Early publishing in Philadelphia has a rich and storied history. William Penn founded Philadelphia in 1682; within three years the nascent town had its first printing press. The first American publication was printed in Massachusetts in 1639, so in publishing — unlike in many other endeavors in America — Philadelphia cannot claim precedence. Nevertheless, it did not take long for the city to establish itself as a major printing center.

Publishing in Philadelphia began as an enterprise of Quaker meetinghouses, which printed mainly religious texts. The city’s first printer, William Bradford, was forced out of town when he published a tract critical of the Quakers. Bradford relocated to New York and began a successful printing career there, but sent his son Andrew back to Philadelphia in 1713 to set up the city’s first independent press. At first, the younger Bradford printed theological works using equipment rented from the Quakers, but he soon acquired his own press and began to publish secular works. The American Weekly Mercury, the newspaper Andrew Bradford began in 1719, was Philadelphia’s first and the third in the colonies. The Bradford family continued to publish newspapers and other texts for generations, and their operations in New York and Philadelphia made them one of the most distinctive and influential families of printers on the continent, but it was a young printer and editor from Boston who established Philadelphia as the premier city for publishing.

Benjamin Franklin, Philadelphia’s most famous resident, is perhaps best known as a scientist and “Founding Father,” but his first and principal career was as a printer and publisher. (In colonial America, there was little demarcation between printing and publishing, and these trades were often combined with bookselling). Born in Boston in 1706, Franklin apprenticed in the printing shop of his brother James from the age of 12. He left Boston at age 17 and used his printing skills to find work in Philadelphia and London. By 1728, Franklin had settled in Philadelphia and owned his own printing press. Franklin’s easygoing writing style and shrewd sense of what people wanted to read soon made his publications the finest in the colonies. The most famous was Poor Richard’s Almanack, edited by Franklin from 1733 to 1758, which sold over 10,000 copies a year across the continent.

Although he retained an interest in publishing throughout his life, Franklin retired from the trade in 1748 to give time to his many other pursuits. By this time, however, Philadelphia’s printing industry was firmly established, with six printers and three newspapers serving a population of about 10,000. Over the next three decades, more than 40 printers would set up shop in Philadelphia. Published material included religious texts (the first work released from Franklin’s printing press was probably the Psalms of David), textbooks, encyclopedias, newspapers, almanacs, magazines, government documents, and political tracts.

Franklin’s company released Pamela, the first novel printed in America, in 1740. Many of the most popular works of the time were pirated reprints of British literature and plays. (Copyrights were considerably harder to enforce in those days.) Because transportation costs were so prohibitive in 18th-century America, local booksellers generally printed their own version of these books. It was not until the first decades of the next century that Philadelphia and New York were able to achieve dominance in the publication of literature.

However, Philadelphia dominated the field of medical and scientific publishing quite early. The American Philosophical Society, the nation’s oldest scientific academy, was founded in Philadelphia in 1743, and the city was home to many scientific luminaries, including physician Benjamin Rush and, of course, Ben Franklin. By 1776, there were 18 presses in Philadelphia printing medical texts. When the city began to lose its position in some fields of publishing to New York in the mid-1800s, many Philadelphia publishing houses focused increasingly on medical publishing. This focus continues today.

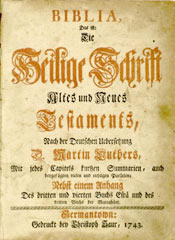

Philadelphia saw a huge increase in population beginning in the middle of the 18th century. Many of its new residents were of German origin. By the 1770s, an estimated one-third of the city’s population was German speaking. German-language issues accounted for 15% of all titles published in Philadelphia from 1740 to 1776. The principal publisher of German literature in Philadelphia was Christoph Sauer (a name he anglicized to Christopher Sower on his English-language releases). Sauer’s sons and grandsons continued to print his newspaper, one of Philadelphia’s most popular—in any tongue—for many years after his death in 1758. Sauer’s best-known publications were prayerbooks and Bibles. His German-language Bible of 1748 was the first European-language Bible printed in America. (The first English-language Bible in America, released by Robert Aitken in 1782, was also printed in Philadelphia.)

Philadelphia saw a huge increase in population beginning in the middle of the 18th century. Many of its new residents were of German origin. By the 1770s, an estimated one-third of the city’s population was German speaking. German-language issues accounted for 15% of all titles published in Philadelphia from 1740 to 1776. The principal publisher of German literature in Philadelphia was Christoph Sauer (a name he anglicized to Christopher Sower on his English-language releases). Sauer’s sons and grandsons continued to print his newspaper, one of Philadelphia’s most popular—in any tongue—for many years after his death in 1758. Sauer’s best-known publications were prayerbooks and Bibles. His German-language Bible of 1748 was the first European-language Bible printed in America. (The first English-language Bible in America, released by Robert Aitken in 1782, was also printed in Philadelphia.)

By the mid-1700s, Philadelphia’s population had surpassed that of Boston. Its accessible location at the center of some of the most fertile land in all the colonies made it the premier city in America. As revolutionary fever grew throughout the continent, it was only natural that Philadelphia became a center for national ambitions. The First Continental Congress was held in Carpenter’s Hall, Philadelphia, in 1774; the Declaration of Independence was drafted by Jefferson and edited by Franklin and his companions in Philadelphia in 1776; and, except for a nine-month period of British occupation in 1777–1778, Philadelphia was the seat of American government for the duration of the War of Independence. Philadelphia also served as the capital of the United Stated from 1790 until 1800, when construction of Washington D.C. was sufficiently complete. As the center of American politics for so many years, Philadelphia was home to many political publications. Before Independence, pamphlets criticizing British policies were a common product of Philadelphia printing presses. During its tenure as the nation’s capital, the city’s newspapers were numerous and vocal, and political tracts espousing either Federalism or Jeffersonian Republicanism were common.

In 1800, Philadelphia lost its status as the nation’s capital, but its publishing industry was the best in the United States. The next few decades saw a remarkable growth in publishing. About 70,000 books rolled off the Philadelphia presses in 1800; by 1820, this figure was closer to 500,000. This growth was spearheaded by a new generation of printers; the most important was the Irish-born Philadelphia publisher Matthew Carey. Carey is often called the “father of modern publishing.” He reorganized the industry, improved distribution of books, and introduced modern notions of book publicity. Carey’s business grew so rapidly that he began to hire specialists to handle different aspects of publishing. He was probably the first American publisher to hire a full-time proofreader, a trade that became well established as publishing houses grew in size. The company that Matthew Carey started continued under the guidance of his colleagues and heirs for over 200 years, most recently as Lea & Febiger.

Philadelphia publishing pioneers like Ben Franklin and Matthew Carey helped establish the industry in America, but their successors were unable to retain the city’s preeminence in the trade. By the middle of the 19th century, New York was the industry’s center. Factors underlying this reversal of fortunes, which coincided with New York’s rise as the nation’s economic powerhouse, are complex and numerous. But despite losing ground to its northern neighbor, Philadelphia upholds the legacy of its early printers, remaining a major player in publishing, especially in the well-established disciplines of science and medical publishing. Philly Fiction, a collection of short stories highlighting Philadelphia as a city of literary inspiration published in 2006 by Don Ron Books, continues the proud history of publishing in the City of Brotherly Love.

Further Reading:

Anton Chaitkin “The American Prometheus, Part I: Who Made the United States A Great Power?” New Solidarity. 1 August 1986. page unknown

John L. Dusseau. An Informal History of the W. B. Saunders History: On the Occasion of Its Hundredth Anniversary.Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company, 1988.

Daniel Sean Kaye. “Historic RittenhouseTown: Shows How to Make Paper and More.” Ticket. July 30/31, 2003. p. 2.

Edmund S. Morgan. Benjamin Franklin. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

Gary B. Nash. First City: Philadelphia and the Forging of Historical Memory. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002.

Carlin Romano. “Where have all the authors gone?” Philadelphia Inquirer. 2 Jan 2000. page unkown

John Tebbel. A History of Book Publishing in the United States. (4 volumes) New York: R. R. Bowker Company, 1972.

John Tebbel. Between Covers: The Rise and Transformation of American Book Publishing. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

John Tebbel; Mary Ellen Zuckerman. The Magazine in America, 1741–1990. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Russell F. Weigley, ed. Philadelphia: A 300-Year History. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1982.

Thomas M. Whitehead, Issue Editor. Drexel Library Quarterly, July 1976, Vol. 12, No. 3. Aspects of Publishing in Philadelphia, 1876–1976.

Hi my name is Wayne T Bryson. My Family going back the 1850s were printers in Philadelphia on N 6th st.

John B Bryson, A C Bryson and Company and James H Bryson were all printers in the area located at where

the Federal Courthouse is today. I was wondering if you had any relevant information on these operations

Thank you

Wayne T Bryson

I have Mrs Rogers Cook Book published by Arnold and Company Philadelphia. no date’

anyone have an Idea??