She has been a crucial part of some of your favorite productions, but you’ve never seen Katherine Fritz onstage..A regular costume designer in Philadelphia, she won a 2014 Critic’s Award from Phindie for her work on Mary Stuart. She is the only non-actor member of the Philadelphia Artists Collective, which produced that show. You can see Katherine’s work this month in Quintessence Theatre’s production of Kafka’s THE METAMORPHOSIS. She’s also a popular writer, posts from her blogs I Am Begging My Mother Not to Read This Blog and LadyPockets have “gone viral” and have been republished on Huffington Post. Phindie talked to Katherine about her work, writing, cockroaches, and hanging out in yoga pants.

Phindie: How did you get into costume design?

Katherine Fritz: To be honest, I got into it when I discovered I was a lousy actor! I was involved in theatre in high school—performed in a bunch of crappy musicals—and auditioned for a few shows in college kind of on a whim, but found myself cast in a ton of projects. I discovered pretty early on that I didn’t actually like the work of being an actor—I felt exposed and fraudulent and didn’t enjoy the feeling of being onstage as much as I had remembered. But I was also buying my clothes in thrift shops and hacking them apart kind of as a fun side project, and that snowballed into the discovery that I loved the process of creating characters through clothing and attire.

Phindie: What’s the designer’s role in a production? When do you enter the conversation and how much do you work with the director and actors to craft your vision?

KF: I think my role in any production is to create the visual world of the play, and that is going to be an intense collaborative effort between director, other designers, and the actors. I try to bring visual research and ideas into the conversation early on with the director. I also think that involving actors in the process is vital. It always shocks me when I hear from actors that they sometimes attend costume fittings where their ideas are met with resistance or frustration from the designers—the truth is that designers can’t sit in the room, and haven’t undergone the process of crafting character from the same place as the actors, and often the actors have incredible ideas that I love accommodating and incorporating whenever possible. If I can provide a costume that an actor feels comfortable in, that will allow the actor to do their best work. I think communication is so key to doing what I do.

Phindie: How did you get involved with Quintessence’s production of KAFKA’S THE METAMORPHOSIS? Have you worked with the company before?

KF: No, actually. I’ve worked with Becky on several other projects—our first collaboration was Applied Mechanic’s “Vainglorious,” this sprawling historical fantasia based on the lives of Napoleon, Josephine, and Beethoven. I had 26 actors and a miniscule budget, but I was working alongside the brilliant Maria Shaplin to create this integrated world—we wound up buying tons of stuff from thrift shops in a very limited color palate, dying and distressing and hacking apart contemporary clothes to make them feel like worn, ghostly representations of historical attire. It’s some of my favorite work that I’ve ever made. Becky is actually the first outside director that Quintessence has hired, and I am the first outside designer, so that’s an amazing opportunity that I was excited to be a part of. I love working with people who I already speak some kind of shorthand with—I trust that Becky has amazing and specific ideas about how to create her world, and she’s always on board to try whatever weirdness springs from my brain to see if it might work. What’s great about Becky is that she responds really well to visual cues that might not be strictly literal. Working with her feels like stepping into an amazingly friendly and familiar test lab, where we’re gonna try a bunch of crazy ideas and see what sticks.

Phindie: Were you familiar with the source material? Where else did you draw inspiration?

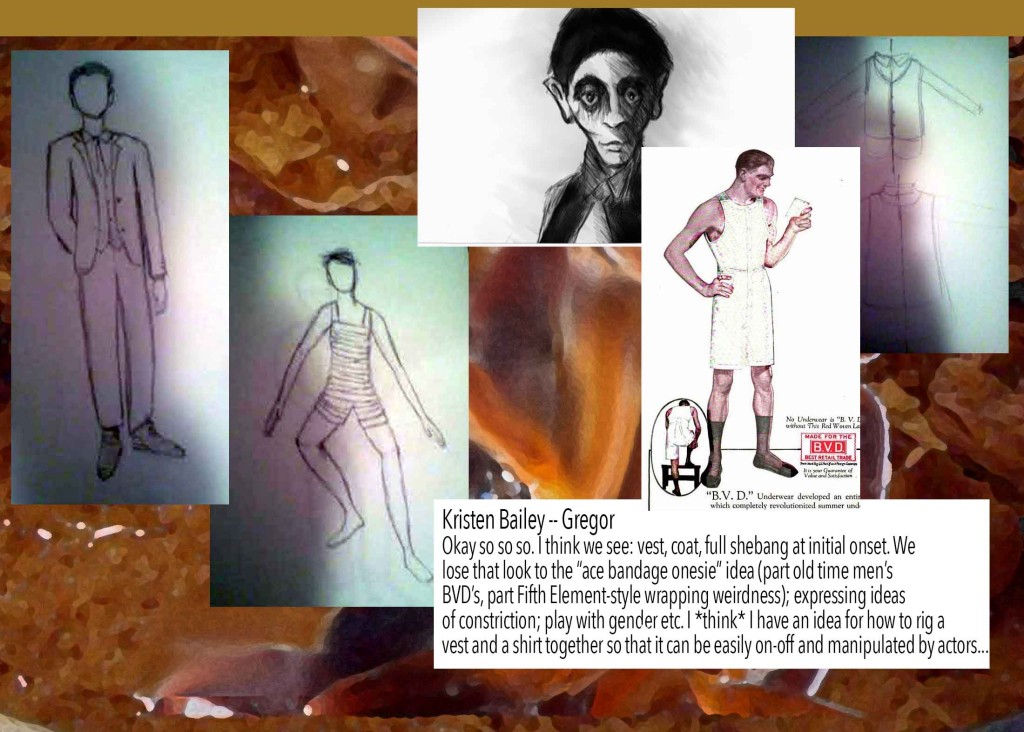

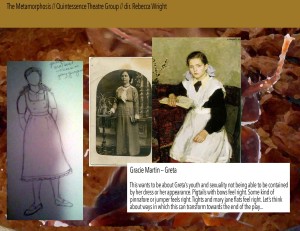

KF: I read Kafka’s short story in college, and re-read it before beginning the design process. I drew a lot of inspiration from period photos of the time—these gorgeous sepia-toned old photographs—that reminded me of the color palate of the cockroach. Our palate wants to feel like those golden browns and tans and yellows, icky bug colors that have their own specific, muted vibrancy. There was a dance piece several years ago based on the Kafka story, and while their world looks nothing like ours, we loved this idea that as the dance progressed, the white, spare stage became coated in this disgusting bug-gut messy substance. We’re playing with the idea of a bug-like slime that can emerge from costume pieces as Gregor’s transformation evolves.

Phindie: This seems like something of a dream project for a costume designer, what are the unique challenges and opportunities?

KF: I love that we’ve cast Kristen Bailey to play Gregor, and I think the gender-bent casting is my favorite element to play around with. Taking the masculinity out of that character and affirming the overall metaphor — Gregor as “everyman,” or “every person”—playing with that androgyny is super-fun, and I love tackling that challenge. Kristen is game for everything, and she’s an incredibly physical performer, so my challenge is going to involve creating period garments that have some magic tricks to them — clothes that can stretch and move to accommodate her physical performance, yet still evoke this sensation of restriction that seems essential to understanding the time period and the theme of the story. The rest of the cast shifts between specific characters and these “bug-like” formations, this physical ensemble storytelling — my challenge is to create specific character looks that still allow them to blend together when needed. Doug Hara, who is playing the Father—I mean, I’m so in awe of that guy, he’s this incredibly expressive and dynamic performer who uses his body in amazing and unexpected ways when he’s building a character—I am so excited to find the items that will allow him to transform physically and still allow him to blend into the ensemble when needed.

Phindie: In some ways, is it that much harder when the script calls for characters dressed in “normal” modern attire? How do you go about crafting costume for those productions?

KF: I mean, I do a ton of contemporary work, and I love it—but it comes with its own set of challenges. Sometimes people don’t see that as a “real design” because it’s about shopping in mainstream stores, and not about building garments or doing historical research or sourcing vintage pieces—but there’s sometimes even more effort involved with modern shows because everyone gets dressed in the morning, everyone knows what contemporary attire looks like, you know? So everybody has an opinion. What’s great about contemporary projects is that when a piece isn’t working, you just go back to the store and try again—versus a period show, when you have to do a bit more creative problem-solving in order to change a garment.

Phindie: A couple years after I began reviewing plays, I met a costume designer at a Fringe Arts Scratch Night. After talking to her, I went back and looked through all my reviews and not one of them mentioned the costumes. I’m more attentive now, but does it annoy you that people can overlook this crucial aspect of every play?

KF: Eh. To be honest, it used to bother me—but that was before I realized how much more love I got in a public forum than some of my harder-working peers. It bothers me a lot more that props designers aren’t eligible for any awards, or that there’s no forum to publicly recognize stage managers — what those folks do is so much more comprehensive, and often requires a special combination of technical wizardry and immense patience that I can’t even imagine. When costumes are mentioned in a review, it’s usually one of two things: either the design is so spectacularly awesome that it stands out (so: “Vainglorious” got a lot of love, as did the PAC’s production of “Mary Stuart”—I find this happens more frequently with period shows) or the design is so spectacularly bad that it distracts from the storytelling altogether! I design a lot of contemporary work, and because everyone is familiar with contemporary clothing, it doesn’t usually get mentioned. But that’s like complaining that the Oscars tend to reward dramas and biopics and ignore comedies … you know? True, and a little annoying, but there’s bigger fish to fry.

Phindie: You’ve mentored some high school and college costume designers. What do you see as the essential qualities for the job?

KF: I LOVE my students, and I love mentoring young designers. I think honesty is always the best policy — I’m going to have a different process and method than other designers will, and I think you can learn from me what you can learn from me, and then you have to find your own systems and methods. I’m not some guru who knows how this should all be done—I’m just this one person who has found her own way of doing things, and you can take that and build from it to find your own way. I think experimentation is critical, and I try to encourage that—I don’t know that there’s one “right way” to design costumes or to create renderings or to build a concept with a director. Each project is going to have its own particular alchemy, and I like to remind my students that it’s a collaborative process. It’s not about the designer, ultimately. It’s about the final product, none of which is possible without the immense number of people working on the project each contributing in their own way. The designer’s role is to find where they fit inside that process, to build upon others’ ideas, to contribute their own suggestions, to not get hurt or offended when something doesn’t work, to support an overall vision.

Phindie: You’re also a hugely popular blogger. What do you like about that creative outlet?

KF: This sounds incredibly cliché, but—man, my life changed in so many unexpected ways when my blog went viral. My life just straight-up changed, for the better. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I think there was a part of design that was unsatisfying to me in a way that I can articulate better now. My role as designer is to create in collaboration, and I think I needed a place where I could create something and release it into the world on my own, with just my artistic ownership attached. It’s opened up literally the entire world for me, and having a space where I can share thoughts and ideas and frustrations, where I can open up a dialogue or make a persuasive argument—I mean, that’s incredible. I feel very lucky and blessed to have received so much attention, to have a dedicated following of people who want to hear what I have to say.

I love it. I didn’t think I was a writer before I started that blog; now I do. It’s a part of me that I can’t believe I didn’t know existed, and now that I know it is there, it feels like a critical part of my identity as a human and as an artist.

I am still posting on both I Am Begging My Mother Not To Read This Blog and Ladypockets; I’m working on my first book, which is another whole thing. That’s such a different process—it’s slow, there are setbacks, I get frustrated, it moves glacially, I question myself a lot. It’s hard, I beat myself up that it doesn’t move faster. But I go back to it every day. And you do that for love. I hope that in the months and years to come, that I will be able to strike more of a balance — sometimes I really struggle with toggling between a very busy design career and simply needing more hours in the day to bang away at my laptop.

Having the blog has made me a happier person. I am a much happier person with this creative outlet. I love being a writer. That I can say, for sure.

Phindie: What’s your favorite outfit?

KF: Yoga pants, cashmere sweater, pearl earrings, fuzzy slippers. What? Isn’t everybody’s?

Phindie: Erhm, mine’s a little different, but yes. Thanks Katherine!

Find out more about Katherine and her work at katherinefritz.com.

Quintessence Theatre Group presents Franz Kafka’s THE METAMORPHOSIS [Sedgwick Theatre, 7137 Germantown Avenue, Mount Airy] February 4-March 1, 2015; quintessencetheatre.org.

- Read an interview with costume designer Katherine Fritz on designing for THE METAMORPHOSIS

- Susan Bernofsky writes in the New Yorker about translating Kafka‘s book

- Henrik Eger interviews director Rebecca Wright