Stew’s semi-autobiographical rock musical, revived this month at Wilma Theater, follows a middle-class African-American youth on his journey through the European art scene in the 1980s. The script isn’t strong — the portraits of both cultures are cartoonishly exaggerated, the songs (created with Heidi Rodewald) are formulaic, the lyrics are repetitive and cliched — but the talent and unity of the cast make the experience worthwhile.

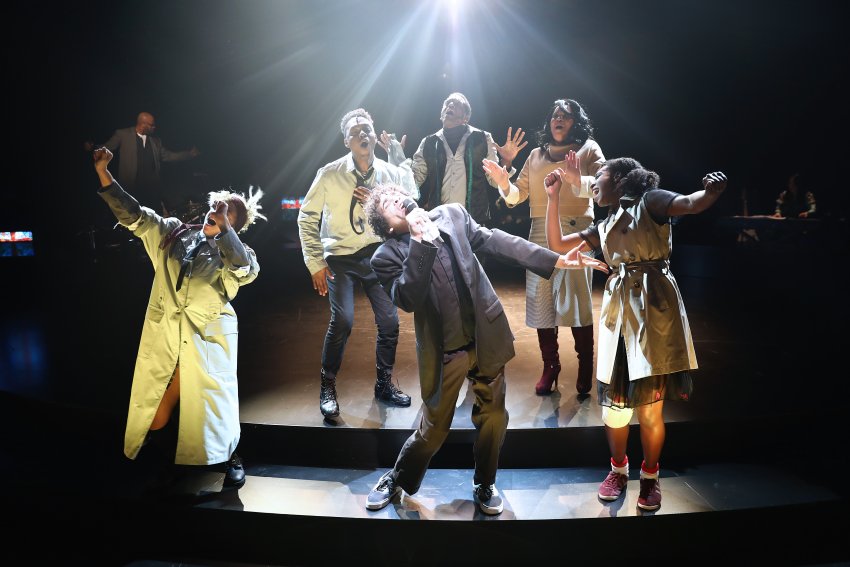

The band, led by Amanda Morton, is tight and works overtime, some songs barely ending before another begins. The stage is set with old televisions, fritzing like a dystopian 80s movie. Projections glow psychedelic scenery and laser airplanes, designed by Christopher Ash and Tal Yarden. Jamar Williams, as the Youth, plays best in front of the backdrop of the ensemble. They morph from childhood friends to sexy Hollanders to activist Germans with the help of inventive costumes by Vasilija Zivanic.

Lindsay Smiling is on point as the effeminate choir director who opens the window to the art world. Savannah L. Jackson is funny as a militant German pornographer, but we unfortunately only get a few moments of her gorgeous voice throughout the play. Taysha Marie Canales is strong as his life-changing love Desi but rolls her r’s in a very un-German way. Anthony Martinez-Riggs gets the juciest roll: Venus, the cabaret host. He is fully committed to being wild, happily screaming in his skirt and go-go boots. His expressive face is hilarious when he’s stoned in slow motion.

A dimmer talent would be outshined by Martinez-Briggs, but Jamar Williams blazes with the musical theater trifecta. He emanates the slouchy sulky teenager as comfortably as he does the invincible young man. His full vocal range goes from growling to ethereal in a second. He throws himself so fully into “Identity” that it becomes one of the more compelling songs, even though it’s meant to make fun of the avant-punk scene in Berlin. In “The Black One”, he puts on an uncomfortable, minstrel-like performance that highlights his mad dance chops. Not only does Williams get to burn at full brightness here, but it’s also where the play gets interesting. It starts asking a question instead of hurling cliches: can an African-American appropriate black culture? These songs seem to say yes and call out both the youth and the Europeans: him for assuming a “ghetto” identity, and them for exoticizing it.

The end of the play leans heavily on the narrator, played by Kris Coleman. Coleman is good, but after watching the star power of Williams, the energy dwindles. All the sappy motifs are repeated, “Love is more than real”, “Life is a movie starring you”. Mother (Kimberly Fairbanks) dies suddenly and dramatically, the day before her son returns. It’s fitting in a play that’s a caricature of life, and of art. Luckily, the performers are truly artists and leave a bright impression long after the lights go down.

[Wilma Theater, 265 S. Broad Street] January 10-February 18, 2018; wilmatheater.org.