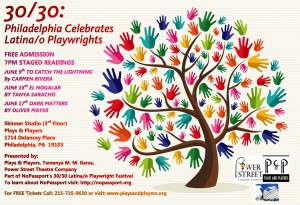

Plays & Players and Power Street Theater Company are continuing their collaborative effort to bring new plays by Latino playwrights to the stage. The three plays presented this month were chosen during the 30/30 event held in March, part of NoPassport’s nationwide effort to focus on Latino theater. (Find out more about this national program, launched by NoPassport founder Caridad Svich with Dominic D’Andrea, here.) Phindie talked with series co-producer Tamanya Garza, a longtime leader of the Philadelphia Latino theater community and director of El Nogalar (June 16), the second reading in the three-play series. (Other dates: To Catch the Lightning, June 9, and Dark Matters, June 17)

Phindie: How did you get involved with the 30/30 series?

Tamanya Garza: I was asked by the lovely Maura Krause to participate as a speaker on a Philadelphia New Play Initiative (PNPI) panel discussion about self-producing plays in Philadelphia. There I met two of the very dynamic women behind Power Street Theatre Company, Gabriela Sanchez and Erlina Ortiz. During the panel someone asked how to engage Latino theatergoers, and I answered very honestly and I think my answer really resonated with them. So, they approached me after the discussion about working together along with Daniel Student, the producing artistic director of Plays & Players. A beautiful friendship was born.

Phindie: Why do you think this series is necessary?

TG: I think 30/30/1, the Philadelphia incarnation of NoPassport’s international 30/30 festival to celebrate Latino playwrights, is a really engaging way to create excitement about all of the Latino playwrights that make this country their home. We are so lucky we have so, so many incredible perspectives and intriguing voices here. But often most of them remain silenced by lack of productions/residencies/fellowships at major regional and Broadway theaters.

It’s a bit like this article I read recently on HowlRound.com. Author Tlaloc Rivas talks about how critics in Atlanta refused to review a play he directed, probably because it was in Spanish, and how their decision can have lasting and detrimental consequences to his career as a tenure-tracked professor. It’s called the “not quite right” syndrome. The way theaters often decide playwrights and artists of color are “not quite right” for a position or production—a very insidious way to ensure our art remains homogeneous even if our audiences do not. And, though the decision is not always a conscious one, it means that often artists of color and their stories are severely marginalized and rarely have the exposure of art that fits more neatly within the historical canon. In Tloloc Rivas’ words: “I want Latina/o theater to be acknowledged and vital to the fabric of the American theater.”

Also, by pairing the introduction of 30 Latino plays with a panel discussion and staged reading series, as we have and are doing, we not only have a chance to examine many of the questions you asked in this interview but we were also to showcase the talents of Latino actors and directors.

Phindie: Tell me a little about El Nogalar by Tanya Saracho.

TG: El Nogalar (The Pecan Orchard) is a play rooted in the upheaval that is currently occurring in Mexico and along the Mexican-American border due to the choke hold drug cartels have on many communities. It is also a glorious adaptation of Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, dealing with the themes of a changing nation where social class is rapidly decaying and becoming something new.

Phindie: What attracted you to the piece?

TG: Many, many different elements. The poetry of survival. How people do so many things—often unimaginable things—to survive when their way of life is being threatened. The complicated dynamics of a Mexican family. How pride, fear, joy and hope act differently on matriarchal cultures. Saracho’s examination of both American and Mexican societies and how children of immigrants often feel like they belong to, and are wanted by, neither. Finally, it explores how the people we decide to love can shape our entire lives.

Because of the work my parents did, I grew up all over the world. But I was born El Paso, Texas, which sits right across the border from Cuidad Juarez. Long before the work of the drug cartels made the news for the brutality it exacts upon Mexico now, that violence made a home on the streets of these twin cities. So some of my first memories growing up are of the cultural clashes that Saracho talks about.

Because of the work my parents did, I grew up all over the world. But I was born El Paso, Texas, which sits right across the border from Cuidad Juarez. Long before the work of the drug cartels made the news for the brutality it exacts upon Mexico now, that violence made a home on the streets of these twin cities. So some of my first memories growing up are of the cultural clashes that Saracho talks about.

I remember not being able to play in my front yard because kidnapping and human trafficking of Mexican-American children was so prevalent. I remember the scores of women, the ones now referred to as the Women of Juarez, who crossed into the US to work at garment factories and babysitters in the homes of the rich. These women were tortured, raped and buried in shallow graves in the desert without their hands or heads. I remember that these crimes created a cultural conundrum because the Americans wouldn’t investigate the incidents because they weren’t American citizens and the Mexicans wouldn’t either because they didn’t have jurisdiction. I remember feeling hunted. Like I could never quite breathe. Saracho captures this terror so gorgeously, as well as the mundane activities – going to school, going to church, going to the grocery store – that still have to find a way to continue within it.

Phindie: I don’t see many Latina/o actors on Philly stages. Is this a case of under-representation or a lack of active artists?

TG: That’s a great question and one we spent a good amount of time addressing in the original panel discussion. I think it is easy for people to assume that there aren’t that many Latina/o actors in Philadelphia, but it is very untrue. We have such a diverse population in Philadelphia and so many schools with amazing theater programs—Temple, UArts, UPenn, Villanova, Drexel, Arcadia—that are training lots of new artists of color. But if you look at the plays that are being produced, and how they are being cast, there is definitely a problem with representation of our very vibrant culture onstage.

Even in plays about Latina/o characters, often the focus is on getting someone that “looks Latino” not someone who has a Latina/o background or can even convincingly speak Spanish onstage. The Philadelphia theater community has started a really important discussion about how to effectively and respectfully present a culture onstage and we, as a community, are quickly realizing that we still have a long way to go. But I am so excited that we are having the discussion and there are many, many people who are willing to give input about how to make future productions much more inclusive of the cultures they hope to highlight. But no, there is no shortage of Latina/o actors, as evidenced by how many are participating in our event as panelists, readers or actors.

Phindie: What unique obstacles do Latina/o actors and directors face in Philadelphia theater? How about playwrights?

TG: I think Latina/o actors, directors and playwrights face many of the same obstacles that other artists of color face: The fact that any time an actor of color is placed in role that isn’t specifically written for a person of color it is considered “non-traditional casting” which stigmatizes the action from the beginning; the fact that casting actors of different races as love interests is still considered salacious by some; the fact that we are expected to always be cognizant of our ethnicity and focus on “Latino” topics in our work even though our interests are as varied as everyone else’s which makes any topic we find important a “Latino” topic; the fact that arts programs have been eliminated in many heavily minority schools and how this lack of exposure has impacted artists and audiences for years.

In the panel discussion one of the questions we posed was “Do you think labeling a play Latino will help or hurt ticket sales.” And the answer was that it is complicated. While many artists want to express pride in their heritage, they find that once a play is labeled Latino by a theater it is marketed differently, it is reviewed differently, the expectations for audiences are different—using a cultural label is a very political action.The label can be used to create space between the artists, theaters, and audiences, and I want to get to a place where it creates intrigue instead. I want the work artists of color do to be considered as just as important as our heritage and how we represent it.

Finally, in our panel we addressed the topic of mentorship. I have had so many really powerful mentors who took an interest in me and my work early on and who provided me the tools and opportunities to succeed at this level. We need more mentors who have faced some of the same challenges that young artists are facing now and more formalized programs to forge those relationships. We also need more people who are invested in seeing these young artists succeed in casting offices, on boards, in the director’s chair, as a part of the non-profit funding model. Change happens from within, and the panelists believe that we have to take personal responsibility for making it happen.

Phindie: What changes, if any, have you seen in this regard since you’ve been involved in Philadelphia theater?

TG: In the words of Quiara Alegría Hudes from the 30/30/1 opening remarks (read here), “So what exactly is a Latino playwright?… Is she a grateful guest at someone else’s table? Or is she a carpenter building a new damn table from scratch?”

One of the most encouraging developments is seeing Latina/o and non-Latino artists alike create ways for their voices to be heard without waiting to be invited to do so. NoPassport’s 30/30 festival is one example. So is the riveting work of playwrights like James Ijames, already a very successful actor, who crafts the stories he wants to see onstage himself, like The Threshing Floor. The founding of organizations like PlayPenn, The Foundry, Directors Gathering, and PNPI that democratize the production process by making education and networking so accessible and enthralling. The breathing into existence of new companies like Power Street Theatre Company that is ” an ensemble-based theater company composed of socially-conscious theater artists collaborating to create new work that explores social issues.” We want to be a catalyst for cultural outreach and understanding within Philadelphia and beyond. ” Lastly, the existence of organizations like Taller Puertorriqueño whose members seek to close the cultural and arts education gap that affects so many children in our city.

What I love about these projects is that they all have an outreach component. Artists don’t just want to get their voices heard, they want to create spaces for other members of the community to be able to so do as well. Amirite?

Phindie: There seems to be a steady flow of Latino playwrights. Quiara Alegría Hudes is a Philadelphia Latina playwright come good. Kristoffer Diaz and Octavio Solis have both been acclaimed recently. Who else are you excited about?

TG: I can’t wait to see what Power Street Theatre Company produces for the Fringe. Erlina Ortiz, one of the members of Power Street, is directing quite a bit this summer, so I really want to know more about how she brings herself to her work as an individual. I’m excited about J. C. Lee of Pookie Goes Grenading fame, Philip Dawkins, who wrote Failure: A Love Story, and Kim Rosenstock who wrote the very recently closed Tigers Be Still, all of whom I met through my work as Azuka Theatre’s president of the board of directors. I always want to know what Jackie Goldfinger is writing next because I have never met a playwright like her in my life. I’m intrigued by what questions are on Quinn D. Eli’s mind because he approaches really big, meaty topics like race, identity and love with so much intelligence and grace. I have loved Jordan Harrison, Sarah Ruhl, Carolyn Gage and Genne Murphy for years and wish Genne still lived in Philly as she did for so many years. And for the record I would read absolutely anything dramaturg and Chair of the Department of Drama at Washington College (my alma mater) Michele Volansky put in my hand because she is just.that.good.

Some of the playwrights whose works I was privileged to read while working on 30/30—Tanya Saracho, Oliver Mayer, Alejandro Morales, Carmen Pelaez, Enrique Urueta—really lit a fire inside of me because I saw so much of myself in their very different plays, and yet the themes were so amazingly universal. And of course I can’t wait to see what NoPassport, Caridad Svich, and Dominic D’Andrea do to follow up the 30/30 festival. It will just have to be incredible.

Phindie: Do many Latinos go to the theater in Philadelphia?

TG: In my experience not nearly enough.

Phindie: Why do you think that is?

TG: I think once we figure out the representation and arts education pieces that will be much less of an issue. In the meantime though, if theaters want to have a relationship with the Latino community they have to make an effort to create one. Theaters have to ask themselves how to engage Latina/os, what stories they want to hear, where and how to market to them, and how to create new theatergoers.

My parents, who exposed me to every kind of art imaginable as a child like to say, “You don’t find people to support the arts, you create them.” So we need more programs like Taller and Philadelphia Young Playwrights that teach school aged children not only how to appreciate the arts but also how to participate in them. As theater artists we are stewards of a very powerful legacy, and if we want this art form to thrive and continue we have to foster interest and excitement in a new generation.

Phindie: How is the theater situated differently in Latino and Anglo cultures?

TG: One of the points that got the biggest reaction when I was speaking in that first PNPI panel was “As a theater you have to figure out why a community will pay $60 for a fight, $20 for a movie ticket, but they won’t pay $15 to go see your plays. What about how that fight is marketed to them is more exciting than what you are selling? What is it about that movie, which they will soon be able to find on Netflix, that has so much more immediacy and relevance than your play? Do they even know about you? Do you go to the places Latinos congregate—community centers, churches, schools, restaurants—to advertise your work or do you hit up the same mostly Latino-free coffeehouses to peddle your theatrical wares over and over again? Will they see their struggles? Will they hear voices like their own?” Latinos are some of the greatest storytellers in the world. It is in our blood, in our brow, in our hands. Philadelphia has to find a way to make that dinner table storytelling into an interest in the theater because they share so much in their origins and transformative powers.

My mother wanted me to add: “Is it important to note that as a Latino community we also love storytelling that crosses boundaries. So, while we love West Side Story and In the Heights, we also love Funny Girl and Jesus Christ Superstar and the Book of Mormon and Rent and Mamet and Death of a Salesman and The Glass Menagerie and Porgy and Bess because the stories are beautiful and well told.” She’s a brilliant woman.

Phindie: What else can be done to increase Latino audiences and opportunities for Latino artists in Philadelphia?

TG: Keep working to create spaces for your story to be heard, whoever you are. One of the things I talked about in the PNPI panel where I first got involved with 30/30 is a story that Mindy Kaling tells about how she became a writer. In her book Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me? she talks about her love of comedy, especially romantic comedies. But she realized quickly that there were no actresses that looked like her in those sorts of comedy roles. So she wrote and starred in a two-woman show with one of her best friends which eventually got her discovered. And even though she knew little about writing for television she took the job at The Office because she wanted to create a place for herself to be a comedian. She is still doing that. Writing, producing, creating the highly successful show The Mindy Project so she can be the lovely, smart, quirky Indian rom-com star that didn’t exist in America before she came along. So don’t wait for permission. Don’t fear rejection from a system that was not necessarily set up to include you. Surround yourself with people who will make you unstoppable with their belief in your talents.

Don’t wait for someone else to invite you to the table. Build one yourself.

Phindie: Thanks Tamanya!

30/30 series:

To Catch the Lightning by Carmen Rivera, June 9.

El Nogalar by Tanya Saracho, June 16.

Dark Matters by Oliver Mayer, June 17.

[Plays & Players Theatre, 1714 Delancey Place] June 9-17, 2014; playsandplayers.org.

Amazing!