Dear Phindie readers,

Because of inappropriate comments I made in my introduction to this interview with Mary Tuomanen, we have chosen to add a disclaimer to this interview.

By making my interview about Debra Miller’s opinions of the play, I invited readers to attack her and posed see her as an exemplar of censorship—which is not in the least bit properly representative of her review. By acting without considering my actions or my prejudices, I did damage.

Dr. Miller pointed this out to me, and I did not believe her. [Please read Dr. Miller’s comment on the piece, below: click here] It was only after multiple people had either approached me about this, or else made inappropriate comments on the article, that I realized the cruelty of my piece.

Particularly as an editor of Phindie, an independent criticism website intended to improve the theater community, this was not only unprofessional of me and unkind, but also damaging to Dr. Miller and to a worthwhile discussion.

This does not reflect Phindie’s perspective on the issue nor Ms. Tuomanen’s. The concepts which Ms. Tuomanen discussed are still pertinent, but because of my inappropriate framing of them, we have decided that we must add a disclaimer to the article. We are not interested in removing the interview from the website, but we cannot host it without admitting my error.

Yours apologetically,

Julius Ferraro, Phindie theater editor

—

Phindie writer Deb Miller got the first word on The Body Lautrec, Aaron Cromie and Mary Tuomanen’s dance/drama about the life and livelihood of French post-impressionist painter/bohemian Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Lautrec, famous for his unusual body and his paintings of prostitutes and their unglamorous lives, died of syphilis in his thirties.

The play uses clowning, burlesque, some surprising realism, as well as nudity and crudity to investigate the themes of Lautrec’s work and the somewhat depraved life he and his friends lived. Miller’s review suggests that the “crudity” in the piece “repels,” existing in order to create “a convincingly debased tone.”

Having seen the piece myself (admittedly on a different night) I felt that Miller’s perspective, though exquisitely worded and careful not to disparage the work of the performers, skewed the piece’s intention. By putting filth first, she misses out on what seems to me an intricately rendered and in fact smartly feminist play.

Her review opens the door on an important conversation about nudity on stage, a conversation Philly’s feminist theater-makers have been struggling to create.

I asked Tuomanen, who directed the piece, to talk about The Body Lautrec. On extremely short notice, she agreed (“Aaron called me, said someone was upset about Lautrec and you wanted to ask me some questions.”) We talk about filth, exploitation, agency, and other uplifting stuff.

Julius Ferraro: So Deb’s review came out, and she was kind of disgusted, and you find that fascinating.

Mary Tuomanen: Yeah, definitely.

JF: Why?

MT: It’s interesting that we’re making a show about a painter who, when he exhibited his paintings in Paris, he had to have them covered with velvet cloth, like certain paintings in the brothel series, they weren’t just displayed, you’d have to go into a different area and lift up a cloth to see his paintings.

They were found very offensive at the time, so I think maybe . . . I’m surprised we’re offending someone because I certainly don’t think the show’s offensive. But if we are, maybe we’re doing something right.

JF: I saw the show last night, really enjoyed it. But Deb’s review displayed disgust with everything from the explicit nudity to the conversation about nipples.

MT: I’m surprised that a woman can’t talk about her nipples on stage without offending somebody. Especially when she’s playing a prostitute.

JF: The piece is pretty explicit, it’s more explicit than most people are used to.

MT: You’d think in this town . . . Charlotte Ford did Bang, and people, especially women, are constantly trying to re-appropriate nudity on stage. It seems to be a major struggle, and certainly we did a lot of negotiation with it in our rehearsals. We did a lot of naked rehearsals where everyone, the stage manager, everybody, I was, everyone was nude. And we would just do a bunch of crazy stuff, at one point we used paint to see if that was interesting. We smeared paint all over each other.

We really wanted a moment in the show when everybody was nude. And certainly I hope the show does have a continued life and if it does have a continued life it’s something I want to figure out a way to do.

And because of the organic way in which we explored the nudity, and the . . . line in the scene where Kate [Raines] talks about her nipples, the lines in the scene were improvised by the actors. Most of the text comes out of either improvisations that the actors did or writing they did about their characters individually.

Like, I curated it and edited it and stuck it together, but it’s . . . I’m surprised. It’s interesting though. It’s also good to strike a chord with people. I do think we are a little backwards in America. Everyone has the right to be offended. But I do think that we’re much more cagey with nudity than other countries. One of the actresses in the show is Polish and she was a classmate of mine at the Lecoq school. And when I approached her about the play I said there might be nudity and she was like, yeah, uh huh, yes? She was nonplussed by the idea. And it’s still a little scandalous in America in a way that it’s really not in Europe.

I don’t know if you’ve seen the Castellucci. It was really gorgeous but there was also a lot of nudity in it. And . . . it’s part of the gorgeousness of the piece, but certainly I’d heard about the piece earlier from people who had seen it in Avignon, and they were American, and they all mentioned the nudity. Even though it’s not a major part of the piece. But everybody mentioned it. And people think it’s still wild in Philadelphia. Or because it’s a button, people think it must be pushing buttons.

How do we women speak to other women on stage, how do we have fun with our bodies and be silly about our bodies and speak to other women and not feel the male gaze in the way all the time? It’s a major question.

JF: Tell me about Lautrec.

MT: Lautrec was such a different painter than Degas and a lot of his contemporaries. Because when you look at a person he’s painting you recognize her as a person. You recognize the character. You’re like, oh, it’s that lady Carmen. He painted her again. You know what I mean? And he often paints them in their context and you see their lives. And he lived in a brothel with these people, these were his friends. And some of his friends died, and he died early as well. People were selling their bodies and people were dying of terrible diseases.

This was his reality and it’s certainly what we’ve tried to bring to bear on the piece. And that’s certainly why it’s as gory as it is and as nasty and medical as it is. I don’t meant to imply that all medicine is nasty, but I just mean to say that the particulars of a dying body are not pretty.

I think she totally has the right to be offended. I’m sad if she felt that male gaze between her and the women on stage. Because I had the outside eye on that and I’m a woman. And so I’m the intermediary between that stage picture and her, the viewer, so she in some way either mistakes me, or it’s just hard to let go of the vice grip of the male gaze on all our brains. I don’t know why, but I’m curious about it.

JF: I think one of the problems is people are sensitive to nudity on stage. People get the idea of trying to reclaim nudity on stage but I don’t think they understand how that can be done, how you can show naked women, and show naked sexualized women, and have that not be exploitative.

MT: Yeah, it’s funny, when you talk about the word exploitative we’re talking about teleological nudity, right? Nudity for the sake of something. Art is intrinsically non-exploitative. It doesn’t fit into a capitalist model. We get in trouble all the time because we’re trying to do a thing that doesn’t work in a capitalist economy. And the word exploitative carries capitalism with it. And yes, sexuality, particularly female sexuality is used to sell everything. You can sell a chair with a scantily-clad woman. You can sell any damn thing with a naked lady, or with a scantily-clad lady, or a woman implying in any way that she might be sexually available.

But art intrinsically . . . you buy a ticket and you’re on a ride and it can’t sell you anything else. The transaction’s over. The transaction part is over, and now you’re on the ride. It can’t sell you anything else. It’s not teleological. That’s the end. It’s an end in and of itself.

What I’m saying is . . . it’s sad that it’s hard to make people feel that a woman getting sexual on stage and nude—although incidentally in the nude scenes in Lautrec people aren’t being particularly sexual. They’re usually talking about their diseases. Their rashes and bleeding and pussing and having catheters put up them. So it’s not really sexual. Unless you’re into that. So that a woman being sexual on stage and nude necessarily carries money with it, carries the idea of money with it, that’s so sad.

JF: I think when people see nudity they ask why it’s done. It’s like anything else that’s not done often, then we ask why. It’s not like when someone bounces a ball on stage, because that’s just their character. If someone walks naked onto the stage we want to know why they’re naked. And one easy answer is that it’s edgy and it sells tickets. So why show nudity on stage, particularly female nudity, and why in this particular context?

MT: Certainly if you look at the body of work of this particular man there’s a lot of nude women. In order to accurately represent the painter we should talk about what he painted. And he did paint a lot of nudes. A lot of half-dressed women, women getting dressed and undressed, and usually in the context of a particular trade which has to do with selling one’s body. And he also painted them—the most fascinating Lautrec painting I found in this process is the one called Medical Examination. Which is, at the time, Paris was trying to control syphilis by actually sending public health workers to the brothels to check on women and to take them out of the rotation if they were found to have syphilis in them. If it was a high class brothel it would get individual visits with the doctor and it was a private sort of thing. If it was a less expensive brothel, the women would line up like cattle and hold up their dresses and the doctor would check the women. Lautrec painted the women marching in line—it’s in D.C., it’s in the National Gallery—marching with their little shifts above their crotches.

Lautrec paints non-sexual female nudity, and like, brutal non-sexual female nudity.

There’s a whole series, called Elles, which is the female version of “they,” which was supposed to be this big scandalous thing. He was going to paint women in a brothel. And people were really excited about it, it was going to be super salacious.

And the women are looking exhausted, tired, disappointed with their lives. They are very striking, depressing, drawings. And there’s one called Alone, where a woman is just done with her life. She is laying back on the bed and she’s so tired. And we quote it several times in the show as well, that particular painting.

Why Lautrec is fascinating is because he was painting the female nude and showing women, who were usually friends of his because he lived in the brothel, in positions of despair, in positions of exhaustion, women whose jobs it was to provide sex feeling entirely unsexy in really unsexy times. In times where they were sad, alone, exhausted. And they’re beautiful! But they’re super depressing.

So in the case of this particular play we would be remiss were we not to try to capture all of that.

JF: How about male nudity?

MT: We definitely, in there are future versions of this show, we would love to maybe add more nudity and hopefully have male nudity as well, if we can find room for it. Because like, I can understand people thinking, I wish there was more parity. Because obviously there’s baggage. There’s terrible baggage with female nudity more so than there is baggage with male nudity. And there’s much less a history with the male nude in painting than there is a female nude. And so of course you’re allowing for some parity. Probably there should be more ass. There should probably be some more of the naked man-butt. A little more of that the next time we do the show. I’ll ask Aaron to throw in a little more.

JF: I don’t think Toulouse-Lautrec ever painted himself naked?

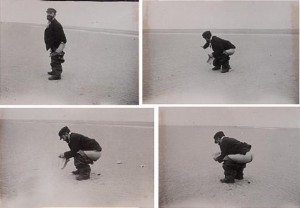

MT: He definitely took pictures of himself naked. There’s a very famous photograph of him defecating on a beach. He’s like, “Check this out, guys!”

There are several photographs showing the whole process of his defecation. It’s really scatological. He was nuts. There’s actually a photo of him entirely nude standing up in a boat. So he definitely loved being naked.

JF: The women portrayed in Lautrec’s paintings are doubly removed from control. they have no agency in their lives and then they don’t really get to choose how Lautrec portrays them. When women are nude on stage, which is traditionally a patriarchal trope, we want to see that those women have agency. How do you use agency in the play?

MT: The female characters in this play have little to no agency over their bodies. Gosia, the Polish actress in our show, makes a good point: “To speak about Belle Epoch women as having agency is complete anachronism.” She’s right, even a middle-class woman in this place and time had little to no choice about the fate of her body, particularly in the context of a marriage. And the women we are showing are 19th century sex workers—their choices are practically nil. We show women struggling through their infirmity to complete sex acts, we show women jumping around to create a “party atmosphere” in a brothel and as soon as the male characters leave, they collapse with exhaustion. At the same time, we make an effort not to moralize. There was a concern amongst the cast that was brought up during rehearsal—”Are we saying that sex work is wrong?” And certainly, that is not our intent in creating the piece. The fact remains, however, that there is a major difference between sex work today and the profession as it existed in 19th century France—this is a country where a woman could not have a bank account of her own without a male cosigner until 1968. So you can imagine how it was in 1901!

This loss of agency is something the Lautrec character can understand because of his complex medical history. He had a congenital bone disorder that left him bedridden most of his childhood and handicapped as an adult. His body has also been an object; the whole show centers around the idea of human body as medical object, sex object, art object. We show Lautrec as a child trying to fight off the doctors who are about to break and reset his legs, they cover his face with a cloth smothered in ether. We see prostitutes made to hold up their dresses to the audience as examples in a medical lecture—they’ve become objects. (This is an image that Lautrec captured in his painting Medical Examination, something only Lautrec would paint because among his contemporaries, only he was interested in showing these brutal aspects of prostitution.) Later, a grown Lautrec watches his friend in the paranoid throes of tertiary syphilis begging not to be left alone with the nurses, screaming that she needs to protect herself, moments later she is autopsied. Disease itself robs a body of power—it can rob us of mobility, of cogency, of memory, of dignity, of the will to live. One of the most powerful moments of the play, for me, is when Lautrec and the character played by Kate Raines—amongst the cast we call this character Jane, inspired by Jane Avril—sit on a bench, look at each other and say simultaneously, “It hurts. It hurts. It hurts.” They say it in French, which always felt right, because of the vowel sounds in “ça fait mal,” which are so mournful and sad. This is an actor-guided moment. We never set how many times they say “It hurts” to each other. They just say it for as long as it takes. And this is the part that hurts me, too. This is what it feels like when your body gets taken from you. It hurts.

This loss of agency is something the Lautrec character can understand because of his complex medical history. He had a congenital bone disorder that left him bedridden most of his childhood and handicapped as an adult. His body has also been an object; the whole show centers around the idea of human body as medical object, sex object, art object. We show Lautrec as a child trying to fight off the doctors who are about to break and reset his legs, they cover his face with a cloth smothered in ether. We see prostitutes made to hold up their dresses to the audience as examples in a medical lecture—they’ve become objects. (This is an image that Lautrec captured in his painting Medical Examination, something only Lautrec would paint because among his contemporaries, only he was interested in showing these brutal aspects of prostitution.) Later, a grown Lautrec watches his friend in the paranoid throes of tertiary syphilis begging not to be left alone with the nurses, screaming that she needs to protect herself, moments later she is autopsied. Disease itself robs a body of power—it can rob us of mobility, of cogency, of memory, of dignity, of the will to live. One of the most powerful moments of the play, for me, is when Lautrec and the character played by Kate Raines—amongst the cast we call this character Jane, inspired by Jane Avril—sit on a bench, look at each other and say simultaneously, “It hurts. It hurts. It hurts.” They say it in French, which always felt right, because of the vowel sounds in “ça fait mal,” which are so mournful and sad. This is an actor-guided moment. We never set how many times they say “It hurts” to each other. They just say it for as long as it takes. And this is the part that hurts me, too. This is what it feels like when your body gets taken from you. It hurts.

Thanks, Mary! You can see The Body Lautrec at the Caplan Studio Theatre, University of the Arts, 211 S. Broad St., 16th floor. September 12-21, 2014; fringearts.com/the-body-lautrec.

For fuck’s sake, I saw it with my 13-year-old son, and he didn’t even flinch. Deb Miller needs to grow up. If she’s seeing a show about prostitutes, alcoholics, physical disabilities and syphilis, she ought to expect that it’s not going to be pretty. I had my own issues with the show, but moralizing about Lautrec’s milieu really seems like missing the point.

Wow. Did anyone actually read my review? I didn’t say any of this. In my review, which was limited to 150-250 words, I simply re-viewed–looked at the production again. I didn’t attack anyone, my only use of names was to credit the people who contributed to the show and to applaud those I thought were standouts. I felt that I captured the tone and message of the play–the shocking sexual exploitation, objectification, and degradation of women in that culture, and the self-destructive behavior that was prevalent in that circle. I thought that was the point. I said the portrayal was shocking and explicit, because it was; again, I thought that was the creators’ intent, to recreate the demi-monde of 19th-century Montmartre. I did think it was appropriate to give the general public a heads-up about the content, since it clearly is not everyone’s proverbial cup of tea, and I do believe some potential audience members might be offended by the graphic content, so should be forewarned. My only negative comment was that I didn’t find this debased coterie sympathetic–I don’t have sympathy for those who participate in the maltreatment of women, and I think that’s a very feminist statement–which I thought the show was also supposed to be making. I was cited by name in the follow-up interview, though I was not invited to be part of the “dialogue”–which, by definition, should include both sides, so that my review could be represented accurately. I am also concerned that the first line of my review was inadvertently deleted by the editor who posted it: “Can you see beauty in ugliness, or is it just playing in the dirt?” (Lou Reed, “Starlight,” Songs for Drella). That was intended to set the tone, and paraphrased a comment by the creators in the program notes. To misrepresent what I wrote, and to attack me for someone else’s misrepresentation, is, to me, lacking in professionalism, civility, and common courtesy.

I was the editor who inadvertently left out the epigraph, now added to the review: https://phindie.com/the-body-lautrec-aaron-cromie-and-mary-tuomanen-fringe-review-5388/

So, yes, I had not read your article before I got the kind call from Julius, and I was speaking off the cuff with a beer in my hand, so I think we all we coming from different zones on this one. Now, having seen what you wrote, I see that I was mistaken; I think I’d assumed that you were disgusted by the actions of the artists rather than the actions of the characters. Which is, to be fair, a common reaction to disturbing art. Requiem For A Dream, whether or not you like the movie or are able to sit through it, does not condone or glorify the ravages of drug use, it simply reveals them. Nevertheless, I know I’ve heard viewers of the film say, “Why would you do that? Why would you show that?” As though showing it condones it and glorifies it. So hearing about your review second hand, I assumed you were in that camp. Now, having read it, I see that your disgust was not only justifiable, but arguably, solicited by the content of the play we made.

Yes, you’re quite right, there is a lot of content in The Body Lautrec that can disgust on a visceral level. We are not trying to be didactic in showing this — it’s not a Don’t Do Drugs Or Have Sex play — but rather, we’re exposing some painful parts of the human experience that Lautrec’s paintings also explore. And it is meant to be complicated.

To speak to this complication: in the interview, I assert that some of the prostitutes in Lautrec’s life were his friends, but I must say that this is my own non-verifiable opinion, and certainly these friendships must have been extremely complicated since they involved 1) class difference 2) gender difference 3) monetary transactions 4) a difference in the amount of rights, agency and freedom each party enjoyed on a daily basis. We try to show some of that complication in the show. Lautrec pays Kate’s character for sex early in the play, and later tries to pay Gosia’s character to sing him a song when she refuses to comfort him. Is it possible to be friends with someone you also pay for pleasure, in various forms? Maybe not. Or maybe it’s just complicated. Is it possible to be friends with someone that you use in your art? I’ve certainly damaged my own friendships by putting shared experiences in plays. It is very very complicated. So we must necessarily stay clear of being didactic and moralizing in order to allow for this ambiguity, allow each audience member to decide for herself what these unique relationships mean.

Regarding the word “exploitative,” I also see that you never used this word in your review, and that was my confusion. I think it does open up an interesting conversation, though. We’ve all seen plays in which we felt the nudity was not serving the show. When it seems to be about something other than illuminating an aspect of the story, it will be painfully obvious to an audience. We use the word “gratuitous” for this, which can mean not only unwarranted, but also free of charge. This comes back to the point I was making about a woman’s body carrying the idea of money with it — as though a female actress, by standing onstage without clothes on, is giving you something she could charge for. Gratuitous nudity puts the actress in a position where she feels herself monetized, commodified, and part of a transaction that has nothing to do with the story the play tries to tell. So the struggle of Philadelphia’s female performers re-appropriating the body onstage is also a process of de-commodification. In fact, our challenge in The Body Lautrec is doubly difficult because we are looking at characters whose job it is to commodify their bodies, in situations that have nothing to do with transaction — medical examinations, for example — and situations that have everything to with transaction — modeling for artists, selling sex. So complex! But I would argue that a show that does give you that feeling, that ineffable creepy feeling of The Gratuitous, is not art. The director has broken the sacred contract that transactions end at the door. Period.

This is a really long reply, but I think the confusion that began all this was completely worth it for the interesting thoughts and conversations it has sparked. We should all keep talking about this, keep thinking about it, keep unpacking it. I think as artists and audiences we can all work together to keep each other honest, keep each other compassionate. Thanks to you and phindie for creating this opportunity for us all to voice our thoughts on the matter!

All the best, MARY TUOMANEN

Question, Julius: All due respect, if you “realized the cruelty of your piece.” Take it down. Do another article/interview with Mary and Deb, and Wendy maybe and yourself all equally represented. The disclaimer doesn’t really work if you leave the cruel bits of the piece in.

What is going on in the comment section above is just as interesting as the article. Its not fair that Deb was limited to 250 words and you get to go-Tolstoy-long about nudity here. As writers we put our necks on the chopping blocks and sometimes only our editors support us. (Chris Munden has always been nothing but supportive and I love him so much for it).

Deb writes too much for Phindie, She deserves better. Critics need to feel safe to express themselves just as much as artists do on stage.

We expect harsh gruff from the public, or maybe artists close to the work we critique but our own editor? Really? No.

Also on the subject of nudity on stage, you could/should call the actress, Harmony Stempel performing in Human Fruit Bowl tonight at the Club Voyeur, or call the writer of Human Fruit, Andrea Kuchlewska. http://www.humanfruitbowl.com/

Also just on the subject of artist modeling/nudity: I’ve been an artist model on the side for a few years now, and its a profession that is dear to my heart. Every woman should model once in their lives. It would cure-banish all body-issues. But, Jesus, that would be a lot of people at that sit-down interview. Just putting it out there.

I for one, enjoyed the piece very much. It was gutsy, poignant, and delivered to my every sense a rush of nausea that was at once gross and holy. Mary, Aaron, and the rest: Thank you for The Body Lautrec, and for inviting us to share in your honest exploration of the painter’s world, raw and brutal though it was.

“If he does not exhibit his body, but annihilates it, burns it, frees it from every resistance to any psychic impulse, then he does not sell his body but sacrifices it. He repeats the atonement; he is close to holiness.” Jerzy Grotowski (1968)

Ok–I can’t shake this yet—-I should be working on a review for Phindie because its still technically Fringe, man! But this article/disclaimer it troubles me so much when you say:

“Dr. Miller pointed this out to me, and I did not believe her. It was only after multiple people had either approached me about this that I realized the cruelty of the piece.”

I am sorry this is just a scary statement to read.

Deb approached you saying that you 1) hurt her feelings as her editor, or 2) damaged her work and 3) you did not believe her? And 4) you crumble only under peer pressure? 5) Discussed the review with the director, Mary, who openly admits in the comment above she didn’t even read the review at the time the discussion occurred? (Let Mary read it first ) or 6) Don’t let Mary read it. Yet. You can’t just run to the artist/company to discuss reviews.

Doing so, approaching companies about reviews we write could be potentially damaging to their work as artists. The reason that there is a division between artists and critics, I think is because criticism can work against the artist process. We judge, we evaluate, we offer context as critics for the audience deciding on what to see this weekend.

Actors/artists train for years, work for years trying not to judge, not to evaluate, not to assess, not to rationalize their work while they are on stage. Art and criticism can be polar opposites so don’t just call up companies to discuss reviews. No, in my opinion, bad form. If they approach you, different story all together. But never approach them with what you feel to be a disparaging review about them.

When I was a professional actress, I refused to read my reviews till after the run. I hated to read them because they would make me get too much in my head, and they altered my perception of the play. And I only wanted to listen to my director anyway. Listening to a critic/reading a review can be like having too many cooks in the head of an actress, you know what I mean?

Potentially dangerous. Other actors had stronger stomachs than I did, and they would read them, but not me. I couldn’t, or wouldn’t.

You’re just lucky Mary was fine with it.

Thank you for reading & now back to that review I was working on—- for you (Phindie)–<3 J