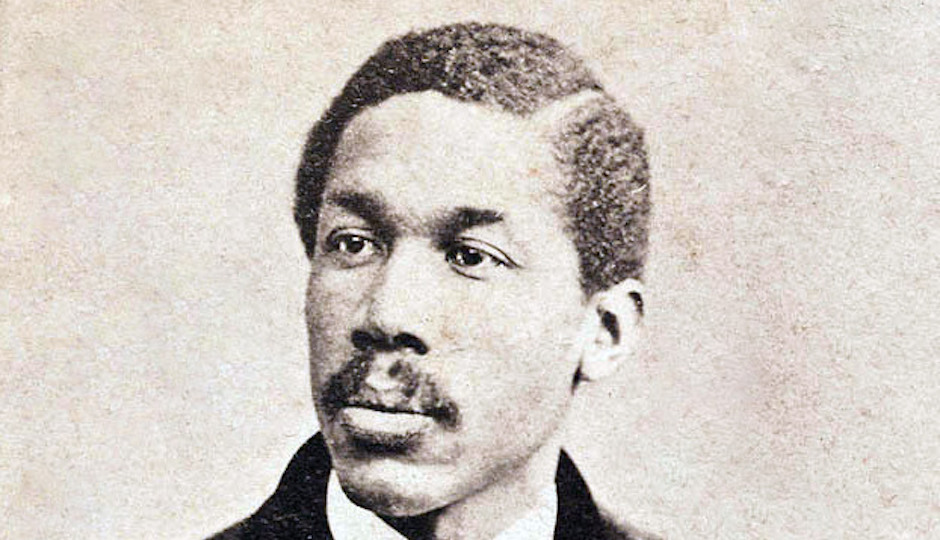

When we think of African American baseball we usually focus on the 20th-century Negro leagues or on Jackie Robinson’s integration of major league baseball. But black baseball has roots that go back to the end of the Civil War. In 1866 two Philadelphia ball clubs took the field, the Excelsior and a ball club affiliated with the Quaker-founded Institute for Colored Youth. Because a large number of Institute players were members of the Knights of Pythias Lodge, they soon adopted the name Pythians. The members met and stored their equipment at the old Institute for Colored Youth’s Liberty Hall at Seventh and Lombard. The first full scheduled season for the Pythians was in 1867 under their field captain and shortstop, educator and activist Octavius Catto.

For Catto, baseball was closely connected to his civil rights activism. In 1864 he had helped found the Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League and became corresponding secretary, while his friend Jacob White was elected recording secretary. Once the Pythians began competing, Equal Rights League and Republican Party members often attended home games. This fraternizing quietly laid the groundwork for many postwar civil rights actions.

By 1860, Philadelphia had over 569,000 residents, around 4 percent of whom were black. Philadelphia had the largest black community of any northern municipality; only the border city of Baltimore had more black residents. Philadelphia’s “colored” population was concentrated at the center of the old eastern city wards, with 42 percent of the city’s black residents living in the area extending from Fitzwater and South Street in the south, north towards Chestnut Street. The densest populated black section was in the Moyamensing-Southwark neighborhood of South Philadelphia, near places of domestic employment. Philadelphia’s black residents were a distinct underclass, economically disadvantaged and further challenged by competition from European immigrants, particularly the Irish. Concentrated in neighboring wards, the Irish asserted racial privilege and guarded their employment opportunities. Racial discord was commonplace.

Philadelphia’s black community was not completely downtrodden, however. Black leaders founded churches, benevolent societies, fraternal organizations, libraries, building and loan associations, and schools. Education was a priority, and after 1850 aspiring students took advantage of the opportunities offered by the Institute for Colored Youth. One such student was Octavius Catto.

Students at the Institute were taught higher mathematics, classical languages, literature, and philosophy as well as the ideals of individual freedom and equal rights. At the Institute, Catto met Jacob C. White Jr., who would become the Pythians’ secretary and Catto’s best friend. In 1858 Catto graduated with highest honors and after a year in Washington, DC, joined the Institute’s faculty. In his new position he proved to be an accomplished teacher, academician, and charismatic leader who took proactive positions on issues that moved him. In 1863 Catto organized and headed up a voluntary black company of soldiers. Although their service was rejected because of race, Catto was later appointed major and inspector for the Pennsylvania National Guard. He never saw action, but made a name for himself and developed political and community ties that served him well in his later campaigns for equal rights. In 1866, Catto’s politics led him to take a lead in the fight to desegregate the Philadelphia streetcars. He served on a three-man panel representing the Equal Rights League that successfully lobbied the state legislature to desegregate Pennsylvania’s streetcars. Another vehicle for Catto’s social and political activism was a competitive black baseball team.

During Catto’s years as a student at the Institute for Colored Youth, the dominant sport in Philadelphia was cricket. Catto excelled in cricket, but the Civil War interrupted the school’s daily sporting routines. When stationed at Camp William Penn outside Philadelphia, he was exposed to the popular bivouac game of baseball. After the war organized baseball became a competitive athletic outlet in the cities of the northeast.

Many of the ballplayers who made up the rosters of Philadelphia’s first black teams honed their skills playing town ball, an early baseball prototype, and cricket. Philadelphia had three black cricket teams, which played their matches in a lot at the northwest corner of 16th and Pine. The Pythians first played ball at Diamond Cottage Park in Camden, New Jersey, because of problems gaining access through the Irish neighborhood of Moyamensing to the Parade Grounds at 11th and Wharton. Eventually the Pythians prevailed and their first recorded game at the Parade Grounds took place on October 3, 1866, when the Pythians lost to the Bachelor club of Albany, New York, 70–15.

Philadelphia’s black community had a great interest in baseball and followed both white and “colored” ball clubs. At the start of the 1867 season the better-financed Pythians recruited players from their intercity rivals, the Excelsiors. These raids caused ill feelings and by the end of 1868 the Excelsiors had trouble fielding a competitive team.

The 1867 season was the Pythians’ first full campaign. They began the year by establishing a board of directors and electing officers. The Pythians selected the 28-year-old Octavius Catto as field captain and manager. The ball club played 13 games in 1867: 8 wins, 3 losses, and 2 games of unknown outcomes. The club secretary, Jacob White, organized these contests, corresponding with his counterparts and challenging them to games. The club then contracted ball fields, secured umpiring, and made arrangements for pre- and postgame festivities. Women affiliated with the club organized picnics, dances, and banquets, making these games community and regional gatherings that allowed black leaders to meet and discuss issues that transcended the ball fields.

During the 1867 season the Pythians played in Baltimore, Harrisburg, Camden, and Washington, DC. The contests in the nation’s capital against the Alert and Mutual ball clubs in particular brought regional black leaders together. In July the Pythians played both teams in Philadelphia, defeating the Alert in a rained-out four-inning game, 21–18, and losing to the Mutual in a close 44–43 contest. The return matches, played in late August in Washington, attracted large and enthusiastic crowds. Again the Pythians beat the Alert and two days later subdued the Mutual. At the second Alert game, the renowned abolitionist Frederick Douglas attended and watched his son, Charles, a desk clerk at the Treasury Department, play third base for the Washington club.

These efforts were undermined by the racism that pervaded the Pythians’ world. In October 1867 the Pythians applied for admission to the Pennsylvania Association of Amateur Base Ball Players. Nominated by E. Hicks Hayhurst, the vice president of the Philadelphia Athletics and president of the regulating convention, the Pythians, after much soul-searching, withdrew their application when it became clear that they would be denied admission because of race. Later that year, the National Association of Base Ball Players ruled against admitting any clubs that included black members.

Before the advent of the 1868 season, the Pythians completed their absorption of rival local ballplayers. By the summer the Pythians, wearing blue pants and a white bibbed shirt with a large gothic “P” on the chest, had four separate nines. With the exception of games played in West Chester and Harrisburg, the Pythians met their opponents in Philadelphia at the Athletics’ ball field at 17th and Columbia, the Parade Grounds at 11th and Wharton, and at an irregularly shaped field at 24th and Columbia where the Phillies began to play in 1883.

The 1869 season was the highpoint of the Pythians’ brief life. They allegedly played 14 games, but the results for 10 contests are not recorded. That year was also significant because of the club’s extensive travels and their contests against white teams.

The Pythians believed black credibility and acceptance could be promoted by competing against “our white brethren” on a baseball diamond. White clubs did not shy away from the Pythians’ challenges, believing a black team would play inferior ball. The first game of this kind was against the city’s oldest ball club, the Olympics, who played at 25th and Jefferson. On Friday, September 3, playing before a large and enthusiastic crowd, the Pythians lost to the seasoned Olympics 44–23. Col. Thomas Fitzgerald, the founding president of the Athletics and the owner of the City Item newspaper, served as umpire. A return match was set up for October but was probably never played. Two weeks later the Pythians did play and defeat Fitzgerald’s white City Item ball club 27–17 at the Athletics’ grounds at 17th and Columbia. A scheduled game against the white Masonic Club of Manayunk had no published results.

The Pythians appear to have been less active on the ball field over the next two years. There is no record of them playing in 1870, a development that may be explained by the larger issues demanding the attention of Catto and his prominent teammates.

In February 1870 Congress passed the 15th Amendment giving black men the right to vote. With enfranchisement Catto faced a whole new set of challenges. Organizing and coordinating the black vote took precedence over everything. Catto anticipated that the black electorate would be challenged by the entrenched Democratic leadership of Philadelphia. In the past the all-white police force had tolerated violence by fire and hose companies composed largely of Irish immigrants against the city’s blacks. With this history in mind, Catto and White knew it would be dangerous to invite black teams to their city and difficult to rent playing fields and attract spectators.

In 1871, the Pythians resumed a moderate playing schedule at the newly renovated National Association Athletics’ grounds at 25th and Jefferson. Only four games have records. The team’s sole defeat was at the hands of the powerful Unique baseball club of Chicago. They lost 19-7 but two days later avenged themselves by beating the Chicagoans 24–16. This victory appears to be last game played by the original Pythians.

The club’s prospects were not encouraging. Catto and many of his teammates were in their early 30s and had done little to recruit or nurture younger players. Additionally, Pythian members were engrossed by the political issues of the day. Catto did not actually participate in the 1871 games. Instead, he prepared for the October 10 election and spent a great deal of time in Washington. Philadelphia’s general election was scheduled less than a month after the final Unique game, with the mayor’s office and the city’s patronage system on the line. Catto understood what was at stake and knew that local ward bosses, like William McMullan of Moyamensing, were ready to square off against pro-Republican black voters on Election Day.

Catto’s fears were realized when violence against potential black voters began a few days preceding the election. By the afternoon of Election Day, two black men had been shot and killed and black voting lines had been attacked. That afternoon, as Catto headed home to help quell the violence, a white man shot him in the back. A second shot hit him in the heart. Catto died in a policeman’s arms near his own front steps at Eighth and South. He was 32 years of age. No one was ever convicted for this alleged assassination.

Octavius Catto’s funeral was on October 16. City offices and businesses closed out of respect. The procession was comparable to Lincoln’s cortege. Thousands of people, black and white, lined Broad Street to pay their respects to this martyred leader. No black person had ever been honored in this way. Catto was buried at the Mt. Lebanon Cemetery at 17th and Wolfe.

Catto was mourned as a social reformer and civil rights advocate. Some even acknowledged what he had done for baseball and its diversity. The pioneering Pythians missed their captain and his crusading spirit, and after his murder they lost the desire to compete. Individual former Pythians continued to play baseball, but the club that paved the way for organized black ball playing disbanded. It was not until 1886 and the formation of the National League of Colored Baseball that the Pythians name was restored to a new Philadelphia franchise. But lacking sufficient funding, the new Pythians and their league folded by June 1887. Though the Pythian name disappeared from baseball, black players continued to be attracted to the game. The roots of black baseball are as deep as those of the game itself. And for players from Octavius Catto to Jackie Robinson, baseball was much more than just a game.

Thank you for this well-researched article on Octavius Catto! Another issue is that the successor to the Institute for Colored Youth, Cheyney University, is in dire financial straits. Perhaps it will hold on and carry the torch for a VERY inspired and educated Octavius Catto who was cut down in his prime.

Thank you, Margaret Darby, for your enlightening and empowering comment.⚾️👨🏾🎓👊🏾❗️

Michael Coard, Esquire

1982 Cheyney University (then Cheyney State College) Alumnus