After the horrifying 9/11 terrorist attacks, America understandably lost its collective mind. We were hurt, mad, and in desperate need of some sort of leveling of the scales. We almost immediately put our troops into action. Doesn’t matter where, we just needed to get some catharsis, whatever form that may take. We wanted to round up anybody and everybody that was connected to the attacks, operating under a very loose interpretation of the term “connected.” With this initiative came the Guantanamo Bay detention camp (still open, BTW), where we held those who were deemed the most dangerous people in the world. Detainees were imprisoned indefinitely and stripped of a right to trial while never being charged with a crime, while torture and degradation of inmates were disgustingly commonplace practices.

After the horrifying 9/11 terrorist attacks, America understandably lost its collective mind. We were hurt, mad, and in desperate need of some sort of leveling of the scales. We almost immediately put our troops into action. Doesn’t matter where, we just needed to get some catharsis, whatever form that may take. We wanted to round up anybody and everybody that was connected to the attacks, operating under a very loose interpretation of the term “connected.” With this initiative came the Guantanamo Bay detention camp (still open, BTW), where we held those who were deemed the most dangerous people in the world. Detainees were imprisoned indefinitely and stripped of a right to trial while never being charged with a crime, while torture and degradation of inmates were disgustingly commonplace practices.

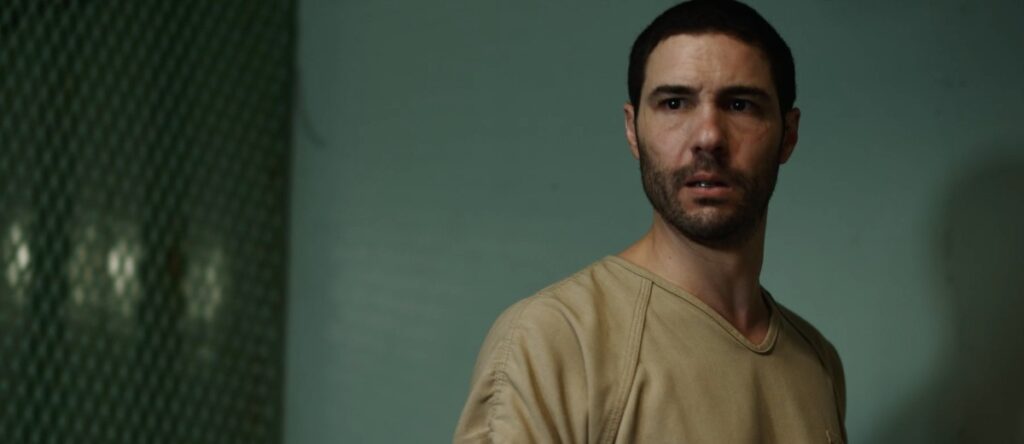

The Mauritanian tells the true story of Mohamedou Ould Slahi (Tahar Rahim), a man who was held at Guantanamo for 14 years without a single charge ever being leveled at him. Based on the book that Slahi wrote about his experience, the film follows his life as a prisoner, as well as the experience of Nancy Hollander (Jodie Foster), the lawyer who worked with Slahi to affirm his right to all the judicial processes stripped from him by the US government. His case is a controversial one to take, and Hollander chooses to handle it not because she believes in his innocence, but because she believes in his right to profess his innocence. At her side is Teri Duncan (Shailene Woodley), an associate who also believes in Slahi’s plight, and whose emotional investment in the case puts her at slight odds with Hollander’s more clinical approach.

As the excesses of Guantanamo Bay start to become public knowledge, pressure mounts to start processing the prisoners in some type of way. “There’s a backlog needs clearing” advises a suit to Stuart Couch (Benedict Cumberbatch), a military prosecutor dispatched to level charges at Slahi. Couch has a personal connection to a victim of the attacks, and is emotionally incentivized to bring justice to those responsible. As Couch, Hollander, and Duncan each dig into Slahi’s case, much of what they profess to understand is challenged by circumstance, while Slahi, whose hands are literally and figuratively tied, taps into an uncommon strength to keep the faith that one day, he may once again be free.

The direction by Kevin Macdonald (The Last King of Scotland) is sharp and workmanlike. This film looks like your standard early-2000s thriller, which is appropriate given the time frame in which much of it is set. Yet despite the sharp look, there are some pacing issues that lead to an overall uneven feel. At points the film is positively gripping. At others it feels like wheels are being spun just to cover perfunctory ground. A mid-film sequence that aims to show Slahi’s experience being tortured by guards takes the tone of a Nine Inch Nails video which, despite the gut-wrenching truth behind it, ends up feeling silly. It’s a strange miscalculation, but luckily it’s only a short aside.

For every lapse, the film is quick to correct itself and get back on track, but oftentimes this leads to new faults. Silly dialogue (“This dude is the Al Qaeda Forrest Gump — everywhere you look, he’s there”) and excessively didactic messaging (Foster’s Hollander speaks almost entirely in literal declarations of the film’s theme) prevent this competent picture from becoming the prestige piece it hopes to be. Even with these odd choices occurring regularly, the film shines in the department of performance. Foster is great, as is expected, even when she’s chewing on goofy dialogue. Cumberbatch too, is able to evoke strong emotion out of a character who is a non-emotive military type. The real standout is Tahar Rahim, who is able to bring a level of depth and humanity to Slahi upon which the entire movie confidently rests. It’s a sturdy, occasionally uneven film, but Rahim’s performance is rock solid, and worthy of wide praise (fans of his work here should check out Un Prophéte, a stellar prison drama that also showcases his tremendous powers as an actor).

The film also shines in the way it demonstrates the empathy it professes. Every side of Slahi’s case is motivated by people trying to the the right thing. Even in the damp, concrete walls of Gitmo it’s made clear that few are getting off on Slahi’s terrible treatment. The cruel decisions being made began with the best intentions, and came from a nation in a state of serious hurt. The film treats this as an explanation, not as an excuse, which is important for keeping the theme of humanity strong throughout. People can be good and bad, not good or bad, and this story would be much weaker if it lived in a black and white world (a world of fiction). I would assume that a lot of this empathy is mined directly from Slahi’s writings — he seems like a remarkable guy.

The Mauritanian is very worth watching, but it suffers from the curse of “its strength is its weakness” in that it feels like it exists just a few years too late. There’s little here that most people don’t know about the now infamous Gitmo, and I get the sense that the narrative is indeed trying to be educational in the way it presents the story. At the same time, the abuses of power demonstrated by the United States in our 9/11 response have never been answered for, and with each passing day it seems that government transparency is an increasingly opaque and archaic notion. As we blindly roll over and cluelessly beg for elected officials to erode the rights of American citizens, a film like The Mauritanian can exist to remind us that power, once seized, is hardly ever relented without intense pressure, and that even the most well-intentioned rule can be perverted into something inhuman.

The Mauritanian is now available to own on digital and available on Blu-Ray & DVD on May 11th.