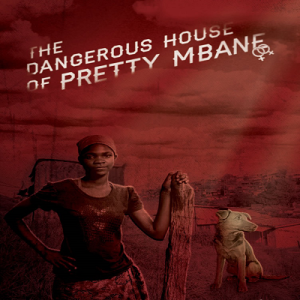

Jen Silverman, a young playwright with a long record of awards and plays that were performed all over the U.S. during the last few years, was born in the U.S., but has lived in Asia and Europe as well. A graduate from Brown University and the Iowa Playwright’s Workshop, she presents a wide range of characters, especially women. Her latest drama, The Dangerous House of Pretty Mbane, winner of the Kennedy Center’s Paula Vogel Playwriting Award, has been in development for the past three years. Its world premiere production by InterAct Theatre Company opens tomorrow, January 21, and runs through February 8, 2015. Henrik Eger talked to Jen about her background, the play, and the issues it raises

Henrik Eger: You once said, “I have a complicated relationship with my nationality—as, perhaps, do most American artists.” Tell us more about that ambiguity, especially at a time when millions of people seem to feel uncomfortable with artificial borders and nationalities and are beginning to search for new identities.

Jen Silverman: I’m American: I have the passport, I was born here, I went to high school and college here. And then also–I’ve spent real time in other countries, as both a child and an adult. A lot of cultural givens for American kids weren’t cultural givens for me. Going to high school in Connecticut was sort of a crash course. My assumptions and norms were so different that I felt like I’d arrived on another planet. As a high school kid, you’re just trying to survive what is essentially a Gulag of hormonal insecurity-driven conformity. After the fact, you get to ask: OK, what parts of my nationality and culture actually resonate with me, and what are the things I learned to “put on” so I could “pass”? It’s complicated.

It remains complicated as an adult and a working artist in that, on the one hand, America’s value and support of its artists is grudging, at best. It’s hard not to think about picking up and going somewhere else. On the other hand, if America’s artists and writers bail, if we abdicate responsibility, then what happens in our wake? I think we’re responsible. There are doctors of the body and doctors of the mind. A country can’t lose either and still function as a healthy organism.

Eger: You were home-schooled until high school, moving from one place to another. How did those experiences impact your ways of seeing life and writing plays?

Silverman: Being homeschooled is something that people find hard to wrap their brains around. They think I was either raised in the basement with a Bible, or that my parents set me loose to run with the wolves. It was actually a very consistent, if fluidly-structured. My parents are people who think and question and want to know things, and then question those things. They are both scientists with very critical, keen minds. Being homeschooled was about being raised to question everything, be wildly curious, be responsible for that curiosity.

As a kid in Paris, I studied some French grammar, but I also wandered around and talked to strangers and learned French that way. Homeschooling in its best form is about encouraging a child to pursue his or her curiosities with passion and attention to detail, which is also a big part of being a playwright, or any kind of generative artist. You fall into obsession, and then you pursue it like a bloodhound.

Eger: You’ve talked about “my communities.” Could you give a few examples of your identities within those communities—as a person and a playwright?

Silverman: I think fluidity is integral to my sense of identity, and my communities are often comprised of people who also live with and constantly navigate a kind of fluidity—whether it’s sexual, gender-based, national, linguistic.

Eger: Do you use different languages in your plays? If so, how do you keep your audience members on the same page? If you only use English throughout, what happens to the authenticity of the various places and people you want to portray?

Silverman: I used to experiment with that, and then I got really interested in playing with the stretch and expanse of English, what it can do, where it fails. English is my native language after all. I speak other languages to varying degrees, but I can’t pretend to be able to use them with the same ease. I think authenticity lies in depth, complexity, compassion.

If I create a character with enough depth and complexity that the audience feels compassion, that could perhaps be considered a success. This is not to say there isn’t real value in using multiple languages in a play and making an audience reckon with them–a number of the playwrights I respect do that well. It just hasn’t been my approach yet.

Eger: Going by the many plays you have written, workshopped, and rewritten, and considering the hundreds of entries on your blog it seems that there’s little time for any private life.

Silverman: I think there’s an important distinction to be made between the work and the person (who works), even in the arts, where it’s complicated by the fact that our work and our passion and our sense of self all get elided.

I’m fierce about my privacy. I’m fierce about keeping secrets–my own and other people’s. Plays are plays; you craft them and your collaborators help you grow them, and then they become these separate animals that stand up and speak for themselves. [My] blog is half-joke and half-experiment–I think real life is a stunningly absurd thing to experience, and the blog is a place to report back on all of that absurdity. But, there’s an inner life that we have to protect in order to be able to create, and also to be trustworthy friends and partners. That demands a certain rigorously defended boundary–what you’ll share and what you won’t.

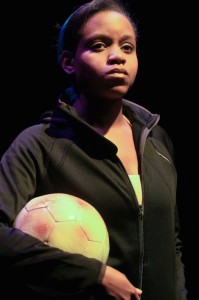

Eger: Where and how did you discover your empathy with South Africans? And how did Noxolo, the talented lesbian soccer player who flees her country to escape violent homophobia; her lover, Pretty Mbane, the political activist; and the other characters in this play come into being?

Silverman: There’s a small but thriving community of South African expats living in Japan. Very close friends in that community first introduced me to a lot of art, music, political satire, and then, of course, the actual political situations that lay under that satire.

Eger: South Africa was one of the world’s worst countries for apartheid, only to become a beacon of hope for equality—not only for ethnic groups, but for sexual minorities as well. At the same time, ongoing political unrest and crime rates show that the country is still struggling with a number of issues. Your play shows Noxolo’s search for her lover which reveals South Africa ignoring the violence against women. How did you come up with the controversial subjects in your play and what were the main hurdles in shaping The Dangerous House of Pretty Mbane?

Silverman: The play was inspired in large part by a petition created by Ndumie Funda of the Capetown organization, Luleki Sizwe. The petition demanded that the South African government acknowledge and deal with “corrective rape.” That was the first time I’d heard of “corrective rape” in those terms, and I started doing a lot of digging, talking to my South African friends, asking questions.

I’d been in Japan during the 2010 World Cup, which was held in South Africa–and (weirdly) coincided with the South African band Die Antwoord [Afrikaans for “the answer”] coming to Osaka. It seemed like every South African in the country came to Osaka for that concert. I was having all of these really intense and honest conversations with my friends and their friends and total strangers about what it was like for them to be in Japan and suddenly hear their country as a common topic of conversation, turn on the TV and see South Africa—what that felt like, what questions it raised about their choice to leave, etc. The convergence of these conversations with Ndumie’s petition was where this play started.

Eger: Thank you for addressing issues that few people dare to talk about. What’s next?

Silverman: I’m currently in two different rehearsal processes, going between Philly and New York this week, with the draft of a new play commission due shortly.

Eger: Many thanks, Jen, and baie dankie.

[Adrienne Theatre, 2030 Sansom Street] January 16-February 8, 2015; interacttheatre.org.