Wilma’s HAMLET opens slow and spooky on the battlements, where haze, gloom and dark are shot through with brilliant shafts of light. There’s strange music and the sound of amplified breathing hints of Darth Vader. A good deal of time is taken to establish the atmosphere of anxiety and fear.

Zainab Jah, an African-born British woman, plays Hamlet. Founding artistic director Blanka Zizka, who was invested in this actor for the role, wrote in her program notes, “I knew I wouldn’t even attempt to direct the play without her.” Wilma’s advertising appears to be as much about showcasing the actor as it is about telling the Hamlet story. This brings to mind the critical reception of Sarah Bernhardt’s performances as Hamlet at the turn of the 20th century: the shows seem to have been all about Bernhardt. In the program Zizka notes, “Hamlet is not going to change gender because he’s played by a woman.” However, Hamlet is not an un-gendered character, and a diminutive female Hamlet does alter the physical dynamic.

HAMLET, not unlike the U.S. Constitution, endures partly because there are holes in it. Its imperfections and spaces allow for different ways to read it: It’s a choice. Dramaturg and literary manager Walter Bilderback, who aided the artistic director with investigation and had a key role in the extensive editing job, says, “I think we have found a political and psychological thriller at the heart of Hamlet.” While this conclusion is just one among equal choices, and some cuts to the script have resulted in missing information, I admire the energy and spirit of his exploration. If I were a theater director I’d want a Bilderback to have my back.

Coming as she did from Cold War Eastern Europe, Zizka’s deep interest in matters political informs her work. I wonder if in her youth she may have been influenced by Jan Kott, the brilliant Polish theorist and critic who discerned brutal politics in HAMLET, seeing him as a young political rebel. Peter Brook noted that Kott “assumes without question that every one of his readers will at some point have been woken by police in the middle of the night.”

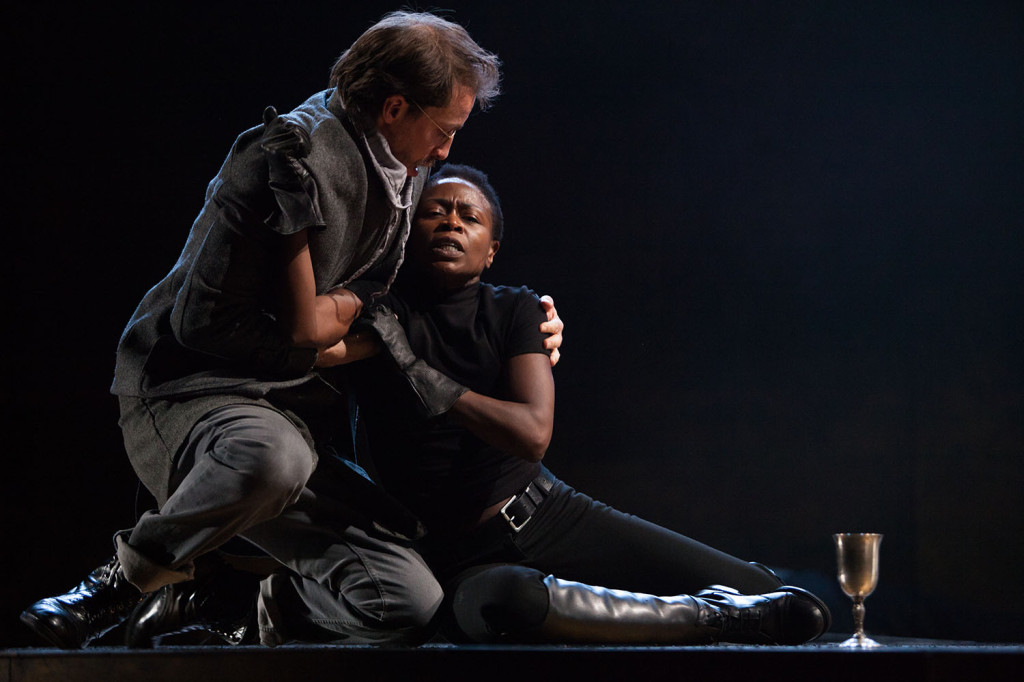

The experience of watching this show is like watching an ensemble performance in which virtually each actor performs alone. Like a necklace with the links removed—each jewel shines separately, some brilliantly. Hamlet is pragmatic, not dreamy and introspective as usual, and he takes himself very seriously. The role is quite physical, and although Jah rarely speaks loudly, she sometimes seems hoarse, as if she were having trouble sustaining her breath. But her remarkable stage presence carries her, as Hamlet negotiates characters who live on different levels of abstraction and almost seem to inhabit different productions.

Scenes featuring the royals can be stylized and formal, while scenes with Ophelia (Sarah Gliko) are exaggerated and angular. Roles played more naturally are Horatio (Ross Beschler), Laertes (Brian Ratcliffe), and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (Keith Conallen and Jered McLenigan, respectively). Ed Swidey’s simple and honest delivery as the First Player and Lindsay Smiling’s loose, appealing approach to the Gravedigger damn near steal the show.

Steven Rishard, well attuned to his Claudius role, shines in the confession scene as a villain uncomfortable with honesty. Guilt wipes the villainous smile off his face. Krista Apple-Hodge, attired in a fabulous dress with orange-lined cape and an eccentric hairdo that’s just the thing, delivers a glittering and brittle Gertrude. Where some actors will wink at the role, Joe Guzmán plays his Polonius straight. Shakespeare isn’t kind to Polonius. Like TWELFTH NIGHT’s foolish Malvolio he’s the butt of Shakespeare’s pomposity jokes. I always feel sorry for these two characters.

With the unusually jocular handling of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, there’s a tinge of feed-forward to Wilma’s upcoming production of Stoppard’s ROSENCRANTZ AND GUILDENSTERN ARE DEAD. (An aim behind pairing these plays was to feature the actors in their same roles. It’s unfortunate that NY-based Jah will not be staying to play the supporting Hamlet role.)

The anti-naturalistic idea of distancing characters is congruent with the created stage environment. However, choosing style over substance has characters reciting and posturing. At times Hamlet’s responses give the impression of being motivated more by directorial concept than by anything organic. And when characters don’t connect, an important theatrical question remains unanswered: “Why do people do what they do?” Contact is what makes interactions compelling. If, by design, actors must keep their distance or look away from each other, or break into stylized movement and set-speeches, then important connective tissue between them is excised. This is an understandable directorial choice in a closed world where Hamlet can’t trust anyone but Horatio. Still, scenes can be robbed of richness and depth. For instance, in Gertrude’s chamber words are declaimed and action is dramatically posed as if for separate photo ops. It’s not hard to get why Hamlet puts on madness and distances himself in order to live long enough to overthrow the criminal king. But the high degree of distancing in the performance also negates Hamlet’s entire relationship with Ophelia. He may be hiding his love because they are being watched, but because there’s no hint of it left, his too-late protestation of love at her funeral does not ring true.

An unusual flash of fire exhibited in the usually playful recorder scene looks misplaced at first blush. In this punning scene with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, a teasing “mad” Hamlet typically makes his serious point lightly, letting them know he’s got their number, “S’blood, do you think I am easier to be played on than a pipe?” But here it’s played not with delicious nuance, but with furious anger. The handling of the scene makes more sense when you see it as one of the director’s flashpoints where Hamlet’s purpose briefly surfaces.

Top notch designers contribute much to the show’s dramatically different feel, with their grand scale set design and street art, distinctive lighting, costumes, sound design and strikingly original music. The political theme comes through most obviously in the set design. Glowing, golden and metallic, the insular world of Elsinore Castle is surrounded by grit, politically-tinged graffiti, and gloomy graphic visual art. From time to time a load of soot falls down onto the stage, perhaps denoting a decaying society? Or rotting royalty responsible for grey urban blight?

Yet, while the production design brings politics to the fore, clear political opportunities are not taken, and in fact are cut. One example: In the playscript when Laertes rushes home from France after his father’s murder, he comes armed for a fight. An angry crowd outside the castle backs him, calling for him to be king. But in this version when Laertes arrives on the scene after his father’s demise, only to discover that his sister is also dead, he’s just a poor lone guy. Without the backing of an angry mob behind him, he has come unstuck from the greater flow of the story (although Claudius will still use him). But when such a sure chance to give voice to the hinted at popular unrest is not taken, a political thread is abandoned, and the shaky political climate suggested by the set design pretty much becomes moot.

Zizka’s daring theatrical idealism consistently challenges conventional modes of production, this time with a HAMLET that features arresting visuals, solid performances, and stunning swordplay, yet keeps its distance as it amazes but doesn’t warm. [The Wilma Theater, 265 S. Broad Street]. March 25-May 2, 2015; wilmatheater.org.

- Read an interview with Zainab Jah about her role as Hamlet

- Read a feature on the Wilma’s pairing of HAMLET with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead.