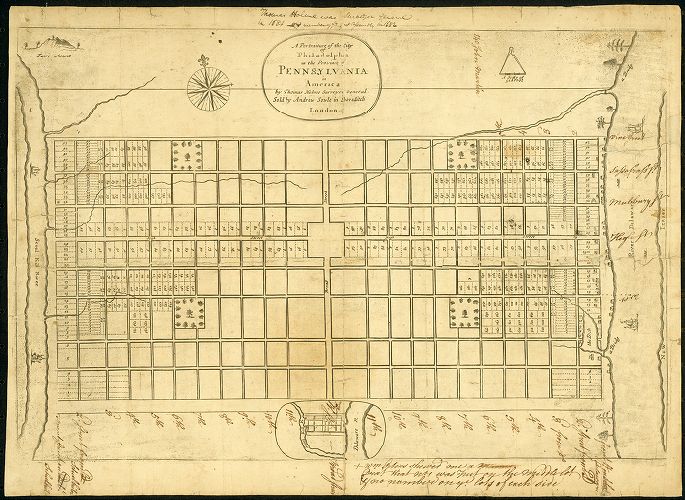

The city (as the model shows) consists of a large Front Street to each river, and a High Street (near the middle) from front (or river) to front, of one hundred foot broad, and a Broad street in the middle of the city, from side to side, of the like breadth. In the center of the city is a square of ten acres… There are also in each quarter of the city a square of eight acres … and eight streets (besides the High Street) that run from front to front, and twenty streets (besides the Broad Street) that run across the city, from side to side; all these streets are of fifty foot breadth.—“Portraiture of the City of Philadelphia” (1683), by Thomas Holme, Library Company of Philadelphia

In 1681, King James II granted William Penn a large tract of land in North America to settle debts to his family and provide a new colony for his troublesome and persecuted religious cohort the Society of Friends, or Quakers. The following year, Penn sailed to inspect the extensive landholding and to found the town that would form the core of his “Holy Experiment” of a tolerant political utopia: Philadelphia.

Choosing a two-mile-long path of dry land just upstream of the confluence of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, where the rivers’ courses briefly approach each other again, Penn set about designing his new settlement. In 1683, he published a map of the city to attract settlers from England (quoted above). Although it represented his ideal for the city rather than a realized fully metropolis, the map Penn published would be largely recognizable to modern-day Philadelphians.

English cities at the time were an unplanned maze of old horse tracks and small holdings, and early settlements in North America followed this pattern—visit central Boston or Lower Manhattan today and you will still see a hodgepodge of winding and diagonal streets. Penn’s map of Philadelphia saw the first iteration of the classic American street design: the simple to navigate grid.

Penn hoped to create a “Green Country Town,” with wide orderly streets free of the overcrowding, fire, and disease which plagued European cities. Central to this idea was his inclusion in the design of five public squares, one in each quadrant of the city and one in the center. Though they have seen changes in form and function, these scenic urban parks remain inviting features of this bustling modern city.

Southwest (Rittenhouse) Square

Penn’s plan called for a rectangular town spread east to west from river to river in the area we call Center City. In its early days, however, Philadelphia grew north-south along the banks of the larger Delaware River and the area west of Broad Street was for many years sparsely populated hinterland.

The scene is very different today. Rittenhouse Square is perhaps the most vibrant outdoor space in Philadelphia. Originally called Southwest Square, the park was renamed after David Rittenhouse, a renowned astronomer and the first head of the United States Mint. Surrounded by luxury high-rises, active cultural spaces (the Art Alliance, the Curtis Institute of Music, and the Ethical Society, among others), and some of the best al fresco dining options in Philadelphia, Rittenhouse Square also gives its name to one of the city’s liveliest and loveliest neighborhoods. Visitors can admire stately Victorian homes on the surrounding blocks, enjoy upscale shopping options along Walnut Street, and wile away pleasant hours people watching on a park bench or the tree-shaded grass.

Southeast (Washington) Square

Less bustling but nearly as picturesque, Washington Square (named after President George Washington) forms part of Independence National Historic Park. This contiguous series of open space also contains Independence Hall, the Liberty Bell Center, and other key sites from the founding of the United States.

But while world historical events occurred just a few blocks away, old Southeast Square enjoyed a quieter life. Used as a grazing ground for livestock, the square was also a burial ground for poorer Philadelphians, British and American soldiers of the Revolutionary War, and victims of the Yellow Fever epidemic which decimated the city in 1793. An untold number of bodies still lie beneath the park’s grass, making the square a haunting stop of the popular Philadelphia Ghost Tours. In 1954, remains of one of the Revolutionary War dead were disinterred and reconsecrated in the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, a poignant monument to those who died in the War of Independence.

The square is bordered to the north by the Curtis Building, formerly home to the publisher of the Ladies Home Journal and the Saturday Evening Post. The lobby is worth a visit today for the impressive “Dream Garden” glass mosaic, commissioned by the Curtis Publishing Company from the famous Louis C. Tiffany studios and based on a painting by Philadelphia artist Maxfield Parrish.

Northwest Square (Logan Circle)

A visitor to Philadelphia today trying to navigate the city using Penn’s 1683 map would be struck by one key difference: the Ben Franklin Parkway. A wide scenic boulevard which cuts diagonally across northwest center city from Love Park to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Parkway is home to many of Philadelphia’s most impressive sights, including the Free Library, the Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul, the Franklin Institute, the Academy of Natural Sciences, and the Barnes Foundation. In the middle of this boulevard is a circular park with views of all these architectural delights: Logan Circle.

Once a burial ground and site of public executions, Northwest Square took its present shape when the Parkway was carved out in the 1910s. This open outdoor space now contains Philadelphia’s most famous water feature, Swann Fountain. Its beautiful bronze statues represent the three main waterways of the city (the Schuylkill, Delaware, and Wissahickon). They were sculpted by Alexander Stirling Calder, a fact which provides an intriguing centerpiece to the Parkway. Calder’s father (Alexander Milne Calder) designed the William Penn statue on City Hall at one end of the boulevard and his son (Alexander “Sandy” Calder) was a pop art sculptor whose iconic mobile hangs in the lobby of Philadelphia Museum of Art at the other.

Northeast (Franklin) Square

Renamed after Philadelphia’s favorite son, Franklin Square was apocryphally the site of Ben Franklin’s famous kite and key experiment. Part of Philadelphia’s finest neighborhood in the 19th century, the construction of the neighboring Benjamin Franklin Bridge in the 1920s left the square isolated and run-down. Narrowly saved from demolition during the construction of I-676 in the 1980s, the park lay disregarded in the shadow of the bridge on-ramp until a major remodeling in the last decade saw it revitalized. Today it stands as a testament to Philadelphia’s regeneration—a key visitor attraction with a Philadelphia-themed miniature golf course, historic merry-go-round and fountain, two playgrounds, and a surprisingly tasty hamburger stand close to Independence National Historic Park.

.Centre Square (City Hall)

Situated at the intersection of Philadelphia’s two main thoroughfares, Broad and Market streets, Centre Square is the only one of the five original squares no longer solely a public space. Previously the site of an elegantly designed water works—part of one of the nation’s first urban water systems—Centre Square is now home Philadelphia’s City Hall. Constructed from 1871 to 1901, City Hall is modeled on the structure of Paris’s Louvre, a grand medieval palace cum art museum, and updated in the ostentatious architectural style of the French Second Empire. Supported by walls 27-feet thick at their base, it is the tallest free standing masonry structure and perhaps the largest municipal building in the world.

Atop its central tower stands a 37-foot-tall statue of William Penn gazing over the city he founded, with an observation deck below. For many years, Penn literally towered over the city he did so much to create: a gentleman’s agreement not to erect any building taller than the brim of Penn’s hat held until the construction of Liberty One Tower in 1985. Penn’s bronze visage is now shadowed by a twenty-first century cityscape of skyscrapers, but his influence looms ever large: just look at any city map.

Previously published in the Where Philadelphia Guestbook.

2 Replies to “The City That Penn Built”