Baseball in Philadelphia is riding on a wave of success by the hometown Phillies, winners of four straight National League East titles and two of the last three National League pennants. No one who saw the joyous celebrations that followed the team’s 2008 World Series victory or the excitement that built in their 2009 and 2010 playoff runs could doubt the depth of support that runs across the Philadelphia area. And well it should: the city boasts a rich and storied baseball history, with a legacy stretching all the way back to the very beginnings of the game.

One of the earliest mentions of a game resembling baseball came in a 1778 diary entry made by a young Revolutionary War soldier camped at Valley Forge just outside Philadelphia, who observed troops playing a game of “base.” Philadelphia was also home to the first organized baseball club, the Olympic Ball Club, formed in 1833 by a group of young gentlemen from the cream of Philadelphia high society. The games these men played would be barely recognizable to fan of the modern sport, with irregular numbers of players, innings, bases, and batters. By the 1860s, however, the Olympic and other Philadelphia ball clubs, made up of men from all walks of life, were playing by the rules of the New York–based National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP)—a game that would soon evolve into America’s favorite pastime.

One standout team among Philadelphia’s early baseball clubs tried unsuccessfully to gain admittance to the NABBP. The reason behind their refusal was clear: the Philadelphia Pythians was made up of African American players and led by short-stop Octavius Catto, a pioneering voting rights campaigner who was assassinated in 1871 for his political activities.

As segregation became institutionalized into baseball, another Philly team, the Athletic Club of Philadelphia, was becoming a powerhouse of the early sport, compiling the best record in the nation in several seasons and winning the inaugural championship of the National Association, the precursor to the major leagues. In 1876, the team was a founding member of the National League of Professional Ball Clubs, the world’s oldest extant professional sports league. They were kicked out of the new league after its maiden season, but by this time Philadelphia was well-known as a center of baseball and a key birthing ground for the sport’s early professionals.

Seeing that they couldn’t survive long without a team in baseball’s heartland, the National League asked former ballplayer Al Reach to found a new franchise, the Philadelphia Phillies, in 1883. This birthdate makes the Phillies one of the oldest organizations in professional baseball, and the oldest to have kept the same name and hometown for its entire existence. The history is long, but the successes are few. Their first season record was a dismal 17- 81 and the team did not win its first pennant for over thirty years.

While the Phillies were wallowing in years of mediocrity, Philadelphia was blessed with its share of winners. In the Negro Leagues (as the all–African American competitions were known), the groundbreaking Pythians were followed by a series of successful franchises: among them the Hilldales, winner of the 1925 Negro World Series; and the Philadelphia Stars, champions of their league in 1934. Both teams played occasional exhibition games against the city’s white teams, defeating their segregated rivals with some frequency.

These rivals included one of baseball’s most successful white outfits, the reformed Philadelphia Athletics, who began playing in 1901 as a founding member of the American League. Coached and partially owned by former catcher Connie Mack, the team quickly established itself as the first dynasty of the new league, winning six pennants and three World Series (1910, 1911, 1913) before the Phillies won their first National League title in 1915. After a few dry years following a surprise 1914 World Series loss, the Athletics bounced back to win back-to-back championships in 1929 and 1930, adding a third-straight American League title in 1931.

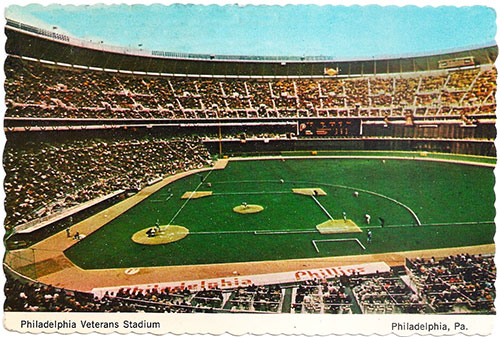

Much of the Athletics success came at Shibe Park (later renamed Connie Mack Stadium). Situated in North Philly at 21st and Lehigh, he ballpark was a state-of-the-art structure when it was completed in 1909 and served as the home of the Athletics until their relocation to Kansas City after the 1954 season. (They currently play in the Bay Area as the Oakland Athletics.) The Phillies joined the Athletics at Connie Mack Stadium in 1938, leaving the dilapidated Baker Bowl, where they had played since 1887. Connie Mack’s crowded schedule also included Monday night games by the African American Philadelphia Stars, who regularly drew larger crowds than their white counterparts. The Phillies called the ballpark home until 1970, when the deteriorating neighborhood and antiquated structure forced a move to Veterans Stadium in South Philadelphia.

These stadiums saw more than their fair share of heartbreak. A new crop of “Whiz Kids,” that included Hall of Fame centerfielder and longtime Phillies announcer Richie Ashburn, seemed destined to break the Phillies decades long title-drought in 1950, winning the National League before being swept by the New York Yankees. But this brief flirtation with success was followed by another long spell of failure as the Phillies organization stubbornly and shamefully refused to integrate their team. Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier in 1947, but it would be another decade before the Phillies accepted the new reality, finally becoming the last National League team to field a black player in 1957.

A belated recruitment of such star black and Latin American players as Richie Allen and Ruben Amaro, Sr., led the 1964 Phillies to the brink of playoff success. With 12 games remaining, the Phillies led the St. Louis Cardinals by 6½ games. They proceeded to lose the next 10 games, a “September Swoon” that would loom large in Philadelphia lore.

The Phillies’ mediocrity (and sometimes downright awfulness) continued until the mid-1970s. With the National League now divided into two divisions, the Phillies made the NL championship game three times in a row from 1976 to 1978, but fell short of a World Series spot on each occasion. Star players Steve Carlton, Mike Schmidt, and future Phillies manager Larry Bowa were joined in 1979 by hitting virtuoso Pete Rose. The star-studded team finally broke nearly a century of Phillies underachievement in 1980 with a six-game World Series victory over the Kansas City Royals.

The aging team returned to the World Series in 1983, falling in five games to the Baltimore Orioles, but the 25 years that followed marked a low-point in Philadelphia sports. The city’s skyline was rising, as the construction of Liberty One in 1987 broke a longstanding gentlemen’s agreement not to build a structure taller than the brim of William Penn’s hat atop City Hall. For some, this heralded “the curse of Billy Penn,” as all four of the city’s major sports teams suffered a championship drought. The Phillies suffered a two decades rut interrupted only by the magical 1993 season. A group of rowdy, shaggy haired players such as John Kruk and Lenny Dykstra, led by starting pitcher Curt Schilling, captivated a victory-starved city, seizing an improbable NL East pennant, but falling at the final hurdle with a World Series loss to the Toronto Blue Jays.

Despite a long history of losing (the team’s 10,000+ losses exceed that of any professional sports team in the world), expectations ran high when the Phillies moved into their current home at Citizens Bank Park in 2003 under the management of Charlie Manual. The team did not disappoint. With a new generation of home-grown talent—MVPs Jimmy Rollins and Ryan Howard, star second baseman Chase Utley, and ace pitcher Cole Hamels—fulfilling their potential, the Phillies have not had a losing season in their new home [ed: until 2013].

In 2007, the Phillies finally lay to rest the memories of 1964 with a memorable September surge that saw them overcome a seven game deficit to the New York Mets to take the National League East. The following year, the team reversed the curse of Billy Penn, compiling a 11-3 postseason record (7-0 at home) and clinching the Phillies’ second World Series title in a famous rain-interrupted game five. Across Philadelphia, the joy was rampant, with parties along Broad Street going into the wee hours of the morning, and a victory parade that drew over two million spectators.

The second time was so nearly a charm as the 2009 team rode midseason signing Cliff Lee’s arm back to the brink of another World Series championship, falling to the New York Yankees in a hard-fought six-game series. They stumbled one step earlier the following year, compiling the best regular-season record in baseball in 2010 (the first time in the Phillies 128 years in which they accomplished this), but losing in the National League Championship Series to the San Francisco Giants.

The 2011 season began with expectations again high for the Phillies, who had one of the strongest starting rotations ever compiled, with former Cy Young Award winners Roy Halladay and Cliff Lee (back with the Phillies after a year at the Seatle Mariners and the Texas Rangers), three-time All Star Roy Oswalt, and 2008 World Series MVP Cole Hamels [ed: the Phillies would go on to lose in the first round of the playoffs].

From Octavius Catto to Ryan Howard, Connie Mack to Charlie Manual, the Olympic Club to the Phillies, Spring training to the Fall Classic, a rich baseball tradition lives on in Philadelphia.

Previously published by Morris Visitor Publications and Philly Fiction, republished by kind permission of the author.