Excerpted from a full-length review on Neals Paper. Republished by kind permission.

An early scene or two obscures the potency of LITTLE ROCK, Rajendra Ramoon Maharaj’s poignant play about nine children who integrate Little Rock’s Central High School, but the thoughtful and moving piece gains dramatic traction and glides its way towards a lasting impression.

Maharaj approaches LITTLE ROCK as a documentary. Much of its dialogue comes directly from judicial transcripts and interviews the playwright conducted with the “Little Rock Nine,” as the students ranging in age from 14 to 17 in 1957, came to be known. Maharaj presents his material chronologically, starting in 1954 with the recently appointed Chief Justice, Earl Warren, reading his Court’s unanimous decision on Brown, and ending with the morning in June 1958 when, in spite of death threats and other warnings, Ernest Green walks up the steps of a Central High podium to accept his diploma as the first, and one of the few, of the Nine to be graduated from Central.

Maharaj approaches LITTLE ROCK as a documentary. Much of its dialogue comes directly from judicial transcripts and interviews the playwright conducted with the “Little Rock Nine,” as the students ranging in age from 14 to 17 in 1957, came to be known. Maharaj presents his material chronologically, starting in 1954 with the recently appointed Chief Justice, Earl Warren, reading his Court’s unanimous decision on Brown, and ending with the morning in June 1958 when, in spite of death threats and other warnings, Ernest Green walks up the steps of a Central High podium to accept his diploma as the first, and one of the few, of the Nine to be graduated from Central.

In general, this chronology serves well as an organizing framework, but at the top of the play strict attention to the order events occur bogs down the action and delays what journalists would refer to as the “lede.” Earl Warren’s speech is significant, but it has no power. Nor does a scene in which Elizabeth Eckford (Gia McGlone), the student chosen as the first in line to enter Central, gets ready for her initial day and spars with her parents over her agreement to be a civil rights pioneer. A fear, soon dispelled, emerges that Maharaj is going to be dry and pedantic.

The scene of Elizabeth’s first, aborted attempt to forge past jeering, expectorating pickets and get within doors blocked by Arkansas National Guardsmen deployed by Governor Orval Faubus is Maharaj’s true opening. It shows in a tight, meaty nutshell what happened in Little Rock when all a teenage girl wanted, in her own words, was “to go to school.”

Maharaj economically but palpably captures the meanness, anger, and sincerity of the bigots. Three actors, with signs, yell insults and slogans, sometimes making up rhymes and racist jokes thinking they are being witty. With this scene, LITTLE ROCK singes its way into your mind and stands as a testimony to one year of determined struggle that symbolizes centuries of wrongs being corrected by brave, positive action on the part of the suppressed who refuse to be relegated to second class citizenship.

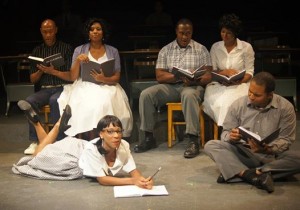

LITTLE ROCK is at its most pungent when the actors representing the Nine tell their overall histories in their own words. The sincerity of the nine stories, collected by Maharaj during almost a decade is the crux of the play. Maharaj is helped by a uniformly talented cast, each of whom is called upon to play a number of roles — parents, administrators, NAACP leaders, and historical figures such as Eleanor Roosevelt, Rosa Parks, Louis Armstrong, and Martin Luther King — and does so with aplomb.

Maharaj proves deft in finding ways to include the background information that gives the Little Rock Nine story texture: Gov. Faubus closed all Little Rock schools in 1958 as a tactic to stall any further integration; President Dwight D. Eisenhower federalizes Arkansas’ National Guard and sends the 101st Airborne to accompany Elizabeth Eckford and her classmates to the door of Central.

The effect is one of authenticity, and LITTLE ROCK has the documentary clout and engaging nature of an Anna Deveare Smith play or Moises Kaufman’s Laramie Project, both of which were models for the piece [Passage Theatre at the Mill Hill Playhouse, 205 E. Front Street, Trenton, NJ] October 2-26, 2014; passagetheatre.org.