One of the most shameful aspects in modern US history took place during World War II, when large numbers of Japanese-American citizens of all ages, including babies, were forced to leave everything behind and move into internment camps. Traumatized, many Japanese-Americans didn’t dare to talk about the subject for decades. One of the few exceptions was Gordon Hirabayashi (1918-2012), a young pacifist and student who defied the order and took the case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. He lost the case in 1944 and was sent to jail.

Many decades later, in 1987, Hirabayashi’s convictions were overturned, because evidence showed that the Supreme Court arguments had been based on “rumored incidents” of non-existent Japanese American sabotage, instead of facts. In 2011, the Acting Solicitor General officially confessed error in that regard. In May 2012, President Obama awarded Gordon Hirabayashi posthumously the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honor.

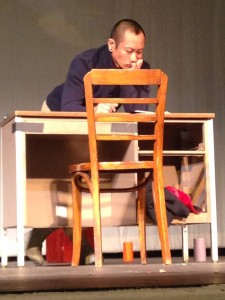

Jeanne Sakata, a well-known Japanese-American actor, met and interviewed Gordon Hirabayashi, and spent years in writing and fine-tuning HOLD THESE TRUTHS, a creative docudrama in form of a one-man show about the life of the courageous yet unassuming young hero of the Japanese-American community. HOLD THESE TRUTHS is being performed all over the United States and now premieres at Plays and Players, running February 13 through March 1, 2015. [Read the Phindie review.]

Henrik Eger: Which experiences of your childhood and adolescence influenced your career choices the most?

Jeanne Sakata: I loved to read when I was a kid, and I always had my nose buried in a book. One Christmas, I remember that someone gave me a children’s adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women—I think I was in second grade—and I just buried myself in that book and fell in love with Jo and wanted to grow up and be a writer.

So it’s nice that that’s actually happened, finally. I never seriously entertained the idea of being an actor until college. I was an English Literature major when suddenly I fell in love with many of the performing arts—singing, dance, storytelling, puppetry, acting. I started taking classes in all of them, and then realized that the theater was a place where I could make use of all these things I loved, as well as immerse myself in great dramatic literature.

Japanese-American Relationships

Eger: When you grew up as a young person of Japanese-American descent, did you experience any negative attitudes—either personally or through what you read or heard through the media?

Sakata: I grew up in a small farming town just south of the Bay Area, but it had a large and prominent Japanese American [JA] community, so I didn’t experience overtly negative attitudes on a daily basis, but of course I noticed that there weren’t a lot of faces that looked like mine in the media—on TV, in the movies, or in magazines. I certainly was aware that there were racist people out there in the world, though, and that my family had experienced that racial hostility in the past, but I didn’t know the specifics till later in life.

Eger: Was there a defining moment when you first strongly identified with the plight of Japanese-Americans?

Sakata: I had a wonderful Asian American Studies professor at UCLA, Yuji Ichioka [1936–2002, American historian and civil rights activist who coined the term “Asian American” to replace the widely used derogatory term “Oriental”]. He was an exciting, fiery, passionate mentor. Yuji’s class was definitely a seminal moment for me in terms of really digging into my family’s history, and by extension, the history of Japanese Americans, as he assigned us to write a personal history of a Japanese American and set it against the larger backdrop of Japanese American history.

I chose to write about my paternal grandfather, Harry Kyusaburo Sakata, and I’ll always be grateful to Yuji for that assignment, because that was the beginning of my full realization of what had happened to my family and the JA community during WWII. Also, there was a huge Asian American student movement that was happening in the 60’s and 70’s, and that served to educate me as well.

Eger: When you initially heard about the internment camps in the US during WWII, what was your response?

Sakata: As I grew up, I learned that my family on my father’s side had been in the Poston, Arizona camp during WWII, but my father, aunts and uncles never talked about the camp experience. I’m sure because they were too traumatized by it and just wanted to bury the past as best they could. As I started to learn the details of the forced removal during my college years, of course, I was angered and shocked over what had happened, as well as very sad.

Eger: What were the most shocking, but also the most moving discoveries you made about the plight of Japanese-Americans being forced to live in internment camps during WWII?

Sakata: The most shocking thing I learned was that the US government demanded that even babies in orphanages who were of Japanese ancestry be sent to the barbed wire camps, and that included babies who were of mixed blood. That still takes my breath away.

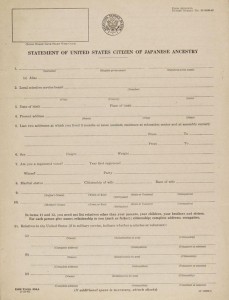

Eger: As a result of the “Loyalty Questionnaire,” the Japanese-American community split into two opposing groups—“loyal” and “disloyal”—during and after WWII. One side cooperated with the American government, renouncing all ties with Japan and fighting as American soldiers. The other side refused to renounce their Japanese heritage and refused to fight in the U.S. Army. “No-no status was stigmatized after the war, and many have remained reluctant to tell their stories,” according to the Densho Encyclopedia. Is it true that only Japanese-Americans who refused to give up their Japanese loyalty were interned, or did all Japanese-Americans located on the West Coast live under the threat of internment during WWII?

Sakata: The orders were that anyone of Japanese ancestry who lived in designated Military Zones on the West Coast—including the Nisei [Japanese-language term for second-generation children born to Japanese people in the new country], who were American citizens—had to leave their homes and be imprisoned in the camps, including the elderly, the feeble and sick, and as I said before, even babies in orphanages. In Washington state, where a great deal of Hold These Truths takes place, the orders were that anyone with 1/16th Japanese blood had to go.

Eger: Gordon Hirabayashi, the central figure in your play, was treated as a second-class citizen—as were most other Japanese-Americans during WWII. It took decades before his actions as a resister and human rights activist were recognized and validated. How were your family members and their friends treated during WWII?

Sakata: Since my father’s side of the family were all living on the West Coast in California, my father, my grandparents, my aunts, uncles and a couple of older cousins all had to suddenly leave their schools and jobs and go live behind barbed wire in Poston, Arizona. My mother’s side of the family lived in Colorado, and so did not have to go through that tragedy, but they nevertheless experienced plenty of racism where they lived.

Gordon Hirabayashi: Japanese-American internment history

Eger: Describe the steps you took to research Hirabayashi, the hero of the Japanese-American internment history.

Sakata: In the 1990’s, I saw a wonderful PBS documentary, made by John de Graaf, called A Personal Matter: Hirabayashi vs. The United States, where I first learned about Gordon’s story, and was just enthralled and fascinated. I was determined to contact Gordon and meet him somehow, and as luck would have it, I got Gordon’s phone number from a young student who had just interviewed him in Seattle for a paper she was writing, so I called him up and told him I would love to meet him and try to write a solo play about him, and would he consent to a series of interviews?

He was very gracious and welcoming, even when I told him I had never written a play before. He invited me to interview him at his brother Ed’s place in Glen Ellen, California, where he was going to be visiting. Then we did another round of interviews in Edmonton [Alberta, Canada], where he was living with his wife Susan. And of course, I read everything I could get my hands on about Gordon, and watched other videos that mentioned his case.

Eger: Hirabayashi acted as an exceptionally mature young person with a great belief in the American Constitution and human rights. He became one of three Japanese-Americans to openly defy internment, writing on his draft registration card: “I am a conscientious objector.” He was convicted to serve time behind bars. As the government refused to pay for his transportation, he actually hitchhiked to the prison in Arizona. Given the pressure on Japanese-Americans during WWII, what do you think gave him the ability to defy the most powerful decision makers in the US, even at a young age?

Sakata: Gordon always attributed a lot of this to his parents, who were role models for him in that they had already bucked tradition in many ways by belonging to the Mukyokai, a small Japanese religious sect, founded by Uchimura Kanzo, that was pacifistic, democratic, and non-denominational. They were very much like the Quakers, in that they had no religious hierarchies to speak of, no pastor, no “traditional” church setting.

They had their worship services in their living rooms, just sitting together and waiting for the Spirit to move someone to speak or offer up a prayer or passage. That practice would have been very unusual for Christian Japanese Americans of that time, since most of them belonged to the big established churches like the Methodists and Presbyterians. Also, Gordon’s mother was a brilliant and fiery spirit who was elected Vice President of the local Japanese Association and for a woman to have that position was almost unheard of. So Gordon always said that his unusual parents and upbringing provided some “icebreakers” that ultimately influenced his own actions during WWII.

Eger: What struck you the most about him as a person?

Sakata: Gordon had a tremendous sense of adventure, an enormous appetite for life, and an insatiable curiosity, zest for travel, ideas, and learning. He had a wonderful light within him, too, a kind of spiritual warmth that you could feel even when you were on the phone with him. He had a keen and incisive intellect, and a marvelous sense of humor and irony. And he was a great storyteller! You sensed that he had an iron will, which, of course, figures into HOLD THESE TRUTHS.

Development of HOLD THESE TRUTHS

Eger: Becoming a successful actor all over the US is a tremendous achievement. However, to conduct research and interviews demands specialized skills. Few theater artists manage to make the transition from acting to writing. You did. Tell us about the hurdles you had to overcome in the process of writing your first fact-based play.

Sakata: Since HOLD THESE TRUTHS was my first attempt at writing a play, I made a lot of attempts at a first draft that ultimately landed in the wastebasket! It was a tremendous challenge to distill all the historical facts of the play and weave them into the personal narrative of Gordon’s story. And since I was also pursuing an acting career while I was trying to become a writer, it was a real challenge to juggle the two. I couldn’t write very well when I was acting, so I’d put the writing aside when I got an acting job. And then, when I returned to the project, it took a while to get back into the world of the play. And I really didn’t know how to be a playwright in terms of the business side of things.

However, I was incredibly lucky to have wonderful mentors who helped me along the way, because they believed so much in the play, like Len and Zak Berkman, Morgan Jenness, Chay Yew, Jessica Kubzansky, and countless others who read the script, gave me invaluable feedback, and helped me shape the play. The same is true for organizations like the Epic Theatre Ensemble, Lark Play Development Center, New York Theatre Workshop, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Asian American Theatre Festival, Center Theatre Group, and the Antaeus Company, who hosted readings or workshopped the play, which led to our world premiere at East West Players in 2007 and all the productions that happened after that.

Eger: During your extensive research and writing phases, how did the sacrifices you made in terms of time and engagement impact your personal life?

Sakata: I don’t really feel it was a sacrifice! Though it was very difficult to write a play for the first time, especially a historical one, and though it was incredibly hard work, the story was such a thrilling one, and one that I was so passionate about, that the hours would just fly by. It was really a labor of love, and I remember feeling incredibly alive when I was working on it. And because of my family’s history in the camps, the whole process felt deeply healing and redemptive.

Eger: When writing your play, you dealt with literally hundreds of different documents and information from interviews—a huge task. What criteria did you use to cut it down to the size of the play that is now being performed all over the country?

Sakata: This is where a terrific mentor steps in and helps you, if you’re lucky! I had this huge 3 ½ hour rough draft and had no idea how to shape it. One of my mentors, Len Berkman [professor of theater at Smith College], suggested I put two words up on my refrigerator: “Gordon’s actions.” He said that if what was on the page reflected Gordon being active and driving his story forward in a dynamic way, that’s what I should keep. And if that wasn’t happening, I should look for cuts in those parts. And that was just incredible advice, and once I understood, I started whittling away and began to see the play emerge.

Eger: Did all the organizations and individuals that you contacted support your work, or were there some closed doors?

Sakata: As with any written work, you get rejections, and I certainly got my share when I was trying to shop the play around. However, I was incredibly lucky in that once we had our premiere with East West Players, and with each production after that, there was always someone who came up to me or contacted me and said, “I loved the play and I want to recommend this play to so-and-so,” or “I want to help bring it to my city.” And that’s how the journey of the play has been—people bringing it to their theaters and communities, largely on the strength of word of mouth.

Eger: Jeanne Sakata, it’s an honor to welcome you and Gordon Hirabayashi to Philadelphia with Makoto Hirano reliving the life of one of the finest Japanese-Americans in US history. Many thanks. Dōmo arigatō.