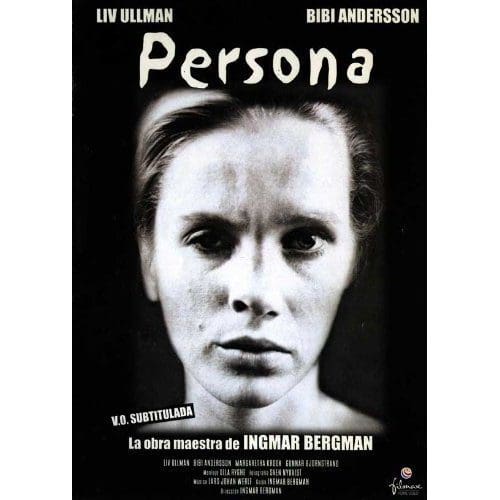

Persona lives in my mind in Bergman’s vibrant images—Liv Ullmann pulling back Bibi Andersson’s hair back to bare her forehead, both of them gazing languidly into us.

I, like many people, have never thought of Persona as a script. Its long stretches of silence or stillness make it a perfect leverage of the visual film medium against script. Persona, to me, is a film.

But something very simple that van Hove said made me, for the first time, remove images from script and consider it as a text. “In Persona,” he pointed out, “you get the sense that something in [Vogler’s] life is very wrong . . . something she has been covering up with her artistic life.”

The film had always led me to consider Bergman’s characters as a microcosm, as that picture of Ullman’s hand on Andersson’s head, or the slow smile on Andersson’s face while Ullman gives her interminable speech; not as individuals with individual problems, but as an encounter. Bergman’s strong, specific vision led me into one world to forget the possibilities of others.

“I always do an interpretation of the script, not the movie,” Van Hove says sharply. There is Bergman the writer, and Bergman the filmmaker. Van Hove’s appropriation of text suggests that there’s something the former had to say that the latter didn’t realize.

This conversation was followed by a panel discussion with three prominent New York artists: John Collins of Elevator Repair Service, Doris Mirescu of Dangerous Ground, and Ryan McNamara of Me3m Ballet. After showing five minute clips of their previous work, Sellar brought the conversation right around to the question of adaptation versus appropriation—is there a difference, and if so, what is it?

It’s a rhetorical question, impossible to answer in this forum. What it actually does is get the artists talking about their own practice of adaptation, and to how they use source material.

McNamara’s ME3M: a Story Ballet About the Internet, consisted of many isolated performances occurring at the same time in rooms and corridors of the Playboy theater in Miami. This was a work of adaptatin/appropriation, as well. At the start of the process, McNamara had his dancers each bring in a video from the internet that they responded to in some way.

They learned the moves in their piece, then began to create around them. “It wasn’t about replicating it. It was really about . . . making it disappear.”

This kind of appropriation of movement, visuals, and even text is not rare; it’s one that every artist in the round table uses as part of the process, and many others as well. “I’m not a choreographer,” says McNamara, “so I needed material.” Adding, “Every movement any body has ever done can be found on the internet.”

With regards to her own adaptations, Mirescu points out, “You have to learn to disrespect these films.”

Van Hove’s Amsterdam, the movie that started the evening, had its own perspective on appropriation.

It has the convoluted, supercharged plot of a Hollywood crime flick, but charming characters are hard to find. Cliché dialogue is heated up with ugliness: desperate, childish, and selfish. Even the soundtrack, with cheesy indie pop tunes and amped club music, borrows from Hollywood’s stock, but van Hove uses music strategically, twisting the expected emotional tone of scenes, and connecting moments, through the extension of a song, which otherwise would feel disparate.

The swirling stories and scheming crooks create a halo around an unlikely hero, Khaleed the car thief, a young, swaggering thug who escaped the family business in Fez for the shining gem of Europe that Amsterdam seemed to be. With all legal economies closed to him, he takes what seems the only choice open to him: to adapt to a life of crime, of theft, of appropriation.

—Julius Ferraro

After the Rehearsal / Persona

Written by Ingmar Bergman

Directed by Ivo van Hove

Toneelgroep Amsterdam (Netherlands)

Showtimes:

Sept 3 at 8pm

Sept 4 at 8pm

Sept 5 at 8pm

23rd Street Armory

22 South 23rd Street

Wheelchair accessible