“FUCK THE KING! BEAUTY SHALL LIVE!” And there you have the essence of the debate—obedience vs. imagination, authority vs. curiosity—central to Rajiv Joseph’s absorbing new play, GUARDS AT THE TAJ. But unlike most debates, political or aesthetic, this isn’t just talk: when you lose this one, you really lose. And, come to think of it, the same debate is central to the Book of Genesis—a problem Rajiv Joseph worked on in his earlier play, The Bengal Tiger in the Baghdad Zoo. And, come to think again, Genesis is a pretty high stakes situation, too.

GUARDS AT THE TAJ begins with two guys, best friends since childhood, standing, gleaming swords in hand, with their backs to the walls that for sixteen years have hidden the construction of the just-completed Taj Mahal. No one but the 20,000 workers who built the great monument to the dead empress has seen it. The big reveal will come at first light, in that one moment of perfection before anything—rain or dust or gazes—has sullied the magnificent building, the most perfect example of man-created beauty.

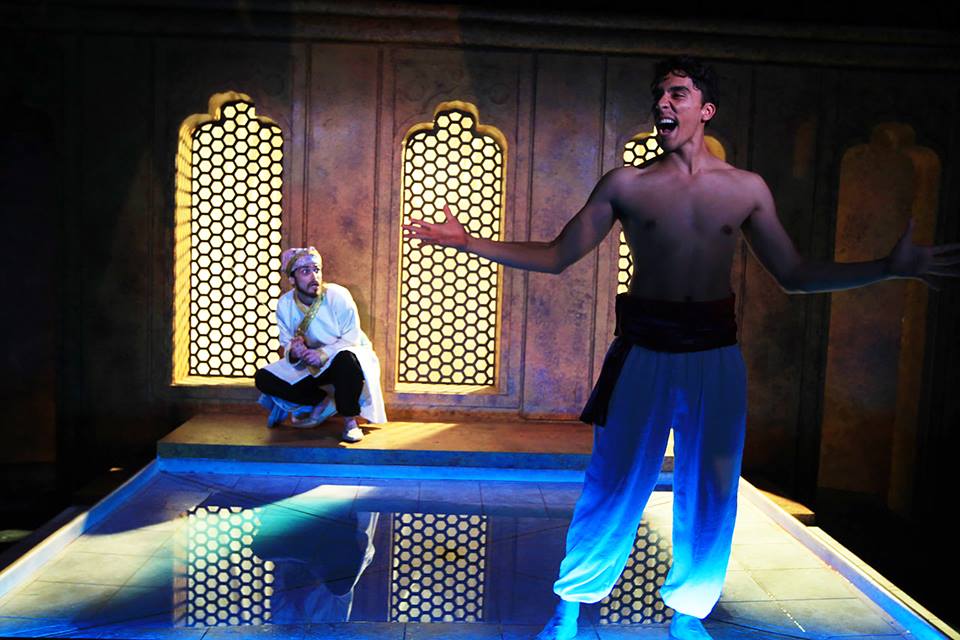

Each of the two men is a study in contradictions: Humayun (Anthony Mustafa Adair) is the rules-and-regulations man, who deeply believes in authority—Allah’s, the Emperor’s, the elders’, his father’s. But he also loves birds and can identify them by their calls. Babur (Jenson Titus Lavallee) is that guy, the messy one who’s always late, but who has an instinct for wonder, and is dazzled by the stars. Their playful imaginations invent the impossible: flying machines and transportable escape holes.

The actors are terrific, managing to contain the astonishing brutality of the plot (no spoilers) in the quirky, talky script. Both Adair and Lavallee grab hold of the crucial anachronistic need to seem absolutely contemporary in speech and manner while still conveying the 17th century exoticism of their time and place.

But it’s the bizarre style of the show more than the content that’s the point, a style you could call slapstick gore. Think Martin McDonagh. And then think Alfred Hitchcock. Deborah Block’s direction makes much of the play’s gruesome demands (much credit to props master Flora Vassar), although Block—or perhaps the limitations of Studio X—seems to have shortchanged the visual magical effects; the lighting (Drew Billiau) lacks the enchantment the stage directions require. The sound design, however, is a knockout: like the play, it’s scary and funny and profound all at once.

All told, this production is not for the fainthearted. Nor for the squeamish. But definitely for those interested in contemporary theater and in one of its smart, compelling new voices.

[Theatre Exile at Studio X, 1340 S. 13th Street] October 20-November 13, 2016; theatreexile.org.