The temperature in Philadelphia had been hovering around 32°F all day, leaving the roads coated in a slick icy film. It felt as though it were simultaneously melting and freezing beneath my tires. Trying to see past my wipers as they flung slush from my windshield, I wondered if anyone else would be foolhardy enough to drive through this weather to see Henrik Eger’s docudrama METRONOME TICKING at the Bryn Mawr Presbyterian Church. As I walked into the chapel, clutching my scarf close to my neck, I was pleasantly surprised to find myself in the company of a rather large group of people. We moved into the pews as a violinist played the theme from Schindler’s List and took our seats in the gilded glow of the stage.

METRONOME TICKING combines extracts from the memoirs of Lily Spitz, a Jewish Holocaust survivor, with selections from the personal letters written by Ernst-Alfred (“Alf”) Eger, a young and ambitious Third Reich propaganda officer, to tell a story of love and empathy in the time of the Holocaust.

The play features Henrik Eger and Bob Spitz, the sons of Alf and Lily respectively, alternately reading excerpts from the documents their parents left to posterity. Like Frank Dunlop’s Address Unknown (2001), a play based on Katherine Kressman Taylor’s novel (1938) chronicling a gentile and a Jew through their letters just before World War II—and performed recently by Seth Reichgott and Earnie Philips at Walnut Theater’s Studio 5—METRONOME TICKING is more a curated dramatized reading than a “play” in the traditional sense.

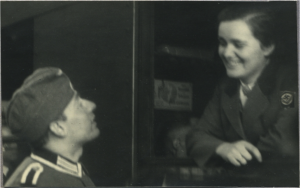

As the narrators read, images fill a huge TV screen behind them, and audio clips provide historical texture to the experience. At first, an invisible divide seems to partition the stage. Reading their lines in turn, Eger, wearing a Wehrmacht jacket, and Spitz, wearing a Star of David armband, sit at separate desks facing the audience rather than each other.

We are introduced to Alf as a young man, writing to his fiancée Gritt. Poised to begin his career as a journalist, he is ready to leave his impression upon the world: “Now the light falls onto my gold fountain pen, my gold fountain pen with which I will conquer my new profession,” he writes to Gritt, sure of his future. As Eger recites these lines with a befitting bravado, a handsome portrait of Alf fills the screen behind him.

The portrait introduces the audience to two Alfs: Alf the hopeful young man and Alf the hateful Nazi. We see him posing in his military uniform, his cap cocked to the side. His features are sharp, but his gentle expression betrays a cherubic warmth. Beneath this inviting visage, tucked into the corner of the photo, rests Alf’s swastika armband. Throughout the play, I struggled to reconcile this symbol of inhuman violence with the very human man that bore it.

Next, we hear from a young Lily living in Vienna, Austria, who is falling in love: “There was a charming, good looking man in his 30s who asked me often to dance with him, and we started to talk . . . I think I begin to fall in love with him. There was no doubt in my mind that he liked me also very much.” Spitz reads his mother’s lines in their German syntax and with an Austrian accent, filling them with a twinkling optimism. He sits beneath a faded, sepia-toned portrait of Fredl, Lily’s soon-to-be fiancé, as the first few bars of a Viennese waltz play from the speakers, inviting the audience to share their romantic moment.

Though two distinct characters, Alf and Lily’s narratives quickly entwine, crisscrossing over particular historical moments and mirroring each other’s themes, slowly eroding the barrier between their sons on stage. Love, marriage, forced separation, reunion, birth of a child, and loss of a loved one—we watch as Alf and Lily each experience these cornerstones of life. While World War II determines the chronology of the narrative, the drama of METRONOME TICKING emerges from their personal experiences.

The two live through the War in dramatically different positions. Alf, for example, reminisces over his time with Gritt in a National Socialist labor camp fondly: “We walked through the swampy woods, we sang.” Lily, however, agonizes over her fiancé’s treatment in a German concentration camp: “The men had to work in all kinds of weather without gloves . . . he was allowed to receive money to supplement his food or for buying hand cream, so we sent some. He used all of it to sooth his swollen hands.”

As Fredl toils away in Dachau and then in Buchenwald, Alf leaves Gritt to fight, first in Belgium, then in France, where he is promoted to take charge of the French press in Normandy. Lily, meanwhile, works frantically to acquire the papers necessary to get Fredl out of the concentration camp. Upon his release, they decide to flee from Austria to Italy.

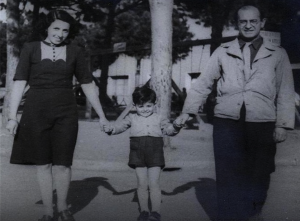

The war wears on everyone. Alf’s “sensibilities” begin to fade and his head throbs “like a hand grenade.” Lily feels drained of hope. Then, Henrik and Robert, the men we see on stage, are born into the story—nine days apart. In moments like these, Lily and Alf seem to experience the ups and downs of life quite similarly. Each rejoices in the prospect of becoming a parent; each struggles through the strains of childrearing and maintaining a marriage. Both pray for peace to return to the world. It seems that Lily and Alf share these experiences simply by virtue of both being human.

However, their brief moments of joy are quickly followed by more hatred and despair. Alf becomes firmer in his prejudices, recounting in his letters his commitment to wiping the “red vermin” (Communists) and “gold kings” (his code phrase for Jews) from Europe. Lily, realizing her mother has been taken to a concentration camp, sinks deeper into depression. “When I read the card I started to shake. I had no control of my arms and legs and I could not speak coherently. Robbyle in Fredl’s arms started to cry and poor Fredl was desperate.”

Just as Lily seems to have reached her darkest moment and Alf his highest, the play takes a turn. In the dimmed light of the interval between Act 2 and Act 3, Eger and Spitz exchange roles, trading their desks and outfits.

Lily’s story begins to focus on the compassion she receives from Italians, Germans, and others while hiding with her husband and son Robby from the Nazis. An Italian Priest pretends to solicit German lessons from Fredl so that he may pay the Spitz family some charity. A German ignores clear evidence that Lily is Jewish and chooses to give her food and cookies for her child rather than report her to the Nazi authorities. Acts of mercy and tenderness, though often punctuated with tense, uncertain moments, fill Lily’s portion of Act 3.

Lily and Fredl are liberated with the arrival of the Allies in Italy, but must struggle through the destitution of Cinecittà, a refugee camp outside of Rome, before, years later, they can receive American immigration papers and start their lives anew. During that time, Lily gives birth to her second child, who dies in her arms of diphtheria.

Alf’s ideological commitment is itself a third character in METRONOME TICKING, and swings through Act 3 in a sweeping arch into a tragic denouement. Early in the play, Alf is convinced of the Nazi ideology and its accompanying prejudices. “Hucksters, hucksters. Jewish Hucksters! Yecch. Jewish!” Alf howls in disgust, “Leave it to those Jewish merchants to get confused and get lost in the holes they created while knitting their own stockings. We’ll sew up their Lord and laugh through this hole.” Though Alf does confess his “pity” for the Jews, “these typical victims who had believed that gold rules the world,” it is clear that he remains convinced of the Nazi ideology that justifies their imprisonment.

As the war wages on, though, Alf begins to lose faith in its premise. “I look at the tanks in the streets below twice,” Alf confesses to Gritt, “once as a soldier who wants to destroy the enemy, the second time as a human being who accuses the warmongers.” He turns his criticism towards the whole project of modernity, lamenting, “the German caterpillar tanks destroyed seed and limbs. Oh ye miracle of technology, oh you outsmarted humanity, your pride, your work, your motorized destruction—how far have you progressed? Why doesn’t the caterpillar monstrosity pull a plow in order to feed all of you?”

Despite his grievances, Alf continues to support the war effort until he witnesses his own people commit a mass execution. We learn from the voice of a narrator that this experience shatters Alf’s worldview and leaves him shrinking into himself, “disturbed, afflicted, and lifeless,” until he disappears entirely, “missing in action” on the Russian front.

Lily’s guilt about not having saved her mother serves as METRONOME TICKING’S fourth character. It begins when she realizes she cannot afford a third ticket to Italy. With a heavy heart, Lily promises her mother that she and Fredl will return. After the young couple arrives in Milan, Italy, they learn that the War has broken out, the borders have been sealed to Jews, and “all of us foreigners” would be interned. “We must have come on the last train,” Lily realizes. Even decades later, she admits, “The guilt feeling that arose in me for betraying my mother has never left me.” Throughout her life, Lily would wear this guilt as a shroud.

METRONOME TICKING opens with both actors reciting an invocation, originally written by Alf, but equally fitting to Lily: “Read more than my letters. Read that which I did not write. Read that which could shatter my heart.” This docudrama puts it to the audience to do just that. To read Alf not simply as a Nazi, but as a loving husband, a proud father, a starry-eyed young man caught up in his own lust for success, who eventually realized what his hatred had done to others. To read Lily not simply as a victim but as a woman who fought the Gestapo and an oppressive concentration camp regime, and who found and gave love, even in the darkest moments of her life.

To let go of the caricatures we might have expected with a Holocaust drama; to read the humanity into each character we encounter with a generosity and empathy that could shatter my heart: these, I found, to be the most moving challenges of METRONOME TICKING. In an age when pundits toss around words like “Nazi” and “Holocaust” to end conversations before they even begin, METRONOME TICKING is a refreshing respite. [Bryn Mawr Presbyterian Church, 625 Montgomery Avenue, Bryn Mawr, PA] March 1, 2015; dramaaroundtheglobe.com/metronome-ticking.html

I saw this production and was deeply moved by this honest and balanced view of a very dark time in history. I especially appreciate that though Henrik was but an innocent little boy during this time, he has made his life about not only righting the wrongs of the Holocaust , but has become a crusader in favor of all that is good in the world, and against all that is not, quite simply stated.

Bravo to both gentlemen for this vulnerable and important work!

Denise, I only now saw your moving comment that you wrote over three years ago. I do not know how to thank you for your support for our work.

If only I could do more.

If I could perform in synagogues and churches and colleges and theaters in the US and abroad–not only bringing back the lives of our parents, but actually changing roles where I become the son of a Holocaust survivor and Bob Spitz the son of a bright and talented young German journalist who hated “Jews, Negroes, and Catholics,” I would gladly go on the road all year round,

hoping that some people in the audience would realize that it’s a pure coincidence of nature that we were born into specific societies and their belief systems and that, in spite of all the various cultural restrictions, we could still move forward as human beings respecting others, recognizing that

WE HAVE MUCH MORE IN COMMON WITH EACH OTHER THAN ANYTHING THAT MIGHT SEPARATE US.

Forgive the many words. They are my attempt to hide my tears.

Love, Henrik