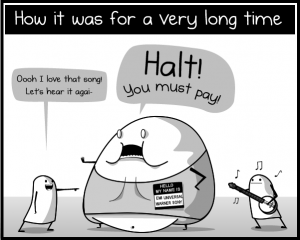

In the not distant past, I was watching a dance performance, which I was enjoying, and I couldn’t help thinking—if this dance company was caught by the people who own the publishing rights to those songs, they would never be able to do this performance again. Illegal use of music in professional dance companies is so ubiquitous you will see in anywhere from a warehouse performance to the Joyce Theatre in New York. You may notice the music being duly credited in the program, but you will rarely see the publishing permissions note that should also be there. If the music publishing industry has been cracking down on bar owners who play their own CDs (which is ridiculous), you can be sure that the end of dance performances using music without permissions is coming soon.

Not all dance companies are oblivious to the fact that they have been illegally using other people’s music for their entire careers, and while not completely abandoning the unlicensed use of music, they have been making greater efforts at creating works with original music through collaborations*, and even seeking out artists for permission (usually not the super-famous ones however) and often securing modest fees. Of course it is not just dance that is stealing music—theatre is also guilty, whether it’s pre-show music, or music played within a show or between acts. I even saw someone whine on the Theatre Alliance listserv in response to some crackdown—”you mean we’d have to pay for using a song in our show?? How do they expect us to do that?”

Not all dance companies are oblivious to the fact that they have been illegally using other people’s music for their entire careers, and while not completely abandoning the unlicensed use of music, they have been making greater efforts at creating works with original music through collaborations*, and even seeking out artists for permission (usually not the super-famous ones however) and often securing modest fees. Of course it is not just dance that is stealing music—theatre is also guilty, whether it’s pre-show music, or music played within a show or between acts. I even saw someone whine on the Theatre Alliance listserv in response to some crackdown—”you mean we’d have to pay for using a song in our show?? How do they expect us to do that?”

But 99 percent of the time, while most music in theatre is replaceable, in dance the music is inextricable. Just to be clear—any music that you play at a performance you need to have obtained the rights to do so, whether it’s a Smiths song you’re piping in (or playing live), or even the recording of a classical piece (you need to pay for the rights to use that recording, if not the music itself). Even in dance performances that have the audience bring its own soundtrack, say their own iPods, would be subject to licensing fees for whatever songs the audience played.

It is ironic that choreographers are so willing to basically steal music while they themselves are so protective of who gets to do their choreography. But putting aside that some choreographers are annoying self-absorbed narcissists, a dance that uses, say, “I Can’t Stand The Rain” is still its own creation even though it may well be completely dependent on that song. In that recent show I saw, which used A LOT of hits, I appreciated the soundtrack, which was essential, but the dance—meaning the choreography and the sound—became something quite different than just movement to a song and transcended into its own, original work of art.

An arguable parallel might be how rap artists and the Germans first appropriated samples to create new music. Music makers have been using pre-recorded slices from other artists to mold it into something unique for the past 35 years or so. In other words, the sample just becomes its own instrument. For dance, though it is hard to say with a straight face to the actual songwriter that his/her music is “found material,” in many ways, artistically, it is just that.

However you frame the argument, perhaps it’s like a color palette to a painter, it is important to stress the artistic merits of the choreographic process in relation to a piece of music and to clearly articulate your arguments in layman’s terms. Sooner or later the discussion with the offended is going to happen.

Some musicians may be surprisingly amenable to having their music in your show (they will need to have the publishing rights, however). So reaching out is not only the right thing to do, but may also yield pleasing results. Free is great of course, but the cost may not be as much as you feared.

I’ve no doubt this issue is on the minds of those within the dance community, but it is time to push the discussion into the open. As of now, the cost of music in dance seems to be very much on a case-by-case basis, and standards may be ad-hoc depending on who owns the rights. Ultimately, a dance advocacy organization, like Dance/USA, needs to actively work towards creating a low-cost, easy to facilitate manner in which dance companies can use music in their shows. While a potentially thorny definition of what defines a dance performance (or even a dance company) may create problems, a respected body like Dance/USA would be an important lead advocate because it is primarily speaking for dance as a performing art (rather then a cheerleading squad).**

Recently I saw that CD BABY created a service that makes it simple for bands to obtain the rights to record a cover song. The actual rights/fees were already established, but what makes this unique is facilitating the procedure by way of a simple online registration form. But there is a similarity in that independent bands have been putting out covers without paying the proper licensing fees for a long time, and not so much because they are loathe to pay the fees, but that the paperwork is burdensome (at least in band’s estimation of what burdensome is).

Ultimately a similar function would be of great benefit to dance, but the parameters will need to be set beforehand—a clearly defined and realistically affordable fee scale for dance works. If dance advocacy groups are the ones to bring the issue to the table—as opposed to having it forced upon them—then they are in a much stronger position to garner a sympathetic understanding of the economic scale of dance companies, as well as the artistic rewards to one’s music being involved in dance.*** If the dance community begins the dialogue in earnest with musicians and publishing houses, it means they can help frame the conversation.

If affordable guidelines can be negotiated with major publishing houses like ASCAP, then those same guidelines may set an industry standard that can also be negotiated with other music publishing holders. It may take a while to get every single song or piece of music on there, but if you had a deal with the 4 or 5 top music publishing holders you would have an enormous catalogue to choose form. Creating a simple online registration for licensing fees with music might also allow companies to secure the rights, while including the actual fees with the presenting costs.

It’s a subject that dance companies and choreographers are naturally uncomfortable with speaking about publically, because expressing concern with the issue almost immediately brands you as a transgressor. But choreographers should have the freedom to create work from whatever source inspires them. Perhaps not for free but certainly for an affordable fee.

Published by the Philadelphia Performing Arts Authority

*Collaborating, however, may not be what just anyone can afford to do, want to do, or even know those whose music they’d want to do, i.e., a harder proposition if you are not established.

**I’m picking Dance/USA because they’re the one I’m most aware of, not because I am picking on them.

***Good will is important in negotiations. So here pragmatism and doing the right thing meet!