Director Alexander Burns’ ambitious KING LEAR opens in the middle lobby of the Sedgwick Theater, where the audience watches from the sidelines as Lear tries to divide his lands among his three daughters, unknowingly planting the seeds of his kingdom’s ruin. White powder pours out onto a room-sized map of England on the floor, forming the new borders that Lear draws out, before the lines are inevitably scuffed out and erased.

Director Alexander Burns’ ambitious KING LEAR opens in the middle lobby of the Sedgwick Theater, where the audience watches from the sidelines as Lear tries to divide his lands among his three daughters, unknowingly planting the seeds of his kingdom’s ruin. White powder pours out onto a room-sized map of England on the floor, forming the new borders that Lear draws out, before the lines are inevitably scuffed out and erased.

The members of the court enter waltzing, on display before the king, with the two oldest daughters well-matched to their husbands and Cordelia paired with the much-shorter Fool, who capers about, throwing her off her stride and making her smile. Compliments for the mix of elegant and humorous choreography go to Janet Pilla Marini.

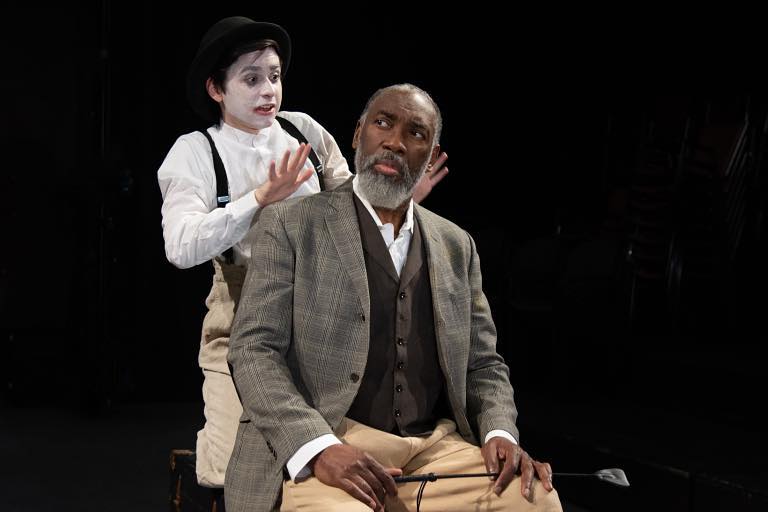

Probably the youngest actor on the stage, particularly diminutive in comparison with Lear, DJ Gleason shines as the Fool. Painted like a French mime with a broad Jersey accent, he cavorts about the stage with bawdy humor and genuine affection for Lear. Alex Burns explained that he envisioned a young Fool from the beginning, and he found the right actor in Gleason, who appeared in Quintessence’s recent production of Awake and Sing!

Tall, grey-bearded Lear, played by Robert Jason Jackson, is “every inch a king,” as Lear calls himself. Jackson’s powerfully resonant voice inspires awe in the audience—his royal subjects. He cuts a forbidding figure seated on the throne or, later, railing against the elements as he strides into a storm.

Shattering his expectations, however, Lear’s test of his three daughters’ loyalty spins out of his control. Donnie Hammond and Anita Holland as chronic backstabbers Goneril and Regan, respectively, dupe their father into believing that they love him more than life itself. Like real sisters, the actors playing these duplicitous daughters seem to communicate with each other as well as the audience with split-second smirks that reveal layers of contempt.

In a stunning reversal, the quietly devoted daughter Cordelia (Eunice Akinola) sparks Lear’s anger by failing to flatter him, leading him to denounce and banish her.

Grieving, Cordelia leaves with the king of France, played regally by Jahzeer Terrell, who also appears in various ensemble roles, along with Connor May.

Oswald—a minor character rendered memorable by how much actor Ben Salus seems to enjoy camping it up—invites the audience to move into the next room.

Tragic heroes and villains

In a gender-flip, E. Ashley Izard plays the Earl of Gloucester as the mother of two sons: Edgar the legitimate heir and Edmund the bastard. The breezy way in which she acknowledges her illegitimate son, smiling at the memory of his conception, takes on a new potency coming from a female Gloucester. In our political climate today, seeing a poised and authoritative woman eventually cut down feels like art imitating life.

J. Hernandez plays Edmund not as a cool, unflappable strategist, but with boundless energy that he channels into the plots to feed his ambition. Cleverly engineering his brother Edgar’s downfall while pretending to take his side, Edmund begs his mother on his knees to please, please not be so hasty in blaming Edgar. The crocodile tears streaming down his face almost had me persuaded—at least for a second or two. Villains often captivate audiences far more than heroes.

By contrast, Edmund’s brother Edgar suffers from being the “good son” the way Cordelia suffers from being the “good daughter.” Jake Loewenthal carries off the challenges of the role with aplomb, transforming himself into Edgar’s various disguises through voice and demeanor. His portrayal of feigned madness as “poor Tom” at times gave me a shiver.

Michael Liebhauser plays a very young Albany with strained, nervous energy, helpless to do anything to stem the tide of the tragedy all around him.

Kent, embodied by Gregory Isaac with a stubborn, steadfast heart, supports the king in all his trials. Quiet and dignified, his presence is nevertheless strongly felt throughout. His character displays the ultimate loyalty to Lear: “I have a journey, sir, shortly to go;/My master calls me, I must not say no.”

The creative team: stage design, costumes, sound, and light

The set, also masterminded by artistic director Burns, incorporates a round raised platform that could be spun by the strength of one or two people crouched on the stage floor, applying their strength like Atlas holding up the heavens. Its best use comes in the most gruesome scene in the play, in which Regan and Cornwall interrogate Gloucester, appearing to circle around her like vultures while she is tied to a kicked-over chair in the center of the large disk.

Presenting a particularly brutal Cornwall, Lee Cortopassi brings out an animalistic side to the character. As Regan, Holland opportunistically seizes on Cornwall’s weakness. In a macabre detail that amplifies Cornwall and Regan’s sadism, they both pace around Gloucester in high heels, sharp enough to puncture skin—if that’s not giving away too much of what happens.

The dagger-like heels stood out as one of many creative costuming choices by Quintessence senior costume designer Jane Casanave, including the Fool’s Chaplin-esque bowler hat and makeup, the riding crop that Lear toys with, or the sisters’ lavish fur coats. However, I wished for a more unifying theme to pull together the costume pieces from disparate historical periods and styles.

The creative anachronisms extended to Burns’s drama-enhancing musical interludes, which ranged from classical to EDM.

Ellen Moore designed lighting that creates striking, time-stopping effects in some scenes, but I think a less-is-more approach could have been even more effective at underscoring tense moments.

The famous storm scene benefits from not being overloaded with lightning and thunder, giving Jackson full rein to display Lear’s inner tempest. The scene also marks the beginning of Lear’s precipitous decline. Hands shaking and voice faltering, Jackson conveys the weight of Lear’s fragility.

These moments of weakness in Lear, culminating in his reconciliation with Cordelia, draw out the audience’s sympathy for the once-great king. Eunice Akinola’s balancing of Cordelia’s sweet and guileless side with her steely resolution brings out the best in the scenes between them.

“Is this the promised end?”

At the top of Act Five, with a war brewing, Gloucester blinded, Lear and Cordelia captured by enemies, and their allies scattered, Oswald once again asks the audience to move, this time from the inner chamber of the stage to the middle lobby for the finale.

At the top of Act Five, with a war brewing, Gloucester blinded, Lear and Cordelia captured by enemies, and their allies scattered, Oswald once again asks the audience to move, this time from the inner chamber of the stage to the middle lobby for the finale.

The immense map of England provides the dueling ground where Edgar finally confronts Edmund. Assistants pressed a few audience members back, like groundlings, lest they stray too close to the action—making room for the flashing swords, realistically choreographed by Ian Rose.

All of Goneril and Regan’s cunning plans undone, they die, consumed by the need for power. With their bodies and the whole of England at his feet, Lear enters for the last time, dragging Cordelia behind him in a huge white shroud—too weak to carry her in his arms, just as he was too slow to prevent her from being killed.

Lear addresses Cordelia’s body in anguish: “Why should a dog, a horse, a rat, have life, /And thou no breath at all?”

Listening to his final speech, we have to wonder how far gone Lear’s mind really is. Can he see the full scope of the tragedy that has played out before our eyes—or does his madness at least save him from that knowledge?

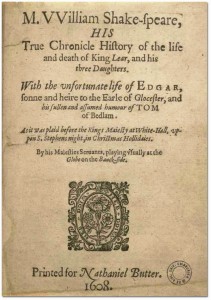

[Quintessence Theatre Group at the Sedgwick Theater, 7137 Germantown Ave. (Mt. Airy)] March 19-April 20, 2019; quintessencetheatre.org