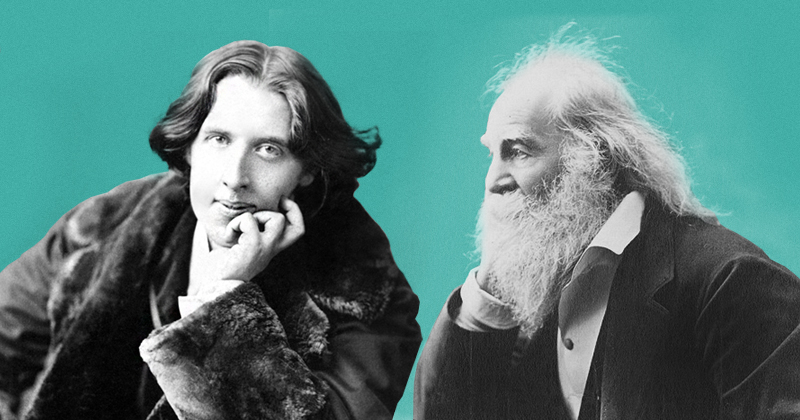

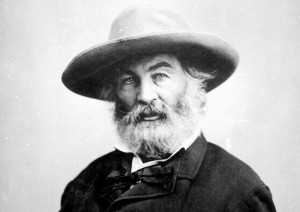

The last big Whitman at 200 event was Tom Wilson Weinberg’s Oscar Visits Walt, a musical play about the time when Oscar Wilde, then 27 and on a United States tour, visited 62-year-old Walt Whitman at the Whitman family home on Camden Stevens’ Street.

The last big Whitman at 200 event was Tom Wilson Weinberg’s Oscar Visits Walt, a musical play about the time when Oscar Wilde, then 27 and on a United States tour, visited 62-year-old Walt Whitman at the Whitman family home on Camden Stevens’ Street.

The event was held at Philly AIDS Thrift @ Giovanni’s Room on a dark and stormy night. About fifteen people, most of them press, crammed into the tiny store, some straddling the famous narrow staircase as Andrew Boyask, dressed as Whitman in a fine leather ‘western’ hat, lingered by the door of the store waiting for Oscar to knock.

Tom Wilson Weinberg, dressed in appropriate theater black sans a string of old pearls he said his mother bequeathed to him (rather than to his two brothers) was his gracious self as his partner of many years, John Whyte, a physician by profession, held copies of the script in order to prompt the actors should they forget a line or two. (As it turned out, there were not many corrections but when they did occur they seemed to add a bounce to the play).

It didn’t take long for me to see why Weinberg cast Boyask as Walt. With his bright, steady eyes and confident countenance, Boyask was the perfect Whitman. The more verbose in love with himself 27-year-old Oscar was the more conversationally fluid of the two characters. Caleb J. Tracy, as Oscar, fit Whitman’s historic description of Wilde as a “big, splendid boy.” Tracy had Wilde’s mannerisms down pat, his aesthete poses by the mantelpiece, the way he presented Walt with a lily, the elegant hand and foot gestures. And then there was Oscar’s walking stick, a cane topped with a bright white duck’s head. It was enough to make me want to read up on Wilde the next day. In real life Whitman was anything but a conversationalist. He spoke in short, ungrammatical bursts. Wilde was a snob. Weinberg’s Walt is polished and grammatical.

“Wilde didn’t travel to Camden to talk about gender roles or belles letters,” The New Republic reported in 2014. “The writer was still years away from becoming the author whose peerlessly witty plays are still staged today. What drew him to Whitman’s home was the opportunity to discuss fame. He wanted to listen to the singer of ‘Song of Myself’—an older man with inexhaustible energy, despite his infirmity, for self-promotion.“

When Wilde was a student at Oxford he may have been an aesthete with an obsessive penchant for decorating his rooms, but he was no slouch when it came to defending himself. Once when he was bullied by two or three thuggish classmates he sprung into action, throwing one bully on the floor and the other one against the wall. This gilded lily was loaded with dynamite.

In Oscar Visits Walt, Wilde tells Walt that he is not attracted to him in a husband like way. Like most twenty-something men (especially in the gay world), age consciousness is always a front and center issue. Generally it is always younger people who are the first to point out age differences when in mixed company. Oscar, of course, is jumping the gun here because at this point Walt hasn’t really made a pass at him. Oscar is just protecting himself, setting limits “just in case” ole Walt gets some funny ideas.

In Oscar Visits Walt, Wilde tells Walt that he is not attracted to him in a husband like way. Like most twenty-something men (especially in the gay world), age consciousness is always a front and center issue. Generally it is always younger people who are the first to point out age differences when in mixed company. Oscar, of course, is jumping the gun here because at this point Walt hasn’t really made a pass at him. Oscar is just protecting himself, setting limits “just in case” ole Walt gets some funny ideas.

Ironically, Oscar certainly doesn’t fit Walt’s ideal of the sexy man-boy. None of Walt’s male comrades in Camden and elsewhere were as flamboyant, elegantly verbose and as ‘lily limping’ as Oscar was. They were working class man-boys, uneducated, blue collar ruffians that in many ways might be compared to the opioid driven knapsack-carrying vagabonds with dirty hands that one sees on the streets of Philadelphia today. Most of them were almost certainly heterosexual.

Yet it is fascinating to see how Weinberg draws out these two men, who are not really each other’s “type,” and then makes it believable that they are irresistibly drawn to one another so that a quick rendezvous in Walt’s bedroom is a cosmic “must do.”

Of course, for the “dirt” on what Walt liked to do in bed all you have to do is read Edward Carpenter’s writing on the subject. Carpenter spells out the details clearly. In some descriptions of what Walt liked to do the reader is told that Walt behaved in an authentically loving manner rather than in a feverish succubus fashion. American poet Allen Ginsberg, who claimed to be Walt Whitman’s poetic successor, was saddled with the latter charge.

The two men emerge from Walt’s bedroom, Oscar first, then Walt, both of them tucking in or rearranging their shirts. Oscar has less to rearrange which to me indicated that Weinberg did his Carpenter homework.

Sex may have happened between the two men or it may not have. We will never know. Weinberg’s play is exceedingly clever and has its brilliant moments; the musical lyrics—many of which come straight from Whitman and Wilde while others come from Weinberg—delight the ear, however when Oscar repeatedly digs at Walt for his attitudes towards black Americans the work enters preachy, ideological waters. One reference to this would have been sufficient; sometimes less is more.

Oscar Wilde was a truly great man whose life and work speaks to many issues—some controversial– current today.

In 2011, The Guardian reported, “A kiss may ruin a human life,” Oscar Wilde once wrote. It can also ruin the stonework of a tomb, judging by the extraordinary graffiti – kisses in lipstick left by admirers – that for years have been defacing and even eroding the massive memorial to the Irish dramatist and wit in Paris’s Père Lachaise cemetery.

In 2011, The Guardian reported, “A kiss may ruin a human life,” Oscar Wilde once wrote. It can also ruin the stonework of a tomb, judging by the extraordinary graffiti – kisses in lipstick left by admirers – that for years have been defacing and even eroding the massive memorial to the Irish dramatist and wit in Paris’s Père Lachaise cemetery.

In the 1990s women in fresh red lipstick began the cult practice of kissing Wilde’s tomb or writing messages on the tomb with lipstick. This caused the stone to be damaged. Eventually a glass barrier was erected around the tomb to protect Wilde from his fans.

In 2015, The New York Times Arts Beat reported that:

“Efforts to stage a gay-themed play about Oscar Wilde in Moscow foundered in June on the Russian government’s hostility toward homosexuality and the use of foreign funds for artistic productions. Now, the New York-based theater company that was partnering in that project will hold a one-night-only, impressively cast benefit reading of the play in October in Manhattan to focus attention on what it calls Russia’s suppression of the rights of gays and lesbians.’

The topic of Oscar Wilde is also big on Catholic lecture circuits. This is due in part to Wilde’s deathbed conversion to Catholicism. Joseph Pearce, author of The Unmasking of Oscar Wilde, writes:

I’m very much influenced, or motivated, by the provocations of errors in recent biographies of Wilde. Ellmann’s biography, Oscar Wilde [Penguin, 1988] was considered, blithely, the definite biography of Wilde. Part of that is Ellmann’s academic reputation; also Oscar Wilde is large and substantial. Lots of research has gone into it. But Ellmann gets all the facts and then mixes them up in such a way as to not clarity, but to muddy the waters. His is a postmodern biography. Wilde is presented as a relativist with no sense of good and evil. On the contrary, Wilde’s art shows a consistency of objective morality, specifically Christian morality”

In The Long Conversion of Oscar Wilde, Andrew McCracken writes:

“As Wilde lay dying on his bed in Paris, Robbie Ross called in a priest, an English Passionist, Father Dunne. Wilde was given conditional Baptism and was anointed. For a short time he emerged from delirium into lucidity, and Father Dunne, examining him, was satisfied that Wilde freely desired reception into the Church. Wilde died a Catholic on November 30.

The poet’s great antagonist, the Marquis of Queensberry, died in the same year. On his deathbed, he too was received into the Catholic Church. And the object of the poet’s self-destructive passion, Lord Alfred Douglas, became a Catholic in 1911 and remained firm in the Faith until his death, though his later writings betray a conservatism that is distasteful and uncharitable.“