Republished from kind permission from Roz DeKett’s The Right Word

“I have hated this play sometimes,” says Doug Williams. Strong words, when you’re talking about something you’ve written yourself. But it’s not so much the play: it’s the formidable struggle with writing and rewriting that drives a playwright to the brink.

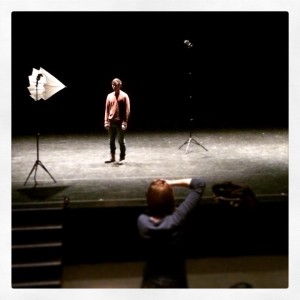

Now, though, it’s all paying off for Doug. After a year of development (a euphemistic word that glosses over the scene-shredding and embattled hours of redrafting that’s an integral part of any play that makes it to the stage), Moon Cave, Doug’s first professional production, has its world premiere with Philadelphia’s Azuka Theatre in March.

Doug is this season’s playwright-in-residence at Azuka, which means frequent meetings with the theater team and readings with actors to discuss and test his drafts as he writes. The play had its first public reading at the PlayPenn New Play Development Conference in 2014. He’s been working with Azuka’s director Kevin Glaccum from before that.

But while developing a play is collaborative, with a safety net of support for the playwright, it’s not for the faint-hearted.

“It can be nerve-racking,” Doug says. He laughs, somewhat ruefully. “I don’t know why I do it to myself. You work so hard to finish a draft. You try to figure all these things out and you know something’s wrong. It takes you a week, but you crack a scene. It feels so great when you finish a draft; now you can read it backwards and forwards and it’s a story.

“Then you hand it in [for review] or you have a reading and, almost immediately, it’s back to the drawing board.”

Hearing the text read by actors and getting feedback—notes—is crucial to a play’s development, and playwrights must endure their new work being challenged, inspected, held up to the light to look for the holes. Fixing problems can mean making changes that are substantial and structural: sometimes, Doug says, “You’re just really upset about where the play is.” As Moon Cave progressed, one scene—the core idea that sparked the play and the first scene that he wrote—was initially at the beginning, then got pushed to the end, and finally, vanished altogether.

“Leaving a reading I’m already exhausted, knowing the work that I have in front of me,” Doug says. “Every time you get notes you’re trudging back. I have to sit down and say all right, this scene that I’d worked so hard on isn’t even going to be in the play. And that’s difficult to do.”

But as they transitioned from readings to rehearsals, Doug felt the play strengthening.

“As we’ve been doing more readings, afterwards I’m feeling less and less depressed or daunted,” he says. “There are fewer and fewer notes, and now they’re less about things that might change and more about the designers and the actors discussing the text and what’s going on in the play.

“For me, it’s very encouraging.”

So how did Doug get here, to a point where he’s spent a year wrestling his way through the creation of a play?

It all started with the movies.

From film to something “strange and different”

“Around the age of 13, I started making films,” Doug says. “I would make films with my sister and my dog. I could put them on the internet, people could see them, and I enjoyed editing a lot too.

“So I was writing, but really it was a means to be able to make a movie.”

Doug’s interest in film took him from his home, a small town in Connecticut, to studying it at Temple University in Philadelphia. While there, he took a literature class on American playwrights with Ed Sobel, formerly head of new play development with the Steppenwolf Theatre Company in Chicago.

It transformed Doug’s thinking about theater.

“We were reading a lot of contemporary stuff and it sort of blew my mind,” he says. “I had pictured theater as Our Town and Damn Yankees, or whatever musical my high school was doing. So that was really fascinating, that this type of contemporary work was being written, that there were theaters producing this kind of material.”

Along with his new understanding of contemporary theater’s edginess and its willingness to step out over the abyss, Doug began to find frustrations with film as a medium.

“It’s become so much more cookie-cutter,” he says. “It’s because it’s mass media. Film is just such a different art form.

“You have a small theater like Azuka, and they can invest in a play, and be strange and different, and they’re interested in taking risks. And that’s really exciting.”

It was too late for Doug to switch his major from film or do any kind of minor in theater. But he was hooked. After graduating with a degree in film, he got an internship at the Eugene O’Neill Theatre Center in Connecticut. From there, he became an intern in the literary department at Manhattan Theatre Club in New York.

“I still really use the knowledge of what happens to a play after it’s written,” he says. “How a theater sees it, what they’re interested in, what the programming conversations are like, how a play gets produced, how they decide to produce a play. Every day we were dealing with that, and obviously, the Manhattan Theatre Club is another scale. They have half a million subscribers, and they’re producing new plays in Manhattan, so it’s certainly different than Philadelphia.”

And as a theater intern in New York, Doug had the benefit of free tickets. In his two years there, he saw an average of two plays a week. But nonetheless, money was tight and after his internship ended, working two jobs left him little time to write.

“It’s very hard to get any kind of footing in New York in terms of a career and also in terms of being a writer,” he says. “I just could not afford New York. It’s really impossible, especially for artists. I think if I’d stayed there, I probably wouldn’t be writing plays anymore.”

So he moved back to Philadelphia.

New York’s loss, Philadelphia’s gain

Whereas the response in New York, a city awash with playwrights, was often indifference if he mentioned he was writing a play, Doug quickly found a very different culture in Philadelphia’s thriving and supportive theater community.

“I was meeting other people who work in the theaters, and meeting people like Kevin, who runs a theater,” he says. “He makes himself accessible and he’s like, send me your stuff. And he’s not the only artistic director in town that’s like that.

“It’s just so great that it’s so much more friendly, as opposed to New York. It’s a smaller community and plays are being produced on a different scale, but in terms of where I was as a writer, I was really able to hit the ground running. So many people were very interested in my work, which made me want to write more.”

Doug has other plays at different stages, in particular one centered on a bike shop—he worked in one in New York. With Moon Cave completed, he’s now looking at these plays with a different eye.

“As any writer would hope, I’m sure, as they go along, you can get better, you hope you get better,” he says. “So I think I’m better than when I started that bike shop play. I don’t want to start over but I’ve been trying to play with it in that way, use the things that I’ve learned from writing Moon Cave and from working with this team, to make it more of a play.

“Right now it’s very traditional, and I’m trying to make it a little more contemporary and like the plays that I like to see. And a little more like Moon Cave.”

As Doug approaches Opening Night with Moon Cave, he reflects on working with Azuka.

“Kevin read a very early draft, and looking back, he had a lot of faith in me, in just a messy first draft,” he says.

“Theater is of course a collaborative art form. So to have a dialogue with the people you’re working with is important to me, and I would hope it’s important to the people who are giving the notes, who want to be heard.

“I think that kind of care, honoring the text, and the collective effort, and trying to make it the best thing possible: I have certainly felt it. I feel like I’ve had this great big team of people that are really excited about this play.

“I feel lucky to be part of it.”

© Roz DeKett

The world premiere of Moon Cave is at the Azuka Theatre in Philadelphia from March 4-22, directed by Kevin Glaccum and starring Taysha Canales and Kevin Meehan. You can get tickets here, learn more about Azuka Theatre here, and join their mailing list here.

Read more features and interviews with playwrights, authors, and poems at The Right Word.

About Moon Cave

Terrified that someone will recognize him from a childhood trauma that made national news, Richard keeps to himself. That all changes when he meets Rachel and starts letting down his guard. Richard must tell Rachel the secrets he’s been hiding, but will she still love him when she knows the truth? And if Rachel knows, how soon before the rest of the country will be knocking down his door? This World Premiere work is a nuanced look at notoriety, responsibility, and living with mistakes.

About Doug Williams

Douglas Williams is the Playwright-in-Residence at Azuka Theatre in Philadelphia, where his play Moon Cave will be produced during the 2014-2015 season. Moon Cave was developed at the 2014 PlayPenn New Play Conference. Other plays include The Death and Life of Uncle Gene, Now I Am A Wrecking Ball and Shitheads, which was a finalist for the Lark’s 2014 Playwrights’ Week and a semifinalist at the Eugene O’Neill Theatre Center’s National Playwrights Conference. Doug is a member of Orbiter 3, a playwrights producing collective, and is also a member of The Foundry, a lab for early-career playwrights led by Michael Hollinger, Jacqueline Goldfinger and Quinn D. Eli. He is a graduate of Temple University.

One Reply to “Finding art in taking risks: Doug Williams”