Author’s note: Taylor Mac uses “judy” as a gender pronoun. This review reflects Mac’s preference.

Taylor Mac’s work is unwieldy and absurdist, challenging and unsettling. These elements often work to judy’s advantage, as in the epic The Lily’s Revenge or A 24-Decade History of Popular Music, which was a finalist for this year’s Pulitzer Prize in Drama. Those works intentionally upend what we expect from a theatrical experience, causing those in the audience to question their relationship to and expectations of narrative, entertainment, and culture writ large. Mac’s HIR, currently receiving its Philadelphia premiere from Simpatico Theatre, has similar goals; unfortunately, Mac’s decision to take a more traditional storytelling approach accentuates flaws in judy’s craft that might not seem so obvious in judy’s larger, more freewheeling works.

At its essence, HIR is a riff on the classic kitchen-sink drama, sprinkled through with a fair amount of influences: the absurdism of Ionesco and Beckett (the play’s published script cheekily calls the genre “absurd realism”); the overtly political theater of the 1950s and 1960s; the gender- and genre-bending works of Charles Ludlam; and the coexisting grittiness and humor of working-class sitcoms like Roseanne or Married with Children. Mac husbands these disparate styles together to examine both the crumbling ethos of the “traditional” American family and the widening scope of gender identity, humorously satirizing the acronym-obsessed “LGBTTSQQIAA” (pronounce “Lug-A-Butt-Squee-Ah”) community.

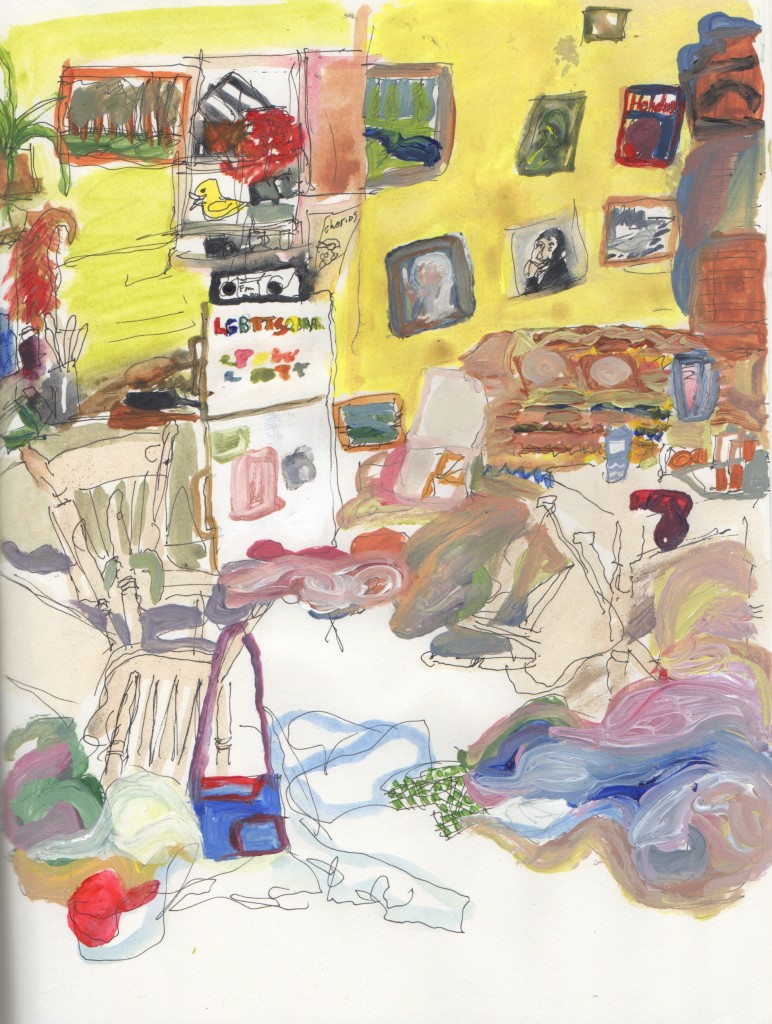

The play’s more outré elements are often the most arresting, and director Jarrod Markman handles them well. Upon walking into the Louis Bluver Theatre at the Drake, we are greeted by a world quite literally turned upside down: the stage setting of an unremarkable suburban house is strewn with piles of laundry, dirty dishes, and haphazardly hung art. (Designer Christopher Haig perfectly captures Mac’s script note that this is “the kind of home that, no matter how hard you clean, will always seem dirty.”) The outward chaos is a manifestation of liberation for Paige (Marcia Saunders), the formerly put-upon housewife who wrested control of the family after her abusive husband, Arnold (John Morrison, who conveys much through little dialogue), suffered a stroke. Arnold is now a parody of a patriarch, costumed in full makeup, a pink nightgown, an adult diaper, and a Dolly Parton wig. “It’s what we do now,” Paige tells her mortified son, Isaac (Kevin Meehan), who returns home from gruesome duty in an unnamed war. “We play dress-up.”

Paige has spent the majority of her life caring for her family while cowering in fear of her husband. Now that she’s in charge, she’s instituted a new world order. She has lovingly embraces her transgender son, Max (Eppchez!), whose preferred gender marker gives the play its title (it is pronounced “here”), and longs for Isaac to join their merry band of gender outlaws. This sets up the play’s primary conflict: Isaac becomes an avatar of the old guard, unwilling to cast aside his hateful father and all he represented in favor of the new freedoms espoused by his mother and brother. Family dramas are built around such clashes of old and new, and Mac’s story has the bones of a fascinating exploration of how too many freedoms may bring about the same level of unhappiness as too much constriction.

Unfortunately, much of HIR feels like an extended metaphor rather than an actual blood-and-guts play. An intelligent audience member can sniff out where the play is heading about five minutes in, which still leaves two remaining hours that need to be filled. In the service of his grander points, Mac sacrifices character development; his family unit is a rehashing of familiar tropes disguised as a deconstruction of them. There is little variation in Paige (Roseanne Barr crossed with Mother Courage) or Isaac (the dutiful son who cannot help but empathize with his abuser), and the performances of Saunders and Meehan suffer for it. Not even Max—who seems refreshingly free of artifice in the early scenes, so wonderfully authentic—escapes without falling victim to some level of schmaltzy stereotype. It is a credit to Eppchez!, this production’s unquestionable find, that the character’s welcome doesn’t wear out entirely.

Like most political artists, Mac’s messages are big as billboards, worn on the characters’ sleeves. But he lacks the narrative skill of a Brecht, Baraka, or early Albee, so much of the play feels like it is simply skating from one grand point to the next. The war in which Isaac fought should be a key plot point throughout, as should Isaac’s role within it: A member of the “mortuary affairs unit,” he was tasked with clearing the body parts of obliterated soldiers and civilians. Yet Mac jettisons it most of the time, only to trot it out in an attempt at chilling denouement. This and other late developments suffer because they seem both obvious and disconnected—they feel more like mere statements of fact than disquieting revelations.

HIR makes a lot of noise but not much of a point. Mac may be a visionary in the most literal sense of the word, but judy has not yet learned how to make an extraordinary/ordinary family like the one presented here feel like they’re flesh and blood. In the end, that does a disservice to the important conversations judy’s work aims to generate.

[Louis Bluver Theatre at the Drake, 341 S. Hicks Street, Philadelphia]; May 31-June 25, 2017; simpaticotheatre.org.

Max is Paige’s “transgender child” not son Isaac’s “sibling” not brother. It is so rare and important to have non-binary representations in art please help to celebrate this by not forcing the character of Max back into a binary that does not serve hir.