Everybody seems to be writing about the 50th anniversary of Stonewall so I thought I’d offer my own contribution.

I was not at Stonewall, so I never saw the first brick or rock being thrown but I was miles away in Boston where I heard about it the next day in the Sunday Times. Sometime later I read what poet Allen Ginsberg said about the Stonewall riots. The poet, a New Yorker, had rushed to the scene after the riots broke out and was quoted by the press as saying that Stonewall had caused homosexuals to lose “that wounded look.”

1969 was the year I went looking for Judy Garland in Boston’s Napoleon’s Club, one of the singer’s hangouts. It was the year that I heard Anais Nin lecture at Harvard while working as an operating room orderly to fulfill my alternative service contract as a conscientious objector. My days were filled with observing autopsies, brain surgeries, mastectomies, amputations and countless therapeutic abortions. It was the year that Trappist monk Thomas Merton was electrocuted in Thailand and when I met and escorted famed Bauhaus architect Walter Gropius to the operating room—an operation that would lead to his death several days later.

It was the year that I first started to go to gay bars. Just where these gay bars were was anybody’s guess. There were no tourist brochures, no gay guides. My only recourse was to go into one of the adult bookstores in Boston’s Combat Zone and ask a clerk. He directed me to the Punch Bowl, a favorite hangout of actor Robert Mitchum and dancer Rudolph Nureyev when they were in town. Dancing was forbidden in the Punch Bowl and sometimes everyone was told to stand still and be quiet when the lights went on. That meant that the police, or undercover mafia, were in the bar for their payoff.

The same thing happened at Sporter’s bar on Cambridge Street near Massachusetts General Hospital. When the lights went on you knew to disengage if you were holding hands (or worse, kissing). We’d watch as the pay off guys went into a back room or the manager’s office. The lights would go out again after they left.

After the Stonewall riots gay publications began to appear among the counterculture underground newspapers at the MBTA Harvard Square station. Underground newspapers like The Old Mole called for a revolution, an end to the Vietnam War and civil disobedience but the newspaper had no time for fags. The word fag was always cropping up in the pages of The Old Mole. It made me suspicious of the people whose side I was supposed to be on. These so called revolutionaries were every bit as bigoted as their Reader’s Digest reading parents.

After the Stonewall riots gay publications began to appear among the counterculture underground newspapers at the MBTA Harvard Square station. Underground newspapers like The Old Mole called for a revolution, an end to the Vietnam War and civil disobedience but the newspaper had no time for fags. The word fag was always cropping up in the pages of The Old Mole. It made me suspicious of the people whose side I was supposed to be on. These so called revolutionaries were every bit as bigoted as their Reader’s Digest reading parents.

I started writing for a newspaper called Lavender Vision. They let me title my first piece: Straight Amerika, the Moon is on Your Crotch. My second submission concerned the violent treatment of a transvestite in a friend’s Beacon Hill apartment complex. Two heterosexual couples in their twenties, very drunk and rowdy, had chased the transvestite out of the elevator in my friend’s apartment building. My friend and I witnessed the harassment and went running after them, yelling and berating them with colorful epithets. For a season or two I became virulently heterophobic.

At the hospital it was not uncommon to hear doctors and nurses use the word fag or queer. Often this occurred during operations or in the coffee room. “I went to Bermuda with my husband and we met this big queer dressed in all-white like a character out of Tennessee Williams,” I remember one anesthesiologist saying. Despite these occasional blips Boston was a very sexual and tolerant city, as noted by Gore Vidal once in a Gay Sunshine interview. Men were having public sex up the down the shores of the Charles River. Once I even saw a Hare Krishna monk lift his saffron robe before a kneeling taker who had just come from the bars. For the most part police ignored this activity but occasionally they would cruise the river in patrol boats with bright white lights and then shine them on suspect men, while announcing through a loudspeaker: “Okay, faggots, move on.”

I joined the Boston Gay Liberation Front and started attending meetings in a conference hall at MIT. We marched as a group in the Vietnam Moratorium Day on the Boston Common on October 15, 1969. 100,000 war protesters crowded the Common in the biggest demonstration held in Boston Common before or since. As Howard Zinn, George McGovern and John Kenneth Galbraith spoke to the masses we carried our Gay Liberation signs through the mass of demonstrators. Most of the people looked at us with mildly shocked frozen eyes. “Here,” I thought, “is the hand me down legacy of their parents—they simply can’t believe it.” The fact that only a few people shouted “Right on” was discouraging.

Our Gay Liberation group planned a big road trip to the Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention, organized by the Black Panther Party, in Washington DC on November 27-29, 1970. The first BPP convention had been held in Philadelphia in September of the same year. The Panthers were ambivalent when it came to gay men. Eldridge Cleaver in Soul on Ice had compared homosexuality to baby rape and wanting to become president of General Motors. Several Gay Liberation groups opted to ignore possible Panther hostility and participate in the convention anyway mostly because it was reported that Panther leader Huey Newton was supportive of Gay Liberation.

The Socialist Review credits French writer Jean Genet as changing Newton’s mind about homosexuality. In 1970, Genet was in America to speak about Panther causes. His translator at the time was Angela Davis.

“Davis also remembers that during his tour not only did he [Genet] not make any secret of his homosexuality, but he deliberately provoked debate — on one occasion by wearing drag — and argued with the Panthers about their homophobia and use of words such as faggot. She believes it was these arguments that later led to Huey Newton’s article in the Panthers’ paper arguing to support gay liberation.”

Newton also happened to be the best looking of all the Panthers so he became a darling of sorts for radical gay men. The Harvard Coop sold large posters of Newton sitting in a wicker chair. I quickly bought for my Cambridge kitchen wall.

Disunity and schism caused the Washington DC convention to be called off. Boston Gay Lib was ensconced in a house with other Gay Lib groups, some men done up in Mama Cass mixed print moo-moo dresses to go along with their long hair and beards. We drank cheap jug wine, danced circle dances, chanted and slept in sleeping bags on the floor. With the convention called off, the next day we zapped a Washington McDonald’s and danced together while construction workers ordered hamburgers.

Aping or emulating the patriarchy meant getting involved in exclusive love relationships. That kind of coupling up was frowned upon. Exclusive relationships as existed in the heterosexual world were based on the ownership principle inherent in capitalism. The party line then was: Gays are different. Lovers should be open to sharing and welcoming the “occasional other.” Monogamy was a sickness (on a par with wanting to becoming president of General Motors).

![]() How did this explain the reverential deference shown the unofficial leader of our group, a masculine Heuy Newton look-a-like and his younger, pretty white boyfriend? When we stayed at a big commune in New York City on the return trip to Boston a magnificent double bed with enclosed curtains was offered the pair while the rest of us had to sleep on the floor.

How did this explain the reverential deference shown the unofficial leader of our group, a masculine Heuy Newton look-a-like and his younger, pretty white boyfriend? When we stayed at a big commune in New York City on the return trip to Boston a magnificent double bed with enclosed curtains was offered the pair while the rest of us had to sleep on the floor.

The magical couple, in a nod to the Ozzie and Harriet patriarchy, wasn’t about to share anything. Had I found a clink in the socialist armor?

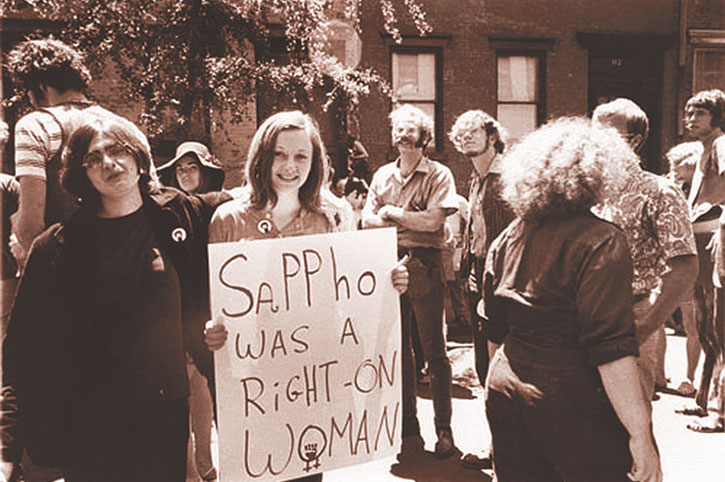

I attended the first New York City Christopher Street march one year after Stonewall in 1970. We marched and chanted as thousands ran to join the march from the streets. The gathering in Central Park was monumental. I returned to Boston where I found time to pass out Lavender Vision newspapers in Harvard Square on the weekends. Only women took a sample copy while the men would walk by, indifferent, as if in a trance.

From Boston I moved to Boulder-Denver, then back to Boston and then returned to Philadelphia where gay activism consumed nearly all of my writing. Boulder had a ramshackle Gay Liberation Front but it was mostly a party group that consisted of going to “straight” bars and dong dance zaps in front of macho Apache men who lived in the mountains.

I will skip over the Philadelphia portion of my life and conclude by mentioning a current feature article in The Atlantic about the end of the Gay Rights Movement. In that article the writer, James Kirchick, contends that the gay movement is really over. Gays have won, he writes, and while homophobia still exists (and needs to be dealt with) the organizational zeitgeist—the thrust and the central storm—is really over.

This may be true. As Philadelphia’s own Barbara Gittings once said, the goal of the gay movement is to make it an obsolete notion that a gay person should go to a gay church, join an all gay sports team or live in a ‘gay bubble’ because of the hostility of the outside world. The goal of the movement should be the erasure of that hostility so that the movement itself is no longer necessary.