If you would not be forgotten, as soon as you are dead and rotten, either write things worth the reading, or do things worth the writing.

—Benjamin Franklin

Throughout its history, Philadelphia has been a center for writing and publishing. The list of authors who have walked the city’s streets reads like a who’s who of American writing: Ben Franklin, Edgar Allan Poe, Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, John O’Hara, and James Michener, to name but a few. This writing tradition continues to this day, with numerous small presses printing the work of the city’s flourishing literary scene and such authors as Jennifer Weiner and Jonathan Franzen using Philadelphia as a backdrop to their bestselling novels.

Throughout its history, Philadelphia has been a center for writing and publishing. The list of authors who have walked the city’s streets reads like a who’s who of American writing: Ben Franklin, Edgar Allan Poe, Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, John O’Hara, and James Michener, to name but a few. This writing tradition continues to this day, with numerous small presses printing the work of the city’s flourishing literary scene and such authors as Jennifer Weiner and Jonathan Franzen using Philadelphia as a backdrop to their bestselling novels.

Philadelphia was founded in 1682 and it took just three years for the city to get its first printing press. As the city grew to become the colonies’ preeminent metropolis, its Quaker religious printers were joined by a slew of newspapers, magazines, and political presses, printing writing in English, German, and other languages. In 1723, a young printer’s apprentice from Boston stepped into this burgeoning literary scene.

Ben Franklin is better known today as a founding father and scientific mind (as well as the founder of many leading Philadelphia institutions), but he began his career and first made a name and fortune for himself as a writer and publisher. He began publishing his most enduring work, Poor Richard’s Almanac, in 1733. For the next twenty-five years, Franklin’s well-remembered wordplays and aphorisms (including the epigraph that begins this article) graced the Almanac’s pages.

Franklin’s presses also released the first novel printed in North America, Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded (1740), by English author Samuel Richardson. At first, European authors dominated this new literary form, but it did not take America long to catch up. Philadelphian Charles Brockden Brown became the first major novelist of the nascent country, publishing a series of romantic gothic novels that earned him the moniker “father of the American novel” and heavily influenced Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and a long list of transatlantic writers.

As Philadelphia’s status in the new Republic grew, so too did its position in the American publishing world. By the early nineteenth century, the city was home to numerous newspapers, political presses, magazines, and literary journals.

The nation’s finest writers plied their trade in Philadelphia’s publishing houses. Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) was editor of Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine, which merged with another publication to become Graham’s Gentleman’s Magazine in 1840. It was in the latter that he published his “Murders in the Rue Morgue,” now considered the first ever detective story.

Poe lived a decidedly peripatetic life. Born in Boston, he lived in Scotland, London, Virginia, Baltimore, and a few other places before arriving in Philadelphia. He resided in several houses while in the City of Brotherly Love, one of which is preserved as the Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site at Seventh Spring Garden Street in Northern Liberties. Poe wrote or published many of his most famous stories during his five relatively stable years in the city, including “The Tell-Tale Heart” and “The Fall of the House of Usher.”

Then as now, writing was a difficult way to make a living. Just after he left Philadelphia, Poe published his most successful poem, “The Raven.” He was paid just $9 for it. But one Philadelphia writer who did find financial reward at this time was Poe’s friend George Lippard.

Born in Chester County, just south of Philadelphia, and raised in Germantown (now within city limits) and upstate New York, Lippard was a lifelong champion of the common man, having spent part of his young life penniless and homeless. Following the influence of Brockden Brown and his friend Poe, Lippard published popular historical romances, which he called legends. His most famous work, The Quaker City, or the Monks of Monk Hall (1845), was a bitingly satirical portrayal of Philadelphia’s upper classes. The novel won Lippard both notoriety and fortune, selling tens of thousands of copies to become the most successful American novel ever until the release of Harriet Tubman’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

The most prominent physical monument to Philadelphia’s rich publishing history is the grandiose Curtis Center on Washington Square (Walnut Street between Sixth and Seventh streets), built in 1893 as the headquarters of the Curtis Publishing Company. Curtis published such popular periodicals as Ladies’ Home Journal and the Saturday Evening Post. Still an active office building, the Curtis Center is worth a visit to see the impressive Dream Garden glass mosaic, commissioned by the company from the Louis C. Tiffany studios and based on a painting by Philadelphia artist Maxfield Parrish.

Among the leading writers who called Philadelphia home during its nineteenth century publishing boom was Mark Twain (1835-1910), perhaps the first great American novelist, who worked briefly as a typesetter for the Philadelphia Inquirer. Louisa May Alcott was born in Germantown before moving to Boston, the setting for her much-loved Little Women (1868). Owen Wister, whose 1902 novel The Virginian is credited as the progenitor of frontier western literature, was a scion of a prominent Philadelphia family.

The history of writing in Philadelphia is inscribed in poetry as well as prose. Visitors entering the city via I-76 West pass over the Walt Whitman Bridge, named for the great American poet. Walt Whitman spent his last two decades in neighboring Camden, New Jersey, and visited Philadelphia regularly. He prepared the last four editions of his free-verse magnum opus, Leaves of Grass (first edition, 1855), while in Camden. Visitors to the city today can find Whitman’s grave and last residence.

Other great American poets also called Philadelphia home. Ezra Pound (1885-1972) and William Carlos Williams were friends while students at the University of Pennsylvania. Ezra Pound’s father was an assayer at the Philadelphia mint, and the poet spent most of his youth and young adulthood in the area. Although his career is overshadowed by his later politics (which included antisemitic and profascist writings), Pound was an influential poet of the “lost generation” of American writers between the two world wars. His friends and admirers included T.S. Elliot (as an editor, Pound helped shape Eliot’s “The Waste Land”), James Joyce, and Ernest Hemingway.

Pound was also longtime friends with William Carlos Williams, who he met while the two were students at the University of Pennsylvania. A practicing doctor, Williams is remembered for his plainspoken, staunchly American verse.

Pound and Williams were both admirers of Marianne Moore (1887-1972), another Modernist poet who spent a chunk of her life in Philadelphia. An alumnus of Bryn Mawr College, Moore won the Pulitzer Prize for her 1951 Collected Poems. Her library and living room are lovingly preserved the Rosenbach Museum & Library near Rittenhouse Square, where visitors can see 2,500 of her personal objects in their original layout.

The Rosenbach Museum is housed in the former home of Philip and A. S. W. Rosenbach, renowned dealers in rare books and manuscripts. The brothers helped assemble many of the nation’s finest private libraries, and their impressive personal collection forms the core of the museum’s holdings and includes the three oldest extant books printed in the Americas, the only surviving copy of Franklin’s first Poor Richard’s Almanac, and James Joyce’s handwritten manuscript to Ulysses.

By the early twentieth century, when the Rosenbach brothers were amassing their rich collection, Philadelphia had long since been surpassed as a center for American publishing, politics, and culture by its neighbors to the north and south and burgeoning metropolises to the west. The city soon began a decline in population and prestige that would continue until the renaissance of recent decades. This reality was reflected in the work of the best Philadelphia writers of the early 1900s, as the city spawned a slew of fine hard-boiled novelists.

Chief among them is William McGivern, author of forgotten classics The Big Heat (1953) and Rogue Cop (1954), both of which were adapted into popular movies; the film version of the former is seen as one of the classics of American film noir. McGivern wrote most of his 20 novels while a reporter for Philadelphia newspapers and most of them take place in recognizably Philadelphia locale. The same is true for the novels of John McIntyre, whose bestseller Steps Going Down (1936) was one a half dozen works of gritty fiction to use the city as a backdrop. Philadelphia was also the original setting for the hard boiled novel Down There (1956), by local Jewish American writer David Goodis. Relocated to Paris, the book was filmed as cinematic classic Shoot the Piano Player by acclaimed French new wave director François Trauffaut.

Philadelphia was also home to more conventional literary greats of the last century. Best known today for his devastating first novel An Appointment in Samarra (1934), John O’Hara — whose indelible links with nearby Pottsville, Pennsylvania, make him as Philadelphian as Yuengling Lager, the city’s favorite beer — was for a time viewed as America’s preeminent novelist. As ever-present a part of the Philly’s social life as his hometown product is today, O’Hara was a rival to Hemingway, Steinbeck, and Updike, and received deserved praise from each of these literary luminaries.

James Michener (1907-1997), dismissed by Hemingway as “that gifted Philadelphia writer,” grew up in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, just outside the city, and spent most of his life in the area. His epic bio-geographies of such places as Hawaii (1959), Chesapeake (1978), Alaska (1988), and the Caribbean (1989) are still widely read. Named in honor of the author, the James A. Michener Museum in Doylestown has an unrivaled collection of Pennsylvania Impressionist paintings as well as a display room dedicated to Michener, featuring items from his office, his books, and his papers.

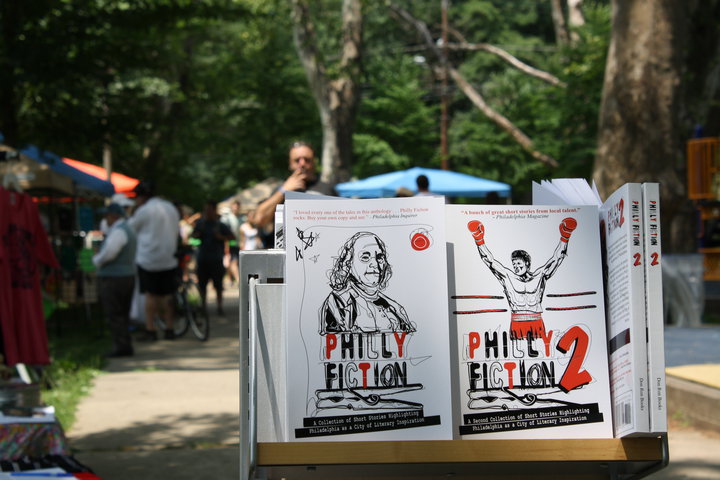

Philadelphia’s writing legacy continues to the present day, supported by a new cadre of literary journals and publishing projects. Philadelphia Stories, a free quarterly lit mag found in book stores and coffee shops around the city, has been publishing fiction and essays by the region’s best writers since 2004. Another lit mag, Apiary Magazine, is more recent but of similar quality. Two acclaimed anthologies co-edited by the author of this piece, Philly Fiction (2006) and Philly Fiction 2 (2009), collected short stories set in the city and written by local authors (a third, South Philly Fiction, is forthcoming). The city’s legacy of hard boiled fiction continued in an anthology of Philly-set tales, Philadelphia Noir (2010).

Philadelphia has also been the locale for recent blockbusters. Critical darling Jonathan Franzen set much of his breakthrough third novel The Corrections (2001) in and around Philadelphia; several scenes from his hit follow-up Freedom (2010) also take place here.

The city has been especially blessed with writers in the genre of breezy introspective writing known somewhat dismissively as “chick lit.” Sarah Dunn, a columnist for a Philly alt-weekly before becoming a successful TV writer, used the city as the backdrop for her bestselling first novel, The Big Love (2005). University of the Arts professor Elise Juska wrote Getting over Jack Wagner (2003), the first in a string of successful female-centric novels.

Most famous in this genre is Jennifer Weiner, a former Gen X columnist and features writer for the Philadelphia Inquirer, who has used the city as the setting for her bestselling novels, beginning with her 2001 debut Good in Bed. Her successful second novel In Her Shoes (2002) was adapted into a hit movie starring Cameron Diaz and filmed on location in Philly.

Other writers have explored unsavory aspects of city life: Steve Lopez’s Third and Indiana (1994) takes place in the Philadelphia badlands of North Philly. (Lopez’s later writings about schizophrenic jazz bassist Nathaniel Anthony Ayers inspired the film The Soloist, which stars Robert Downey Jr. as the author). Philadelphia journalist Solomon Jones chronicles down-and-out tales of addiction and poverty in the city’s African American communities in his novels, the latest of which, The Last Confession, was released in November 2010.

As the city’s presses keep turning and its writers’ pens keep scribbling, a rich literary tradition continues in the City of Brotherly Love.

Places to Visit

Franklin Court

site of Benjamin Franklin’s home and print shop

Market St. between Third and Fourth sts.

800-537-7676

nps.gov.inde

Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site

Seventh and Spring Garden sts.

215-597-8780

nps.gov.edal

Walt Whitman House

330 Mickle Blvd., Camden, NJ

856) 964-5383

nj.gov/dep/parksandforests/historic/whitman

Rosenbach Museum & Library

2008-2010 Delancey Pl

215-732-1600

rosenbach.org

James A. Michener Art Museum

138 S. Pine St., Doylestown, PA

215-340-9800

michenermuseum.org

Published by Morris Visitor Publications as “Literary Legacy: An Account of the City’s Bookish History”. Rights reverted to author.

Good general history but the piece falls apart when you write about contemporary Philly writers.

Yes. What would you add?

I’m looking for a serious writers group that will discuss Plotting and Craft. Are there any you know of? Thank you. Ninamckissockauthor@gmail.com