The Quintessential Synge

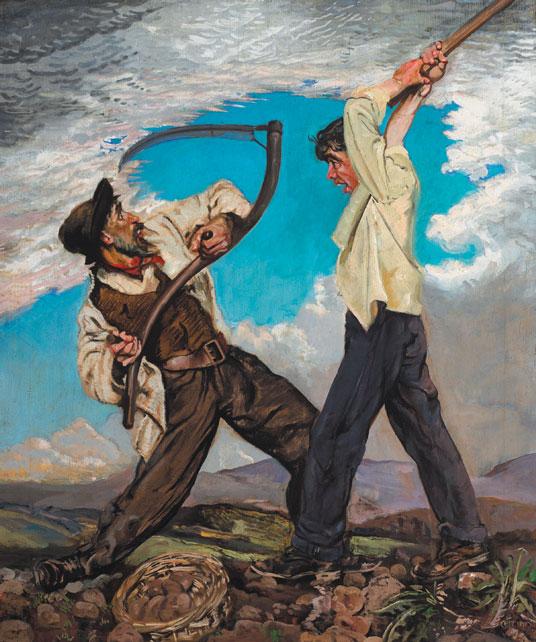

This Quintessence Theatre Group production at the Sedgwick Theater begins with a darkened stage, hauntingly beautiful music that conjures up Ireland, and then, for one second, we see a figure, frozen in time. Lights out. Another second, another man. In a fast sequence of stills, split-seconds of light followed by darkness (lighting design by John Burkland), we witness a Cain-and-Abel-like scene, except it’s a young son who kills his father with a loy (“small spade with a long handle, usually used for the digging of potatoes”).

Having just witnessed a murder most foul, we see young Christy Mahon—(Brandon Walters, discovered at an audition in NYC, who can change moods and stories within seconds)—dirty, disheveled, and anxious, staggering into Michael Flaherty’s tavern.

The pub owner—(Joe Guzman, one of Philadelphia’s leading men, whose energy added to the fast-paced production)—and his daughter Pegeen—(Melody Ladd, powerful as a young woman who has learned to stand up to men at the tavern)—find out that the young stranger carries a lot of anger with him, but also some remorse about his father, Old Mahon, a squatter—(Joseph Langham, successful film and TV actor who has performed in many theaters all over the US)—whom he confessed he killed without burying him.

In a lyrical moment, Christy describes his father as an earthy man, “going out in the yard as naked as an ash-tree in the moon of May, and shying clods against the visage of the stars”—language that resonates with anyone who hears him in the Irish village.

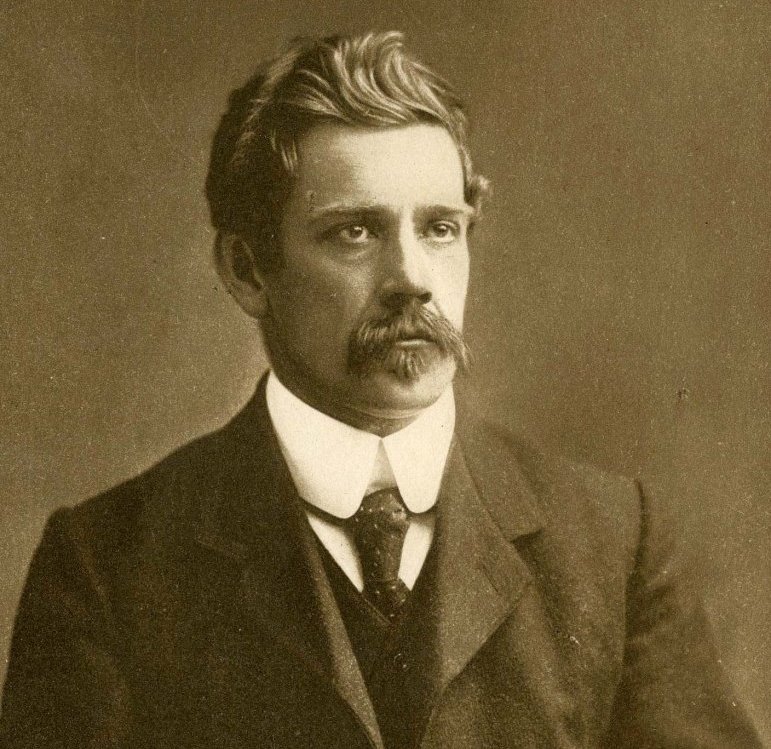

“I follow Goethe’s rule, to tell no one what one means in one’s writings”—Synge

Asked what he means in some of his many poetic scenes, Synge stated in a letter: “I follow Goethe’s rule, to tell no one what one means in one’s writings” (quoted in “Resisting the Irish Other: The Berliner Ensemble’s Production of The Playboy of the Western World” by David Barnett, New Theatre Quarterly, 33:2 (2017), pp. 156-68).

In its new season, Quintessence went all out with a detailed program covering four plays by Synge which they are performing this season, starting with The Playboy of the Western World, followed by The Synge Triptych, with Riders to the Sea, In the Shadow of the Glen, and The Tinker’s Wedding.

In his plays, over 100 years ago, Synge used language poetically and integrated Irish terms that many of us might not know.

However, thanks to the extensive “Synge Glossary” included in the program, we have a chance to learn about a world that, on the surface, may seem far removed to a modern non-Irish audience, for example:

cess (“expression meaning bad luck, derived from the practice of assessment of the Irish for provision of British Military forces.” “Bad cess to ya” is a common curse meaning, “may you come to a bad end”),

droughty (“thirsty”),

gob (“worthless youth with a foul mouth”),

lepper (“as in one who leaps”),

peelers (“policemen established by the British, from Sir Robert Peel, founder of the Irish Constabulary”),

shebeen (“an unlicensed or illegally operated drinking establishment”),

union (“a poor house or public assistance work house”).

In another example of Synge’s poetic language, Christy tells his gruesome story in a most lyrical way: “‘God have mercy on your soul,’ says he, lifting a scythe. ‘Or on your own,’ says I, raising the loy.”

Ashley Izard makes the peasants of Hieronymus Bosch come alive on the stage of her face

The stories of the young outlaw keep the father and his daughter Pegeen awestruck. The more interested his hosts become, the more the fellow on the run senses an opportunity to start a new life, perhaps working at the pub, drinking beer all day long, and marrying Pegeen. Soon, he loses all sense of remorse.

Within no time, word gets around that a “queer fellow” has arrived, and villagers fill up the tavern. All of them obsessed with the mysterious stranger, wanting to know all his secrets. Seeing the young man alone, the Widow Quinn—(Megan McDermott, convincing as the beguiling seductress one moment, demanding and forceful the next)—sneaks into the pub, uninvited, to make her claim on him, but fails to convince Christy to live with her in spite of her bold advances.

One of the country folks, an older woman—(played by E. Ashley Izard, one of the stars that artistic director Alex Burns has assembled in this cast of eleven)—makes so many constantly-changing facial expressions of delight, surprise, inquisitiveness, horror, contempt, and any other human emotion that she reminded me of the surreal paintings showing medieval peasants by Hieronymus Bosch, now come alive on the stage of her face.

She presents Synge’s world through her instant responses to anything being said or done by the stranger and her fellow peasants. Frequently, she shifts her movements through a myriad of gestures, executed with the precision of fully trained facial muscles.

A poor country woman who lives out all her hopes, her fears—it is as if all the peasant women around the world had been her ancestors. Just watching her is worth the price of an annual subscription to the Quintessence Theatre.

Synge’s queer fellow and erotic moments on stage

With an even larger audience, Christy Mahon climbs up onto the bar like Elvis Presley with young groupies showering him with applause, gifts, and endless admiration—as if he were the Second Coming.

The rapture climaxes with the young hero, standing high up on the bar, exhausted from telling all his tall tales and interacting with his enthusiastic new disciples, with the young women throwing kisses at him, trying to touch him. But only one villager, a young man, also in love with Christy, has the nerve to do just that:

Honor Blake—(Daniel Miller, one of the hunkiest actors for miles)—takes the hero by his waist, lifts him up, face to face, and then slowly, very slowly, slides Christy’s body down his own body. Stunned, the audience screamed, gasped, and laughed.

Shawn Keogh—(Christopher Morriss, who looks like an Italian TV star playing the role of the straight-laced second cousin of Pegeen)—is in love with the innkeeper’s daughter, whom he wants to marry, once he gets dispensation from the local priest to marry his blood relative. However, Pegeen is not terribly interested in him because at the slightest provocation he goes running to the local priest, never standing up for himself or others—except when he realizes that the queer stranger, according to rumors, wants to marry Flaherty’s daughter.

Frightened and yet willing to persuade his shabbily-dressed rival to leave for good, Shawn shows backbone when he tries to bribe Christy, first by offering to give him a ticket on a ferry to America. Anxious to make the deal, he then takes off his expensive tweed jacket—(costume designer Summer Lee Jack).

Sitting on the floor of the pub, he then takes off his fine leather shoes, and then he slowly pulls off his trousers, sitting half-naked on the stage—to the delight of the make-believe murderer, who accepts all the gifts with a sneer. Now well-dressed, Christy is only more determined to marry Pegeen.

The rise and fall of “the only playboy of the Western world”

Suddenly, Christy’s father, angry Old Mahon, with a frightening gash covering his entire skull, still blood-red—(makeup special effects artist Mandah K. Law)—arrives in the village, searching for his son who almost killed him. They clash again, first with a verbal round, leading to a deadly violent physical fight—(powerfully choreographed by J. Alex Cordaro)—bringing back the opening freeze-scenes.

Seeing his angry father brings up old power and control issues. Losing his temper again, Christy brutally attacks his father one more time, killing him. Christy realizes that with his renewed attempt to kill his father with the loy, the tide has turned against him.

Outraged, the same people who had previously praised Christy for all his mysterious and titillating stories about murder, now turn against him and try to hang him with a thick, long rope. Even Pegeen, who was ready to marry him, now sees him as a liar and a manipulator. She declares, “There’s a great gap between a gallous [wicked] story and a dirty deed.”

Seconds before Christy can take his last breath, Old Mahon returns. The terrible gash on his head as frightening as before, he staggers in, his face covered in blood. After a final power struggle between father and son, won by the audacious short fellow, both leave the village for good to wander the world. Feeling alone and deserted, Pegeen regrets the chain of events: “I’ve lost the only playboy of the western world.”

Classic Synge, classic Burns

Synge’s poetry flows from the lips of the most experienced actors as if they had lived in Ireland all their lives (dialect coach Sonja Field), while some younger actors sound as if they had only recently kissed the Blarney Stone.

Burns’ work as a director brims with originality that seems to know no bounds, even though he meticulously follows the text, down to the minutest details. For example, Synge wanted Christy—the “queer fellow” with the capacity to tell tall tales and tower over everyone else—to be short and come with small feet, thus underscoring the struggle of a young man who wanted to be bigger than he really was.

Consequently, Burns searched for the young hero among the best actors in Philadelphia and New York, and eventually, at an audition in the Big Apple, he found the talented short protagonist:

Brandon Walters as Christy Mahon came with the lively spirit of an Irish character who can tell tall tales so convincingly and changing his mood so quickly that the young folks in the village followed him like a pied piper, hanging on every word that came out of his mouth, observing every movement of his body with lust and desire. In short, he looked like a handsome, dirty blond, seductive Puck.

In productions directed by Burns, we get to see great actors of all ages and backgrounds. In this case, they seem to come straight out of a medieval village, in spite of their jeans. Burns is not afraid of showing human love and eroticism, often in vignettes that one cannot forget.

No matter when and where a story takes place, director Burns integrates one or more people of color into his shows, as in this production. His casting makes us aware of the wide range of human experiences where “black” is more than a skin color, where “black” is not an outsider, but very much part of the rainbow of life—even though purists may insist on productions that strictly follow a playwright’s gender and ethnicity-prescribed roles.

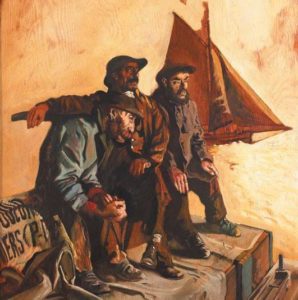

With the border almost closed off to “aliens”—Synge’s Irish refugees arrive at the U.S. wall

Quintessence Theatre Group—Philadelphia’s 18th Actors’ Equity theater and one of the few repertory theaters in the Greater Philadelphia area—frequently dares to present new perspectives through their productions, whether directed by Burns, the founding artistic director, or by guest directors like Rebecca Wright.

The final moments of the Quintessence production hit me hard when something unexpected happened on the stage that I will remember for a long time to come. Blindingly-bright lights hit a gigantic American flag that covered the entire back of the theater, with the stage in darkness. Flashlights, like searchlights, allowed me to see only a lonely figure coming forward.

The director described the last few moments of this Synge drama in a private note to me:

“Christy throws his fist in the air in triumph, because we all know how chutzpah, a smile, and a good tall tale can take you to the top in America. [. . .]

“As the immigration debate rages, and as our current leader’s rise is also built on ‘the power of a lie,’ or in his case, lies, there are many resonances that I hope the finale will stir up for our audience.”

A few seconds later, a second man arrived on the darkened stage: his much-taller father, Old Mahon, carrying their only suitcase—walking slowly into an unsafe and unpredictable new world for refugees.

Then all the Irish characters came up on the stage. The Quintessence ensemble took a bow. My joy mixed with tears, because I suddenly became aware again of the oppression that the Irish had endured for a long time under brutal British rule, and the harsh treatment of desperate refugees arriving at the U.S. borders in our own time.

I drove home, thinking about Ireland and frightened immigrants, and all the things we had experienced that night at the Sedgwick Theater.

Quintessence Theatre Group is performing and reciting the Barrymore-nominated complete works of J.M. Synge: The Playboy of the Western World and The Synge Triptych till October 27, including readings of his poetry and other plays.

[Quintessence Theatre Group at the Sedgewick Theater, 7137 Germantown Avenue];