Philadelphia’s oldest theater is also by far it’s most popular and financially secure. In a time when other large theaters are struggling to stay afloat (cf, Philadelphia Theater Company and the Prince Theater), the Walnut Street Theatre maintains the largest subscriber base in the country. In the first section three-part series, Katelyn Behrman sits down with Walnut artistic director Bernard Havard and other local theater folk to consider the playhouse’s commitment to popular entertainment.

“I got to be careful about this, because um—” Jim Schlatter, a professional actor and a professor of the theater arts at the University of Pennsylvania, pauses. He releases a short, raspy breath and leans back in his office chair. His arms stretch back behind him before softly settling, once more, on the cluttered desk in front of him. “—Because, definition: running your own theater is like an insane occupation. So, it’s not even fair to say that Bernard Havard is safe in his choices, because he’s got to maintain a huge subscription base; he’s got to have quality productions. It’s a big theater. So, I don’t want to say safe.” His right hand reaches up to his chin, almost anxiously stroking his snow-white beard, as he quickly spills out his reasoning: “But, he’s got to maintain a very large subscription audience; his audience knows what they want and what they expect, so he’s got to give it to them.”

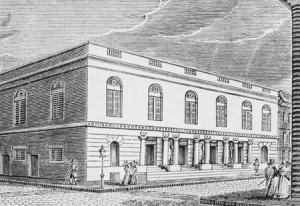

Boasting 56,000 annual subscribers, the Walnut Street Theatre is the most subscribed to theater company in the world. The sand-colored building on the corner of Ninth and Walnut streets hosts the official state theater of Pennsylvania and America’s oldest theater.

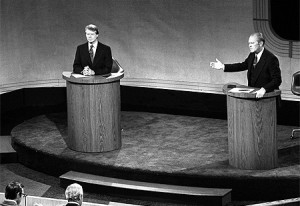

On February 2, 1809, the Walnut opened its doors as an equestrian act–based circus. Three years later, the Walnut dismantled the big top, leaving the tricks of the animals and the shrieks of the crowd to the two other Philadelphia circuses. Thomas Jefferson and the Marquis de Lafayette attended the Walnut’s first theatrical production, The Rivals: the dirt ring that horses’ hooves trampled over was transformed into a stage. In the next two centuries, such famous actors as Audrey Hepburn and Marlon Brando, and renowned politicians including Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford, graced this stage, earning the theater its title as a national historic landmark.

By 1982, however, the Walnut had strayed from the mission written on its playbills in the 1800s: to produce theater that appealed to the “vox populi,” or voice of the people. Instead of producing its own shows, the Walnut struggled to rent out space to other performing arts groups. The board knew that it needed to make a change, and so they approached Bernard Havard, director of the Atlanta Alliance Theater, to be the general manager.

“He turned it down,” remembers Tom Quinn, the theater’s director of education. His light blue eyes widen, and he perches forward on the small, round table. “Havard said, ‘The only thing that would make me take the job is if you turn it into a producing house, because a theater without original plays has no heart.’”

The board worried about the expense of turning the Walnut into a producing house, as the theater already had incurred a great deal of debt and producing shows in-house would cost millions of dollars. But, Quinn notes, “Bernard was so persuasive, they figured they would take a shot at it and try it. So, he was hired in 1982 to turn us into a producing house.”

“A producing house,” explains Havard, in his quintessentially proper British accent, “is the difference between buying a cake off the shelf or baking it yourself with all of the ingredients.” He adjusts himself in his plush, burgundy chair, looks around his spacious office, and spreads his hands across the mahogany, oval conference table. “A producing theater company produces all of the ingredients. You’re building all the scenery, the props, the costumes. You’re hiring the directors, the actors, and so you build it from the ground up, as opposed to buying it off the shelf.” The gamble to convert the non-profit rental facility into a self-producing, non-profit regional theater paid off, as within two years, the Walnut had earned a surplus of revenue. Today, the Walnut Street Theater Company produces shows ranging from summer musicals like Grease to intimate stories such as Beautiful Boy and to classic kids’ shows like A Christmas Carol. Almost every performance plays to a full house.

A few steps away from the Walnut’s lobby, Quinn opens the door to a room overflowing with theater posters from the past thirty-one years. He scans the posters from left to right, explaining, “Everything goes in order: you can sort of see when the theater started doing better because of how colorful the posters get.” Simple black and white posters cover the top left-hand corner of the room, while electrifying, boldly colored posters extend across the right wall. Even though he’s been in the room several times, Quinn’s eyes still flicker across the walls in wonder as he reads aloud some of the poster titles: “Fiddler on the Roof, Hairspray…Bernard chooses the titles himself based off of what he thinks our subscribers are going to see, and that’s made some interesting choices over the years,” Quinn explains, gazing around the room.

Dressed in a houndstooth jacket and petite rectangular glasses, Bernard Havard taps on the oval table in his office, describing his choice of plays: “I have to consider our fifty six thousand subscribers, here, which is the largest subscription audience in the world: I have to consider what they will tolerate and what they will enjoy. So, that’s the first consideration.”

Harvard’s adherence to his audience’s desires meant Shakespeare was dropped from the Walnut’s repertoire. “Bernard’s a huge devotee of Shakespeare,” explains Quinn; “It’s a lot of his background. He actually trained with the Royal National Theater’s Laurence Olivier. When he came to the Walnut, he told the board at the time that every year we’re going to produce one Shakespearean production.” Quinn scans the posters and points to the Shakespearean ones: Taming of the Shrew, A Midsummers Night’s Dream, and As You Like It. He sighs, “And that might be about it. We stopped doing Shakespeare, because he recognized that the Shakespearean shows had a 40% attendance rate as opposed to the musicals, which were selling out.”

“From a marketing standpoint, Shakespeare became a very dangerous situation for us,” explains Havard. “If you have a large subscription audience, and they’re buying five plays and you’re discounting to a point where they’re getting basically two productions virtually for free as part of the package; if they don’t like two of those five, there is no advantage financially for them to subscribe. They’ll just pick and choose the ones they want.” Havard shakes his head, chuckling to himself, “Now, if the foundations here had written to our rescue and had given me a significant amount of extra income, I would have been very pleased to continue to do Shakespeare.”

Foundation and government support contributes just thirteen percent of the Walnut’s total income ($15.8 million in 2011: see a Phindie feature on theater income). In comparison, most Philadelphia theaters run on fifty percent earned and fifty percent contributed income. “So, the amount of risk that I can take is fairly limited,” concludes Havard.

However, theater journalist (and Phindie editor) Christopher Munden believes that the theater may now be able to assume the risk of incorporating Shakespeare into its repertoire. Munden grew up following the Royal Shakespeare Company, making him a big fan of the Bard from an early age.Sipping a cup of coffee from Good Karma Café, Munden pushes his glasses to the top of his nose and considers Havard’s decision to cut Shakespeare. “It’s not shocking,” he slowly utters in a slight British accent. “For what he’s trying to do, that was the right decision for him. I wouldn’t be surprised if the Walnut could now throw in a few Shakespeares every couple of years, but why break what’s working?”

A 56,000-strong subscriber base testifies that the Walnut’s popular programming is working.

According to Havard, the theater strives to provide entertainment that anyone—not just those who have a background in theater—can enjoy. “Anytime the theater has not followed a populist point of view,” he explains, knocking dramatically on the table, “It. Has. Failed. We’ve got over 200 years of history here, and you can chart the scale of progression on a graph over the two centuries. And you can see that every time that some elitist got a hold of this theater and decided to push an elitist program and point of view, this theater failed.” Havard takes a deep breath, “We’ve got a track record!”

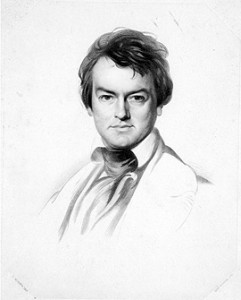

Ironically, Havard sees the theater’s populist roots in actor Edwin Forrest’s interpretation of Shakespeare. Forrest made his debut at the Walnut at just age fourteen on November 27, 1829. The program for that evening, a production of Douglas; Or, the Noble Shepherd, humbly listed Forrest as a “Young Gentleman of this City.” Soon, however, Forrest’s name was splashed across the center of the Walnut’s posters as the young actor gained fame.

Havard meanders over to his office wall and points out a picture of Forrest playing Macbeth. He jokes, “Macbeth is of course not supposed to be mentioned in the theater, so I should go outside, turn around three times and spit.” Havard stays standing and continues. “What was significant about Edwin Forrest and his history here and the American theater was that he was a popular man of the people. He didn’t speak with an English plummy accent like I do. He was a man of the people and he came in direct conflict with the English style of acting, like that of William Macready.”

Both Macready and Forrest performed in Shakespeare plays, but their interpretations differed. Forrest leaned more towards a populist, forceful style of acting, while Macready tilted towards an elitist, subdued style. As Havard explains, Macready belonged to the group of “hoity-toity, so-called English people who thought, you know, that Shakespeare should be done with a plummy English accent. And those two views—Forrest’s popular take and Macready’s elitist take—clashed.”

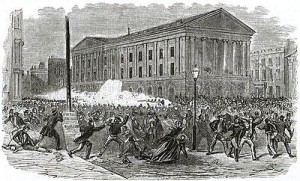

Havard elaborates that the divide between the popular acting of Forrest and the elite acting of Macready resulted in huge riots. “They were called the Astor Place riots and twenty-six people were killed, which brings into perspective how important the theater was in the 18th and 19th centuries in America and how polarized the elitists were against the popular people.”

On May 10, 1849, Forrest’s supporters, “primarily the Irish immigrants who had become Americans,” notes Havard, invaded Macready’s performance of Macbeth at New York’s Astor Place Theater. Forrest’s supporters soon became out of hand, causing the state militia to open fire and for Macready to flee, never to appear in an American theater again. Forrest, and his popular view of the theater, had won.

Even before learning about Forrest’s influence on the Walnut, Havard had begun to question his elitist notions. “I’d swallowed it hook, line, and sinker; I was an absolute elitist,” he admits. One summer he was working at the Rainbow Stage in Winnipeg, Canada. “You can see the picture on the wall there,” he says pointing toward a photo of an outdoor amphitheater. “The theater seated 3,000 people and they came because they wanted to be entertained. They didn’t come so that they could wear fancy clothes. They didn’t come because of some social rationale behind going there or because their friends were part of it. They were looking for a night’s entertainment and a good night out, and that became the defining moment for me.”

Havard steps away from the photograph and places himself back in the lush chair. His voice rises a few pitches, and he concludes, “I saw that people were really coming to the theater because they wanted to, not because they felt any sort of social or educational obligation to do so.” Fittingly, Havard’s feeling at the Rainbow Stage parallels the one that Forrest must have had while performing for the people at the Walnut. “Having learned about our history and certainly Mr. Edwin Forrest,” reflects Harvard, “we follow in his direction, which is a popular direction.”

Today, a full-length statue of Edwin Forrest in the role of Shakespeare’s Coriolanus, a popular hero, stands in the lobby of the Walnut to commemorate his influence on the theater. Forrest, in a nod of respect, raises his chin towards the stage. Quinn paces around the statue, admiring its marbled sheen and says, “In his will, he actually wrote in his will, that on his birthday and the Fourth of July that the Edwin Forrest Society, a foundation which he created back in the 1870s, would come together to toast him and have a drink. So twice a year, the Edwin Forrest Society gathers here, and they walk over to Franklin Square, where he’s buried, and they toast him still to this day. It’s kind of a cool tradition that still exists. That he’s had this legacy.”

Read part 2 and part 3 of Katelyn Behrman’s feature on the Walnut Street Theatre.

Beautifully written