Meet Leonard Pelkey, the flamboyant teenager who managed to touch the lives of every person in his small Jersey shore town. He helped the neighborhood widows get their groove back. His presence allowed the old man who runs the clock shop to reconcile his guilt over the gay son he disowned, long dead of AIDS. He even taught a hardboiled detective to—gasp—appreciate Shakespeare. All it cost him was his life.

Meet Leonard Pelkey, the flamboyant teenager who managed to touch the lives of every person in his small Jersey shore town. He helped the neighborhood widows get their groove back. His presence allowed the old man who runs the clock shop to reconcile his guilt over the gay son he disowned, long dead of AIDS. He even taught a hardboiled detective to—gasp—appreciate Shakespeare. All it cost him was his life.

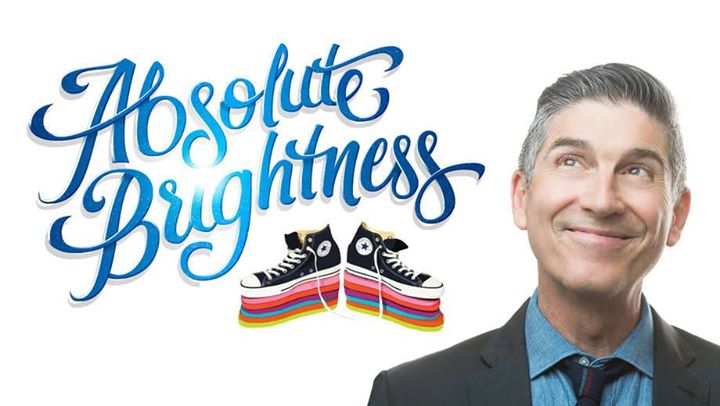

That is the surely unintended but nakedly apparent subtext of THE ABSOLUTE BRIGHTNESS OF LEONARD PELKEY, a well-traveled solo play written and performed by James Lecesne, currently taking up residence at Philadelphia Theatre Company’s Suzanne Roberts Theatre. Lecesne—perhaps best known as the co-founder of The Trevor Project, an organization devoted to preventing LGBTQ teen suicide—might have set out to tell the uplifting tale of an iconoclastic youth who marched to the beat of his own drum, whatever the price. The regrettable outcome, however, is merely the latest in a long line of gay tragedies, where living out loud is met with a gruesome end.

We never actually meet fourteen-year-old Leonard, who’s already at the bottom of lake as the slight and snappy play begins. But we get a sense of the kind of kid he was. “Leonard was totally weird,” intones his cousin Phoebe, her voice dripping with teenage ennui. “When weird goes too far, it just becomes bizarre.” Too far, in this case, becomes a litany of familiar queer mannerisms: Wears make-up. Does a killer Julie Andrews impersonation. Twirls around the mall like he’s auditioning for Maria in West Side Story. The pièce de résistance: a pair of homemade multi-colored platform sneakers, crafted by gluing a half-dozen flip flops to the bottom of his Converse.

Sound familiar? Of course it does. Lecesne’s melodramatic monologue never rises above the level of stock characterizations and familiar tropes. The boys in town bullied Leonard. His aunt implored him to tone it down—even though his beauty tips proved invaluable to the ladies who frequent her hair salon. Nevertheless, he persisted, until he met the same gory fate afforded so many gay protagonists throughout the history of Western literature.

Refracted through the maudlin lens of those whose lives he touched, Leonard becomes an archetypal magical homo, doing good deeds and spreading glitter wherever he went—until the tire iron clocked the life out of him, that is. In the words of Mrs. Tochterman, whom Leonard encourages to buy a little black dress to jazz up her nonexistent social life: “He saw us. Not the way we were, but the way we hoped to be.” The dramatis personae stop short of saying he was too good for this world, but it is certainly implied.

There are elements to admire in this production, although Tony Speciale’s perfunctory direction manages to occasionally make the 70-minute running time seem endless. Lecesne’s skill in delineating the dozen characters he assumes over the course of the play comes through in an impressively physical performance; the subtle arch of a wrist or shift of an eyebrow can say more than an entire paragraph of dialogue. These effects are best matched by Matthew Richards’ haunted lighting, and complemented by Duncan Sheik’s eerie, occasionally intrusive incidental music. A handful of projections (designed by Matthew Sandagar) add some visual levity to what is otherwise a rather monotonous staging, although they sometimes evoke a cheesy PowerPoint presentation.

But in the end, we’re left with a lingering question: Do we really need another tragic story about a dead gay boy? What happened to It Gets Better? Or better yet—how about it’s just a boring gay life? At least a boring gay life is a life that gets to be lived. We don’t need THE ABSOLUTE BRIGHTNESS OF LEONARD PELKEY to tell us that the world is still hard for baby queers, particularly in the unfortunate wake of our country’s current political misfortunes. We already know it is. In the end, it just adds one more corpse to a queer body count that spans centuries.

[Suzanne Roberts Theatre, 480 S. Broad Street, Philadelphia]; May 17-June 4, 2017; philadelphiatheatrecompany.org.