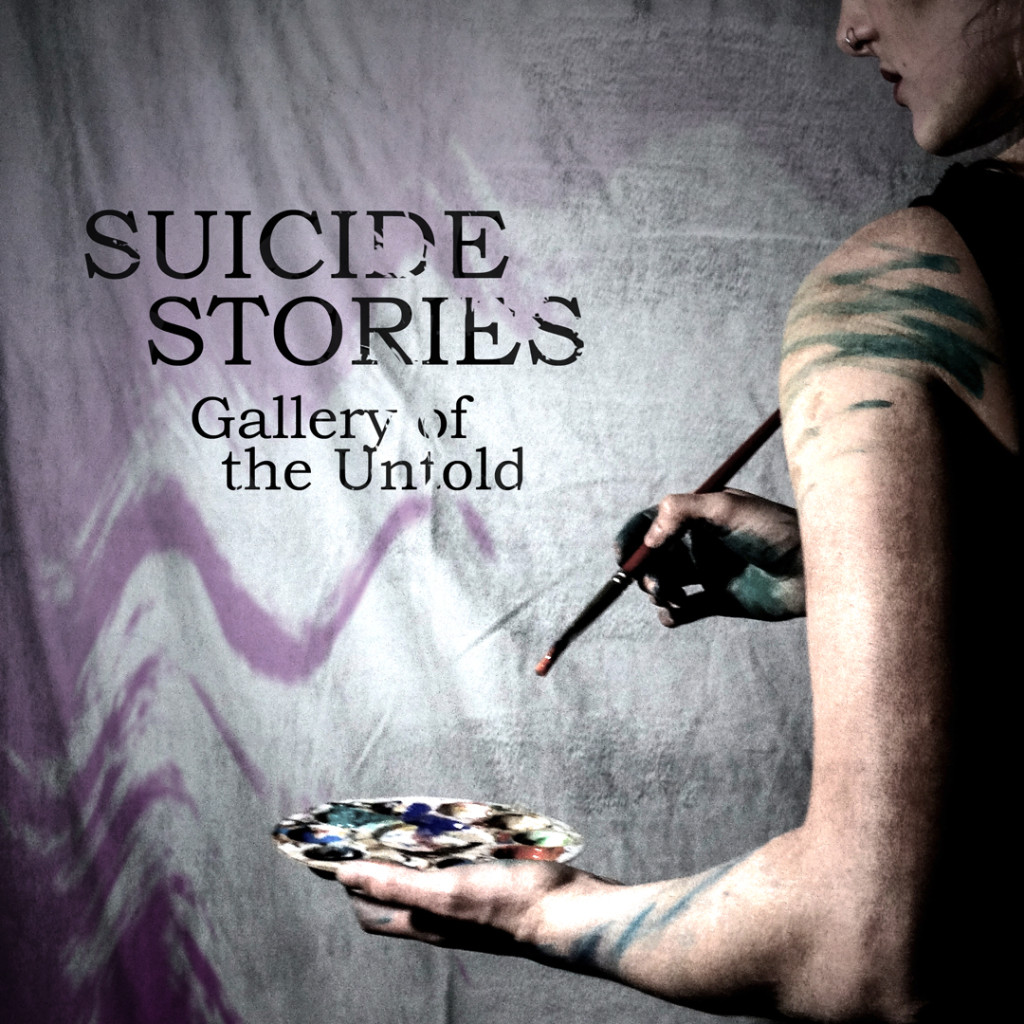

Society usually demands that we trod softly to avoid offending anyone. The subject of suicide is so taboo that few playwrights tackle the topic, and even fewer theater companies present a whole evening of plays about suicide. Elephant Room Productions (ERP), well-known for its courage to address difficult issues, enlisted nine playwrights from Philadelphia and all over the U.S. The ERP team, known by the playwrights as “The Herd,” worked together with each playwright over an extended period of time to develop each play individually. As a result, ERP will present Suicide Stories: Gallery of the Untold as part of the Philadelphia Fringe Festival, September 12–16 at 6 pm and 8 pm at the Asian Arts Initiative at 1219 Vine Street, Philadelphia, PA. For tickets call,215-413-1318, or purchase them online.

Society usually demands that we trod softly to avoid offending anyone. The subject of suicide is so taboo that few playwrights tackle the topic, and even fewer theater companies present a whole evening of plays about suicide. Elephant Room Productions (ERP), well-known for its courage to address difficult issues, enlisted nine playwrights from Philadelphia and all over the U.S. The ERP team, known by the playwrights as “The Herd,” worked together with each playwright over an extended period of time to develop each play individually. As a result, ERP will present Suicide Stories: Gallery of the Untold as part of the Philadelphia Fringe Festival, September 12–16 at 6 pm and 8 pm at the Asian Arts Initiative at 1219 Vine Street, Philadelphia, PA. For tickets call,215-413-1318, or purchase them online.

In this interview, the nine playwrights talk openly about the difficulties and the joys of working on a sensitive subject in a collaborative way:

- Daryl Banner (Texas) – The Problem with Mickey

- Brittany Brewer (Philadelphia) – Casual Rape

- Brian Grace-Duff (Philadelphia) – I Forget What Eight Was For

- Dano Madden (New Jersey) – Jason Dotson

- David Meyers (California) – Broken

- Bridget Mundy (NYC) – Dark Windows

- Christopher G. Ulloth (NYC) – Museum Bar

- Kevin White (Philadelphia) – Rob

- Kat Wilson (Philadelphia) – The SS Marty

Henrik Eger: Even talking about suicide can be difficult for many people, let alone writing a play about it.

Dano Madden: I felt a bit hesitant about suicide as a theme for an evening of theatre. It is a taboo as part of the topic in America, but it needs to be brought more to the forefront of people’s minds. However, to build an evening of theatre around it risks being very heavy-handed. My approach in writing Jason Dotson was to try and write about my personal experience with suicide in a way that would be surprising and engaging to audiences without slipping too far into the darkness.

Brian Grace-Duff: It took me a long time to agree to write a scene for this play because I knew, based on the subject matter, that it would be a more personal process for me. When I laid out a proposal for I Forget What Eight Was For, I was a bit nervous. Yet, I was thrilled when ERP [Elephant room Productions] responded with an enthusiastic “yes.” I worked through several drafts and had some really wonderful advice from both ERP through their EERS [Elephant Ears Reading Series], as well as some trusted friends.

Henrik Eger: Did you know right away what you wanted to say? If not, tell us about the evolution of your play.

Brittany Brewer: My piece, Casual Rape, was inspired by a slam poem I wrote and performed for ERP’s A Midsummer Night’s Cabaret.

David Meyers: Broken is actually an adaptation of a full-length play that we workshopped in New York. Elephant Room was generous enough to commission a shorter version.

Kevin White: When Elephant Room Productions reached out to me about this project, I was interested but didn’t have a set direction I wanted to go. Lauren and her team suggested a variety of topics to write about and cyberbullying stood out to me. From there, I found true stories of suicides caused by what’s known as catfishing [“to lure someone into a relationship by means of a fictional online persona”], which led me to the finished product, Rob.

Henrik Eger: Family relationships can play an important role—for better or worse.

Chris Ulloth: Writing about my sister and her death started as a way of coping and processing. It has since become a large part of my work. This piece, Museum Bar, in particular, built upon a play I wrote earlier.

Bridget Mundy: I always go to my memories, my own stories, and pull from there. Some of these things in Dark Windows have been based on interactions with my father. I used our connection to understand how to create Erin’s [relationship] with her father.

Henrik Eger: Society usually demands that we trod softly to avoid offending anyone.

Daryl Banner: I wanted to approach the subject of suicide from an uncomfortable place, because it bothers me when I see depression and suicide get glorified or used as plot-moving tools in TV shows and movies. Coming at the subject of suicide from the bully’s perspective in The Problem with Mickey gave me the ability to hit suicide, depression, and gay bullying with a more blunt and unapologetic voice.

Since I grew up as a gay teen myself, I was able to antagonize myself in a creative way through the bully’s eyes, and find a common ground upon which sympathy and understanding could be paved. “Love thine enemy”—and all that. The trouble is figuring out what the enemy is. The bully? The bully’s friends? The bully’s parents? Society? Our own psychology?

Maybe the nature of suicide and bullying is far more complex and deeply rooted than we realize.

Henrik Eger: I understand that you were inspired to write this play by something that few human beings experience.

Kat Wilson: The SS Marty came to me in a vivid dream. I used my synaesthesia [“a perceptual phenomenon in which stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway leads to automatic, involuntary experiences in a second sensory or cognitive pathway”] to push the story forward—attaching a story line and characters to the colors I felt. I also received a great deal of help from US veterans whose insight give this play legitimacy and heart.

Henrik Eger: Looking back as a playwright, what were the greatest insights you gained from writing about this play in a collaborative way?

Brian Grace-Duff: Most of my writing is highly collaborative. In many ways, the challenge of this process has been to step back and let the words stand on their own, but that’s been made a lot easier by having a really talented team to work with.

Kevin White: Having “The Herd” (ERP staff) read my script out loud and give me recorded feedback was really helpful. It was great to be able to hear different drafts of my words out loud and be able to compare recordings throughout my process. It was also helpful to find my many grammatical errors within the piece.

Henrik Eger: Each of you comes with different experiences and perceptions. What did you learn from your collaborative feedback sessions with the ERP team, and how did their feedback impact your play?

Kat Wilson: I was able to hear my words through different voices, both literally and figuratively. Between veterans, actors, my colleagues, and my friends—the feedback I received constantly allowed me to think more creatively and progressively.

Daryl Banner: Actors love the word “f**k” and all its tasty variants. However, I greatly reduced the number of F-bombs throughout my piece so that the actor would understand that it is not meant to be read angrily from one end to the other.

Henrik Eger: Writing can be a lonely and challenging activity, especially when dealing with depressive subjects. What were your experiences with the collaborative ERP approach?

Bridget Mundy: To take something people still won’t talk about and ask [them] to open that door—it was amazing to see how each writer approached it. Everyone had a different way of knocking on the door.

David Meyers: My favorite part of being a writer is the collaboration. I hate the act of writing because it forces me to be alone.

Dano Madden: I am based in the New York City region, so my collaboration has been from a distance. The team at ERP sent me feedback and recordings of my play being read. All of this has been helpful, but I would have preferred to be in the room with the actors and director.

Henrik Eger: ERP works with young writers and experienced professionals.

BrittanBrewery : As a young playwright, I always find it valuable when others take the time to read my work and ask questions. This process has affirmed my interest to continue to seek out collaborative opportunities to create work and playwrite.

Chris Ulloth: This piece received much more attention than my previously written works on this topic. In addition to the three readings it had internally with ERP, there was a considerable amount of one-on-one with the director. Even for a professional, this is not an easy thing to do when the topic is so personal. It takes working with a team you trust and respect, and it takes time. It wouldn’t have been possible without everyone on the team being patient with me as we figured out the best way to execute this piece.

[Asian Arts Initiative, 1219 Vine Street] September 12-16, 2017; fringearts.com/event/suicide-stories-gallery-untold/

Running time: Two hours with no intermission. Come and go as you please.

One Reply to “Even Talking about Suicide Is Difficult: Nine playwrights on collaborative playwriting with Elephant Room Productions”