In general, theater reviews tend to present photographs that favor actors; yet, a great deal of creativity comes through the work of designers, technicians, and many others—all part of a creative team.

In the final part of this three-part series of interviews with Bernard Havard, president & producing artistic director of the Walnut Street Theatre, America’s oldest continuously-operating theater, Bernard shares his experiences with his creative team for A Woman of No Importance by Oscar Wilde: Scenic designer Dr. Roman Tatarowicz, lighting designer Shon Causer, sound designer Christopher Colucci, and costume designer Mary Folino.

Entering an aristocratic Alice in Wonderland world, peopled by fantastic Victorian characters:

Scenic designer Dr. Roman Tatarowicz

Henrik: Before the play started, we saw a rich, upper-class environment through a gauze curtain, as if we were about to enter an aristocratic Alice in Wonderland world, peopled by fantastic Victorian characters—all set in an awe-inspiring design by Dr. Roman Tatarowicz, “chair of the obstetrics department at St. Mary Medical Center in Langhorne” and one of the most sought-after stage designers for miles. He was quoted as saying that he found his stage work “humbling because some of the people I work with are crazy talented.”

What was it like working with this “crazy talented” scenic designer?

Bernard: We found him through our production manager, Siobhán Ruane, who was aware of his work. Having Siobhán on our staff has been a tremendous asset for us. She introduced me to Roman, and I saw his portfolio. I thought the work was amazing, and we immediately got him under contract for a show in the studio, and it just grew from there.

He’s worked on two shows that I directed, The Humans and then this show. He’s a wonderful collaborator. He not only studies the script thoroughly to inform himself as to the design, but he will also talk to me in great detail about my vision for the piece, leading to great collaborations.

The only thing that I had to talk to Roman about was the final act set for A Woman of No Importance. He was doing it in the same design as the grand mansion, and I said, “No, it’s a different world altogether. She lives in a cottage. It has to portray purity. There has to be a great change. All the flowers have to be white, absolutely white.” And I said, “I want a crucifix on the wall, because she has devoted so much time to religion and her church.” So with that collaboration, he came up with that wonderful set for us.

Henrik: When you shared your interpretation of the last act with Roman, how did he respond?

Bernard: Oh, he immediately drafted a new set. Immediately. And I said, “You got it; you understand.”

Beyond collaboration with me, Roman is also a great collaborator with the costume and the lighting designers. He doesn’t need to collaborate with the sound designer, although I’m pretty sure he would’ve told me if he thought it was wrong.

Roman’s hands-on. He goes down to the shop to make sure the scenery’s being built properly. He’s there the whole time the set’s being put in the theater. How he finds the time to leave the hospital and be at the theater for as long as he does, I’m not sure. Maybe he’s got great assistance at St. Mary’s.

Henrik: I have never heard of a physician who also creates some of the finest stage designs.

Bernard: Same here. I believe Dr. Tatarowicz is the only set designer I’ve ever worked with who delivers babies. He brings such a vision and precision to his work that I can only think that these skills make him an excellent obstetrician.

You know how Leonardo da Vinci was able to encompass the scientific and the artistic worlds—that’s what Roman does.

Working with a sensitive and aware human being and artist:

Lighting designer Shon Causer

Henrik: Could you describe your overall approach working with the creative team, starting with lighting designer Shon Causer, and how all their arts and skills contributed to this production of a difficult play with some of Wilde’s most famous quotes?

Bernard: Shon and I have collaborated on a number of plays that I directed at the Fulton Opera House and then moved to the Walnut, and he also worked on The Humans with me. He’s a sensitive and aware human being and artist. He understands light and the importance of it.

Henrik: For instance?

Bernard: Hester is overhearing these women prattling on about men and about society, and she’s off in a corner by the bookcase, and she’s sort of in a very dim light, so nobody really pays any attention to her. She’s just there. We know she’s there, and at the moment that attention is drawn to her, we slowly bring the light up on her, not so fast that the audience realizes what’s going on, but to focus the attention on her now.

Shon understands that, so we don’t have to have a long discussion about it.

For example, he knows that the first scene is outdoors. To try to help the audience understand, we use gobos—pieces of metal or glass with a design carved into them, in this case, leaves. Once a gobo is inserted, it projects whatever is carved into it. As a result, we get a dappled lighting effect coming through the trees.

Shon and I discussed whether they had electric light at that mansion, and we decided they did not. They were rural people, and they were probably still working off gas light in that building. Whatever adjustment he made to the color or the temperature of the lighting, it conveys gas light.

Henrik: You and everyone involved in this production must have spent an extraordinary amount of time and energy, let alone money, to make every moment work for your audience.

Bernard: True. We had the footlights at the front of the stage to convey gas light, and to heighten the fact that it’s theatrical. We’re not trying to fool anybody. A Woman of No Importance is a theater piece, and we hope audiences enter into it as a theater piece. We’re not trying to create reality as such; rather, we’re trying to convey the truth and the honesty of the situation.

“We’ve been on the same wavelength for a long time”:

Sound designer Christopher Colucci

Henrik: You also worked with your sound designer Christopher Colucci on creating specific moods.

Bernard: Yes, Colucci and I, we’ve been on the same wavelength for a long time. We think, “What is the mood that we’re trying to set?” I wanted a pastoral mood, because they’re in the country. We also had to deal with that big melodramatic moment when Hester comes screaming out after having been kissed by Lord Illingworth.

And at that point, it’s so melodramatic that I thought, if we cover this with a sound effect in the music, it will help the audience. If there’s nervous laughter in the audience, it’ll be covered to a certain extent. And it was successful, I think, in doing that.

Henrik: What music did you play during those tension-filled moments?

Bernard: The two composers that I was focusing on were Vaughn Williams and Gustav Holst. As soon as Hester comes on and says, “Lord Illingworth tried to kiss me,” and then the seducer appears onstage, and young Arbuthnot goes charging across the stage to punch him, Mrs. Arbuthnot makes a shattering revelation. At that point, the music chords strike. Badoom. It helps deflect, I think, nervous laughter from the audience, who may find this scene either tragic or overly melodramatic.

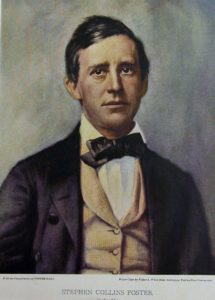

And also, the piece that’s played by Hester on the violin is American music from that period. I think it’s Stephen Foster. I said to Colucci, “Find me a piece of music that would’ve been played in America that she would have learned to play. And I’d like it to be specifically American, and not a piece of Beethoven or Bach or something.” So that’s what he did.

“Costumes give the audience information about the characters before they even speak”:

Costume designer Mary Folino

Henrik: One of those “crazy talented” people at the Walnut, Mary Folino, your costume designer, once said, “Costumes give the audience information about the characters before they even speak. And they help define their personalities, just as anyone’s clothes do.”

In this production, the men are dressed in dark outfits that represent their social and professional status. The women are wearing exquisitely elegant Victorian outfits with various colors and shades, with two exceptions: the American visitor dressed in white, and Mrs. Arbuthnot dressed in all black, almost like an angel risen from the dead (played by Alicia Roper, demonstrating a wide range of feelings).

Could you describe Folino’s work at the Walnut and her costume design for this production in particular?

Bernard: The first costume you see the young American in is pale off-white, slightly yellow, and the last dress she wears in Oscar Wilde’s Act 4 is white, white muslin. It’s also informed by Parisian fashions at the time, because of Wilde’s reference to “American women always get their clothes in Paris.” So when Mary researched the period and the costumes, she also researched what costumes, what dresses were being designed in the early 1890s in Paris.

The black dress, worn by Mrs. Arbuthnot, was only for Act 2 and 3, and it’s called for. Oscar actually refers to the “woman in black,” and so Lord Illingworth immediately says, “Yes, what a charming woman in black.”

The costume is also spelled out for Hester, the young American girl. It has to be a woman in white muslin. Oscar Wilde has put it in the script, in the dialogue. You would be absolutely foolish, and wrong, if you didn’t follow Oscar’s direction.

Turning the wit of a great writer into a living work of art on stage:

Director Bernard Havard on Oscar Wilde

Henrik: Bernard, you lived with this work for quite some time. Which quotes from this play seem to represent the wit and the biting satire of A Woman of No Importance for you?

Bernard: “The only difference between the saint and the sinner is that every saint has a past, and every sinner has a future.”

“To win back my youth, Gerald, there is nothing I wouldn’t do—except take exercise, get up early, or be a useful member of the community.”

“The English country gentleman galloping after a fox—the unspeakable in full pursuit of the uneatable.”

There’s just wit everywhere. There are so many quotes in this play, each one more famous than the next. I love them all.

Henrik: Tell us something that very few people know about you.

Bernard: The one thing I will tell you that I did in the past that informs my life is work as a short order cook and a sous chef in London, even though I didn’t get that far. I was cooking to support myself as a young actor, rather than driving a taxi or working as a waiter.

Preparing meals for people and seeing the satisfaction they get from a well-prepared meal is the same satisfaction I get from preparing a well-prepared play.

Henrik: I appreciate the way you greet people on opening night. As a theater reviewer, I feel always honored, as if you were saying, “You’re all doing a lot of hard work, too.”

Bernard: It’s a brotherhood. The people who support the theater are not a large group, probably less than, I don’t know, 3% of our country who enjoy what we’re doing. We have to embrace our audiences. They’re precious people. Without them, the theater doesn’t exist.

[Walnut Street Theatre, 825 Walnut Street] January 14-March 1, 2020; walnutstreettheatre.org