The characters in Nikolai Gogol’s The Government Inspector lack love and sympathy for others. It’s this absence of empathy among members of the ruling class and their irresponsibility, corruption, and unwillingness to take positive action which led to protests by Russian conservatives in the reactionary press when it was first produced.

Gogol had become famous through his short stories. He abandoned his first few plays, fearing censorship of the ruling class. In 1835, he asked his friend Pushkin to send him an idea of something very Russian that Gogol wanted to turn into a satirical play. “My hand is itching to write a comedy. . . . Give me a subject and I’ll knock off a comedy in five acts — I promise, funnier than hell. For God’s sake, do it. My mind and stomach are both famished.”

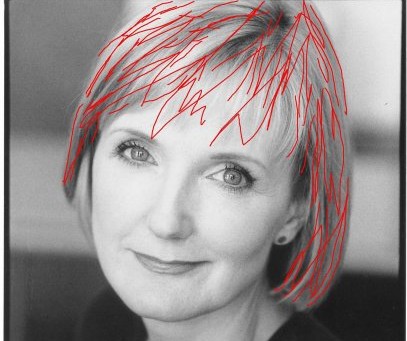

In this two-part interview, Idiopathic Ridiculopathy Consortium (IRC) director Tina Brock shares facts and her insights on Gogol’s unique showcase of despicable government officials.

[Walnut Street Theatre Studio 5, 825 Walnut Street, 5th floor] February 2-28, 2016; idiopathicridiculopathyconsortium.org.

Henrik Eger: Tell us a bit about the philosophy of the Idiopathic Ridiculopathy Consortium [IRC], Philadelphia’s popular theater of the surreal, and how it relates to The Government Inspector by Gogol.

Tina Brock: The IRC mission statement reads, “producing and presenting plays that explore and illuminate the human purpose . . .”—with an emphasis on examining our spiritual connection to the world, and those we have relationships with, and how our philosophies, beliefs, and ideals influence the decisions we make. Particularly in Inspector, the ways in which we jump to conclusions about people, make assumptions without the benefit of enough information, and how those judgements may have disastrous consequences, spreading like a wildfire into the community.

Eger: As the IRC director, what intrigued you about Gogol’s The Government Inspector?

Brock: These questions prompted me to tackle this play: Why do we fail to ask enough questions of people in lieu of or in addition to accepting the stories they tell of themselves? It seems it takes much longer to come to know a person’s character given social media. Inspector was written nearly 200 years ago, when the delivery of a letter bearing crucial news took days to arrive. Perhaps people were so excited to receive news, the idea of questioning the messenger was secondary to the event of receiving. Today, information is exchanged so rapidly, it seems the task of stopping to think about the message, the messenger, and the context has been lost by the wayside. With ever more paths of information with many messengers in the mix, taking time to raise pointed questions when necessary is a necessity in order to try and make sense of it all.

The investment of time in getting to know people long enough to see their behaviors over the course of time, to experience and watch the decisions that shape their character, and to allow the chance to evaluate content in addition to presentation is a task that takes time. When fear enters into the equation, when people in positions of power become afraid of losing their interests, then anxiety fuels the proceedings and the act of questioning, contemplating, and verifying before passing along the fear baton is lost. Farce ensues and we’re off and running in an absurd situation. We see it every day.

The Inspector plot centers on two town gossips, Bobchinsky and Dobchinsky, who spend all of their time traveling from the Inn to the Market where they sell the meat pies and French Brandy Kegs, excited about the latest piece of information they can pass along to the townspeople. They make it an art to be the first to have the information and squabble over who is the first to deliver, who can get the details right when telling the story. They push each other to be first to share the news. It is based on Bobchinsky’s observations that the new young man in town, Khlestakov, is indeed the government inspector, based on some shaky observations. The townspeople buy his gossip, don’t ask a single question, and the wildfire has been ignited.

Eger: Given IRC’s philosophy, how easy or difficult is it to find plays that are truly surreal and yet speak to us in our own time?

It’s easy to find works that speak to the existential dilemma of reconciling man’s desire to be omnipotent, with the fact that we have limited time to find our purpose and to create meaning in what we do. Playwrights Ionesco and Beckett address the existential crisis head on, allowing the audience to rest in the crisis through feeling, requiring you to submerge in the angst and also, hopefully, the humor.

Eger: You have consistently featured international playwrights, this time Gogol, a Russian Ukrainian. What made his work stand out for you?

Brock: His writing is hilarious. He has a beautiful understanding of human behavior and how our fears drive us to extreme circumstances and how chaos results. Gogol asks that we jump on the locomotive, hold on tight, and go along for the ride, realizing the preposterous chain of events that a simple set of assumptions can ignite. The difference in Gogol’s work from the later absurdist authors is that we don’t light on that existential feeling during the course of the play as we do in Beckett or Ionesco; rather, we expose the folly and the ridiculous situations that create the farce.

The existential questions raised in plays by absurdist authors are particularly potent and resonating with audiences, they are timeless. Perhaps because world events are so hard to fathom, atrocities so great, audiences seem keenly interested in looking inside, celebrating and examining those questions: how can I bring more meaning to what I do? How do my choices affect those around me? So there’s the personal aspect, the looking inside and asking how we can contribute in a more meaningful way, and there’s the system outside ourselves and how we affect that process. The political system has become a circus side show. How do our differences in politics and beliefs lead to such disastrous consequences, and how much healing might happen if people were to take the time to have a conversation and listen with the intent of understanding, not judging, and hold each other and our leaders accountable without being branded troublemakers. As Ionesco said, “It’s not the answer that enlightens, but the question.”

Eger: We are going into the presidential election this year with a lot of angry people: Republicans who believe that it’s all the fault of “the government,” while Democrats tend to blame the greed and corruption of the corporate world. How do you connect your production of The Government Inspector to these deeply seated fears in the US?

Brock: People are angry because their voices aren’t being heard. They are tired of being marginalized, tired of being told they don’t know what they are talking about, and they don’t have the intelligence or understanding to propose solutions to simple and complex problems. We are all people. We live, work, eat, play, have ideas how to solve life’s dilemmas—and try to solve problems. You don’t have to be a specialist in any discipline to propose a solution or be in charge of change. People need to ask questions and leaders need to provide answers or admit they don’t know the answer. And we need to get over the social stigma that can go along with demanding straight clear answers and accountability. It’s the accountability piece that’s very distressing. Certain people in society, because of rank, privilege, and order, have an automatic hall pass to do whatever they please in the name of advancing their particular agenda.

Another great interview, Henrik. Tina is one of our great treasures here in our community and always presents challenging, thought provoking and just plain tremendously fine work.