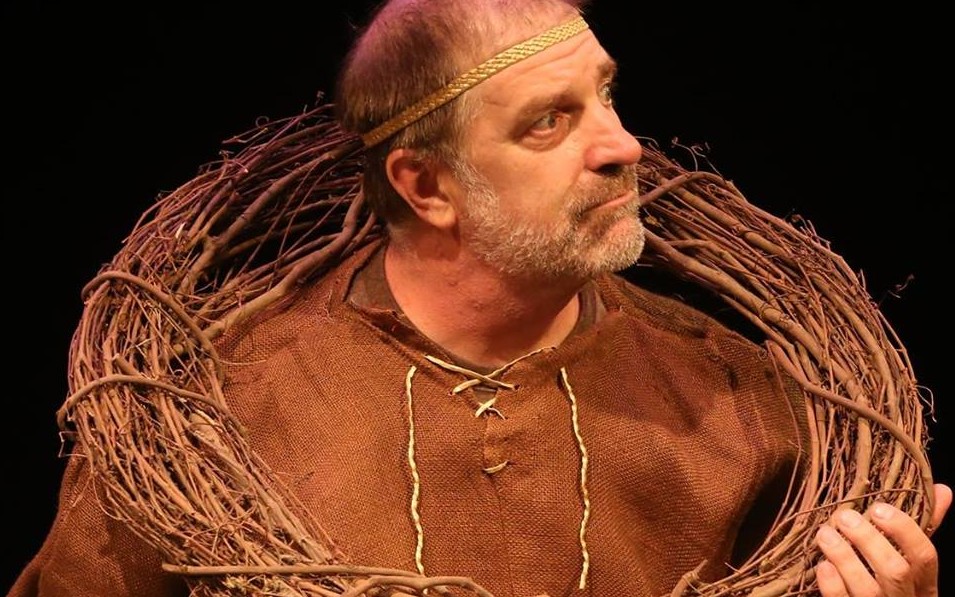

Henry II is worried about the future: his wife and eldest son Richard have revolted against him, France wants their land back, and his mistress is engaged to his incompetent heir Prince John. At the ripe old age of 50 he fears for his legacy. This is funny because we know Henry (John Lopes) is the first Plantagenet king of England, and his offspring will rule the land for the next 300 years.

Henry II is worried about the future: his wife and eldest son Richard have revolted against him, France wants their land back, and his mistress is engaged to his incompetent heir Prince John. At the ripe old age of 50 he fears for his legacy. This is funny because we know Henry (John Lopes) is the first Plantagenet king of England, and his offspring will rule the land for the next 300 years.

This duality of being in a time and looking back on that time is well synthesized in the play. The tunics are medieval but the jeans are casual Friday. The curtain call is a Gregorian chant set to a techno beat. The jokes are temporally tongue-in-cheek:

John: He’s got a knife.

Eleanor: Of course he has a knife! He always has a knife. We all have knives! It’s 1183 and we’re barbarians!

And so the vibe alternates between Shakespeare and family sit-com. Most of the cast chooses one or the other. The neglected middle child, Geoffrey (Robert DaPonte) is a scheming Iago in training. Harry Watermeier’s Prince John is a spoiled brat, all his jokes deserving of a laugh track. David Pica is solemn and serious as Richard the Lionheart. But, somehow, Megan Bellwoar has figured out the quantum mechanics of existing in both places at once. Her Eleanor, Queen England, wife and prisoner of Henry, has both the fluid grace of a powerful ruler and the wry, self-aware sadness of a woman cast aside from her family (“I can’t touch my sons but in scenes”). Watching her spar with Henry is a delight. In the chess game of promoting their favorite sons, each is devastated by the other’s unexpected blows but admire -and are a little turned on by- their spouse’s cunning. We wish Mom and Dad would get back together.

Sadly, it’s not meant to be. It’s Christmas time, but the tree is bare. They hang holly branches around the spare setting, but there are no leaves or berries. Henry is having an affair with Alais (Lena Muchetti), his ward and bridal pawn. Richard, is having an affair with King Phillip of France. Andrew Carroll, playing the sharp, smart Philip, argues with Henry, revealing that the relationship with Richard was originally more like rape than love. This family is ripping itself apart, and Henry is right to be worried about his legacy, but the actors aren’t given a chance to get into this lower, darker part of themselves. Lopes sympathetically smoothes over how creepy it is to be sleeping with his step-daughter, and Pica’s gentle smiles at Philip give no hint of domination.

Because they are unable to dive deep into these parts of their character, the moments of high tension are less than dynamic. Thankfully, the comedy is so well played the high drama isn’t sorely missed. It’s more about the witty dialogue, of which there is plenty, and the graceful machinations of Eleanor: the master tapestry weaver who holds the family and the play together.

[Black Box Theater. 3401 Filbert Street] August 11-27, 2016; commonwealthclassictheatre.org.