The whistling of birds, water bubbling from fountain spouts to clap and splatter on stone, and the Doppler drone of bees wavering among the bobbing flowers: these images saturate the imagination when wandering the collection of painted flowers in The Artist’s Garden, an exhibit of American Impressionism on display at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

As we all wait for the weather to defrost our winter-weary bones, a grand panorama of summer awaits the active imagination to give it life. There, one can soothe the last dredges of winter depression, as well as simultaneously peer into an era where women were first gaining traction.

The Art of Blotting

American Impressionism swept into a flurry in the late 19th century, clutching at the shirttails of the French impressionist style that captivated Europe with its bold brushstrokes and almost abstract renditions of nature. Artists spent time in Paris to learn the technique, then would return to America, laden with desires to capture the essence of their own home gardens à la Monet.

Once the 1900s trundled in, impressionism had been molded and shaped by American artists into something distinct. The Garden Movement was a subset that expanded to rebel against the overwhelming changes happening during the Progressive Era — women’s suffrage, industrialism, and a rapid increase in immigration. Through gentle depictions of flowers and ladies in white dresses sipping tea at noontime, the perfect American middle-class idyll was perfected.

Despite this effort to represent a society unchanged by uncertainty, however, social progress had a way of creeping in. Women were still met with disdain in most professional spheres, but through the garden some found a path to betterment.

The Traditional Lady in the Garden

Women were the sole caretakers of the home, and so were also the curators of the household gardens. While the suburban men trekked to the loud, pollution-fogged cities for work, the women kept the home and presented themselves as part of the package, house and wife both a serene balm after a workday.

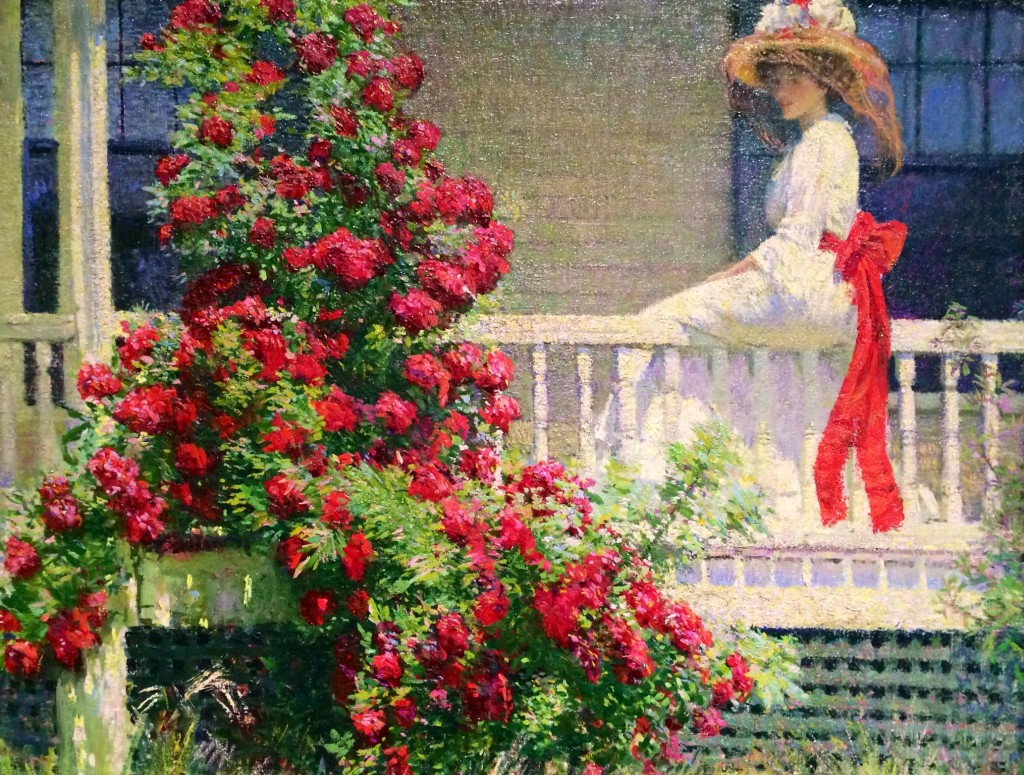

Some painters captured this on the canvas: the woman an ornament among the flowers, straight-backed like the hollyhocks, cheeks pink as a rose. In The Crimson Rambler by Philip Leslie Hale, a lady (Rose Zeffler, an often-employed model) smiles demurely from her perch on the porch banister, the ribbon of her dress the exact ruby hue of the flowers she poses beside.

In The Goldfish Window, Childe Hassam painted a woman in a room looking out into a vivid landscape peppered with shocking yellows and greens, but she stands in blue shadow. The goldfish bowl on the table distorts the view into a smear of color, and it seems as if the woman herself is trapped on display.

Finding Footholds in Garden Trellises

At the same time, the garden movement was feminine enough that some women found that they could use it as a platform to be activists, authors, and even critically-acclaimed painters themselves.

Celia Thaxter, depicted in Childe Hassam’s In the Garden (Celia Thaxter in her Garden), wrote an influential book in 1894 (An Island Garden) and was a fierce environmentalist, protesting the mass killing of birds to make use of their feathers as decorations for ladies’ hats. In her garden, she was able to be knowledgeable and significant, despite being only a woman.

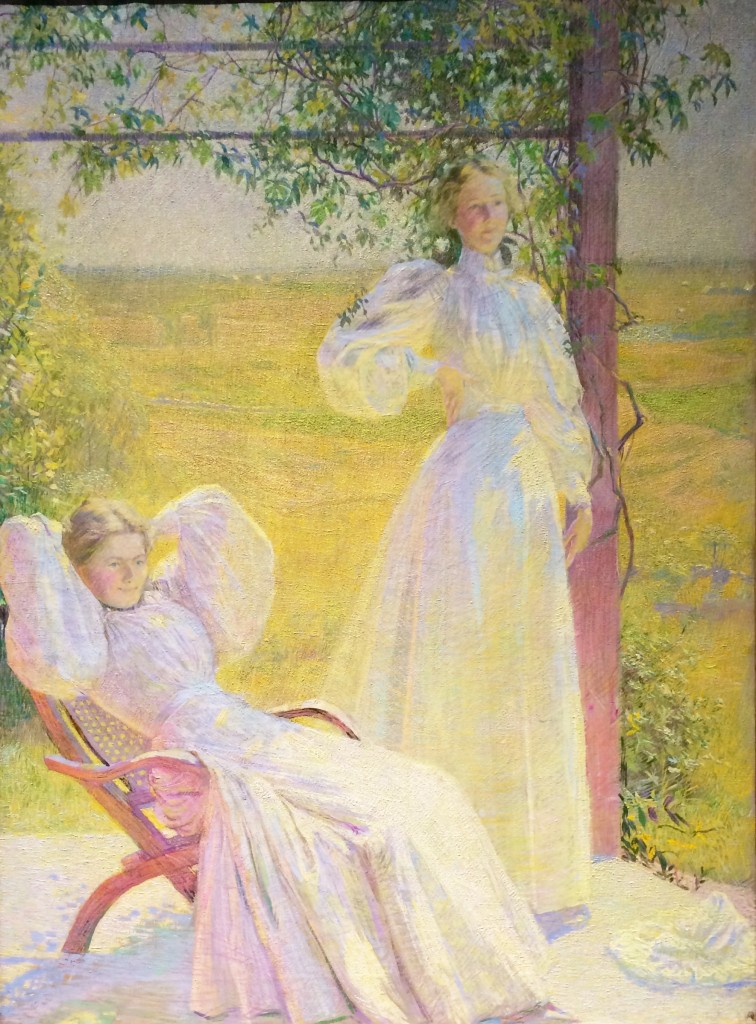

The walls of flowers could also serve as a welcome sanctuary for women to be untethered by the expectant gaze of society. In Top of the Morning (Philip Leslie Hale), two women are relaxing on a porch in poses that appear particularly masculine: one stands slouched against a post, while the other reclines sanguinely in a chair, her hands behind her head and a self-possessed smirk on her face.

Frederick Carl Frieseke painted his wife Sadie in the garden in Hollyhocks, and he gave her an agency not often seen. She is shown pensively handling the flowers, absorbed in their care, a serious horticulturist.

William Merritt Chase and Charles Courtney Curran also depicted women in a unique and authentic fashion for the time. Their paintings, Wash Day—A Backyard Reminiscence of Brooklyn and A Breezy Day, consecutively show women hanging laundry or laying sheets out on green fields to dry, their backs realistically bowed with their work.

When Women Bloom

Considering this progression of women rising in autonomy within the art itself, it was natural that feminine names began popping up on the placards next to dazzling paintings.

Maria Oakey Dewing’s large, intimate paintings of flowers were critically-acclaimed for her close attention to detail. Each soft petal and blade of grass is meticulously rendered, the uniqueness of every flower celebrated. She was praised for both her exceptionality in design and her ability to capture the essence of her floral subjects. In one of her most famous paintings, Rose Garden, the violet shadows of morning-glories speckled among the roses hearkens to the innate, crowded abundance of nature.

Tea Time Abroad, by Annie Traquair Lang, is a prominent example of the impressionist style; she painted with thick, textured brushstrokes and experimented with dappled sunlight, and there is movement in the way the woman subject sits forward, her hand delicately poised on a shining silver teakettle.

Jessie Wilcox Smith and Bessie Vonnoh proved that not all artists had to be painters. Smith found a career in illustrating for magazines, and Vonnoh forged garden sculptures from bronze. Both liked to focus on children, whether through Smith’s depiction of the garden as a space for domestic tranquility between mother and child, or through Vonnoh’s cheerful statues of small girls in their natural element.

Spring is already in full swing, and soon the paintings of the Garden Movement won’t be as desperately needed to ease our frigid souls. But even when the flowers lay down their heads to sleep until the next thaw, the rich colors and brimming life in each canvas will endure as a bookmark to an exciting time in America’s history, when women were just beginning to bloom.

The Artist’s Garden can be seen at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts [118 N. Broad Street] February 13-May 24, 2015; pafa.org.