Events like AT HOME WITH THE HUMORLESS BASTARD need to happen more often. It isn’t just dance; it is socially provocative artwork, with FringeArts theater a perfect venue. The heavily lit space is filled with crafty cylinders or tubes. Annie Wilson climbs into these voids in an act of exploration or escape.

Here are some more sketches from the stunning performance journey. See the first series here. [FringeArts, 140 N. Columbus Boulevard] December 1-3, 2016; fringearts.com.

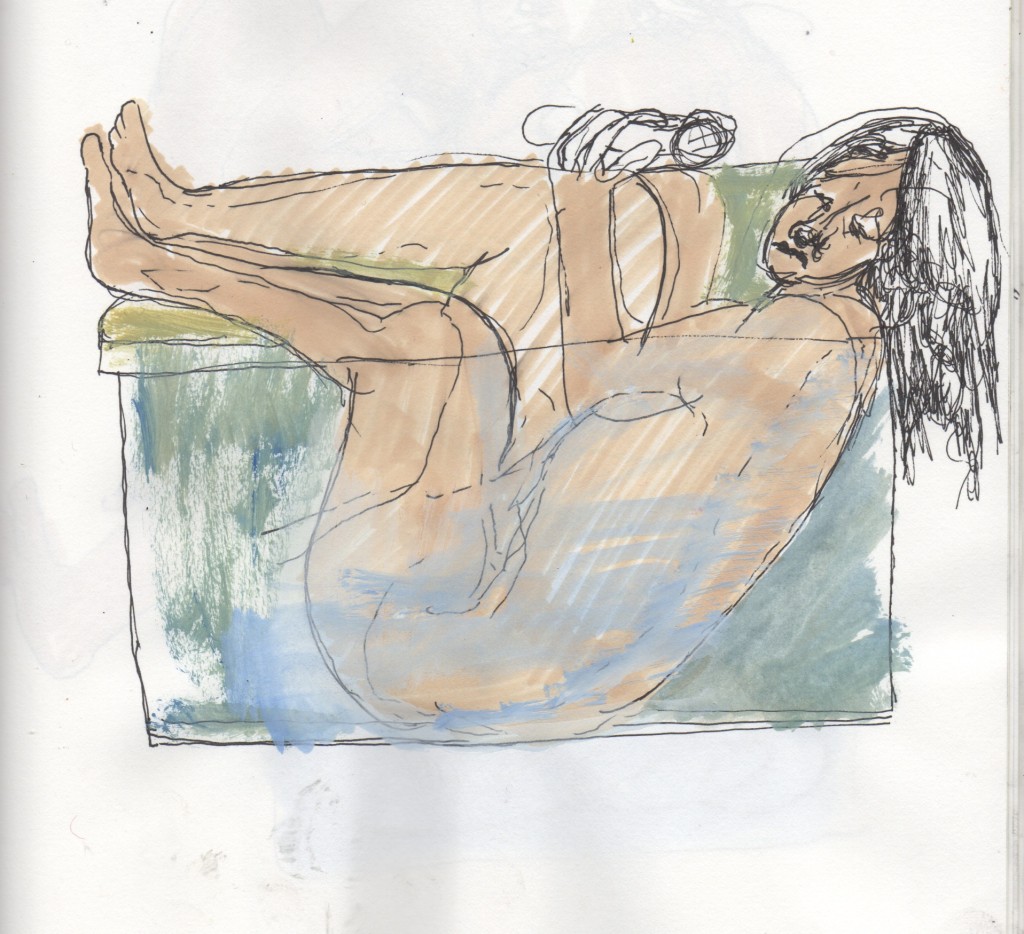

From the beginning, the stage is a vacant place and suspended above us is a plastic sheet stained with red. The singing starts and the projected voice is amplified by speaking into the cylinder. Wilson’s robe is pink, soft, and innocent.

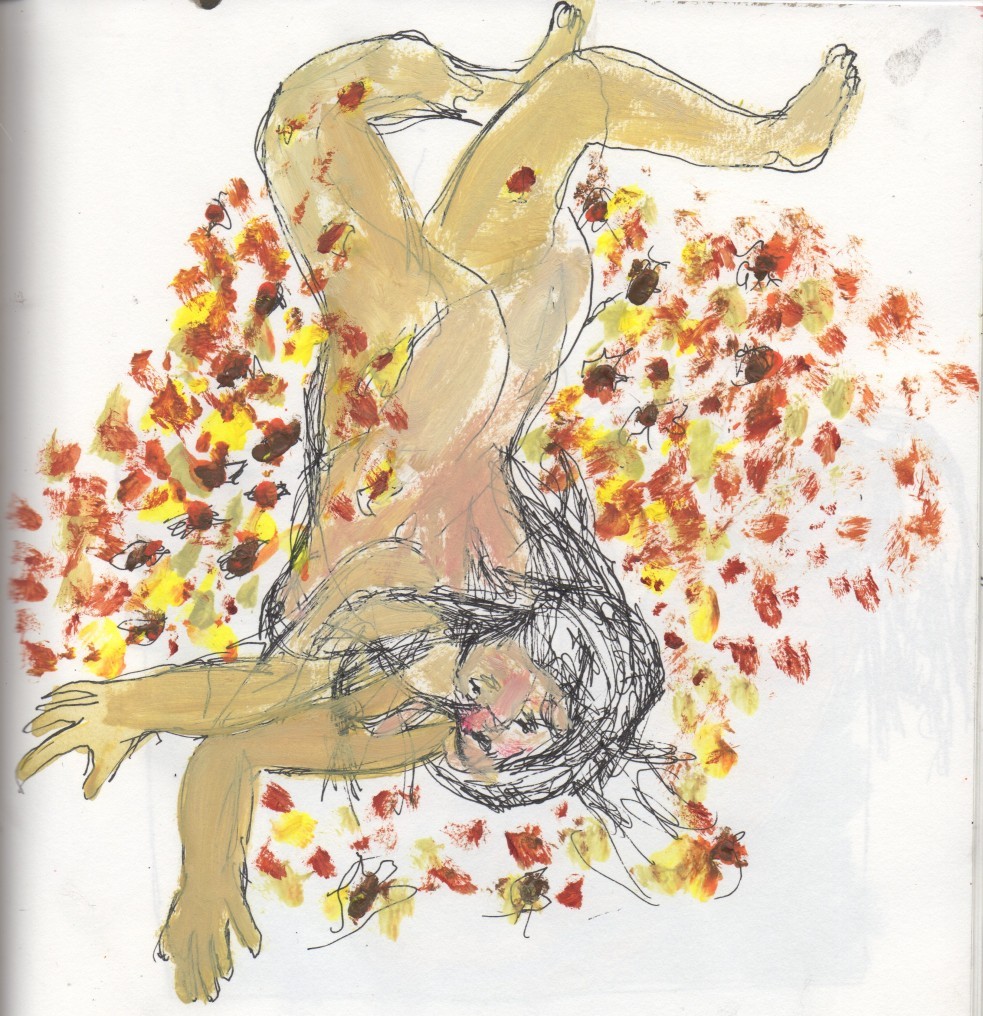

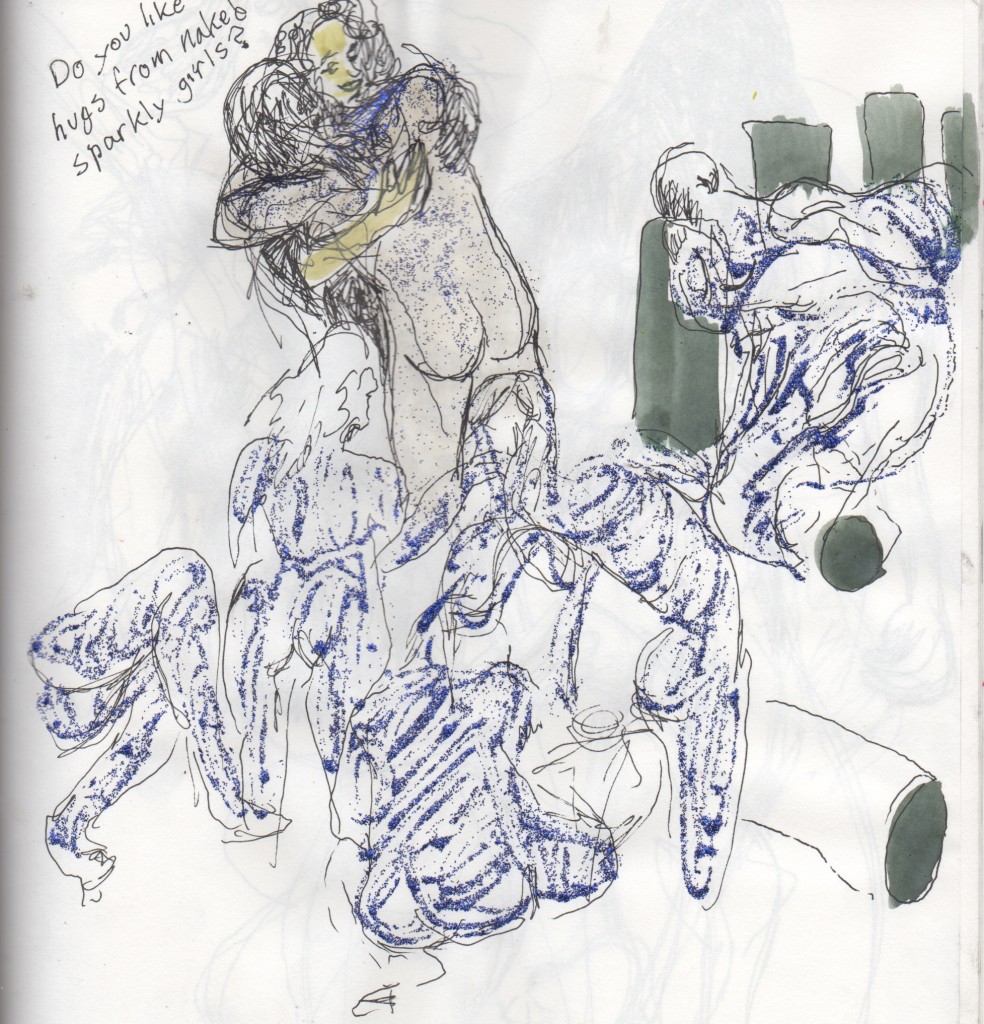

When this robe comes off the sensual voice of the body is brutally honest. Without this I don’t think Annie Wilson could have put on any costume comparable to the sparkles that she took a bath in and used to cover her body. There is a defiant act of rolling around in dirt, leaves, and other debris. It is the appearance of an animal, but the sparkles remind us of how beautiful life can be sometimes. There is nothing to hide, and there is no magic when the dance turns into a message about death and survival.

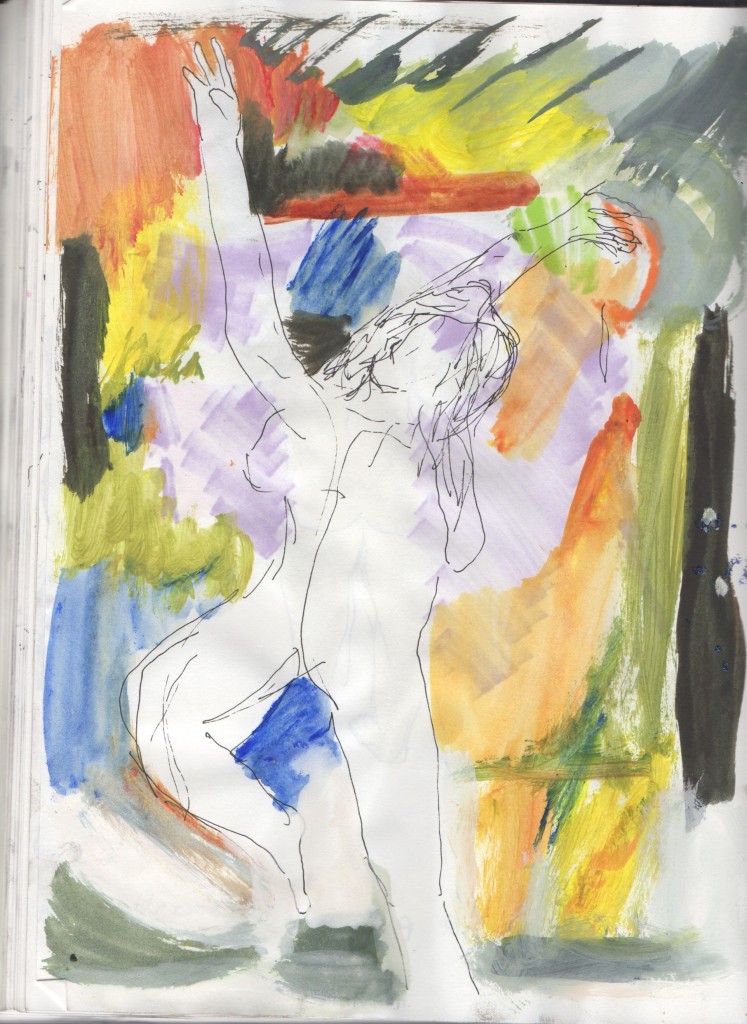

AT HOME WITH THE HUMORLESS BASTARD is a sarcastic journey through culture and sentiment. Annie Wilson loses her breath in this performance not because of the endurance but because it was a balancing act that was carefully crafted around politics and a social norm. During the times that Wilson is actually dancing we are thinking about where it is going to end up because she is taking us to a new vantage point. It is a view of freedom, but it is closer to home. We knew what we were getting into with a name like, AT HOME WITH THE HUMORLESS BASTARD, but you have to ask yourself how bastard you get. The role of the dancer in this performance is to step into the personal space. If you thought you were going merely to see a dance performance it may have been an uncomfortable yet fascinating place for you.

Annie Wilson played many voices. She stood up on one leg on a stack of pillows in a death defying pose. I was fixated on this trophy-like portion of the dance. It really stood out to me that the cushion that she stood on was there to make it unsteady like ice. The sounds of a commentator when an ice skater falls is in the background, but it’s some kind of joke the way the voice shows such compassion. The tension, the illusion, and construction of this portion of the dance highlights the darkness of the piece.

This eclectic dance is charged with African ritual and American ice skating takes precedence, but there are many moments that echo.

The African ritual is like a ceremony that partakes in spirits entering and exiting the body. It is revisiting a distant and sacred dance, we are taken aback by the unusual behavior even though we were to see a dance performance.

The African ritual is like a ceremony that partakes in spirits entering and exiting the body. It is revisiting a distant and sacred dance, we are taken aback by the unusual behavior even though we were to see a dance performance.

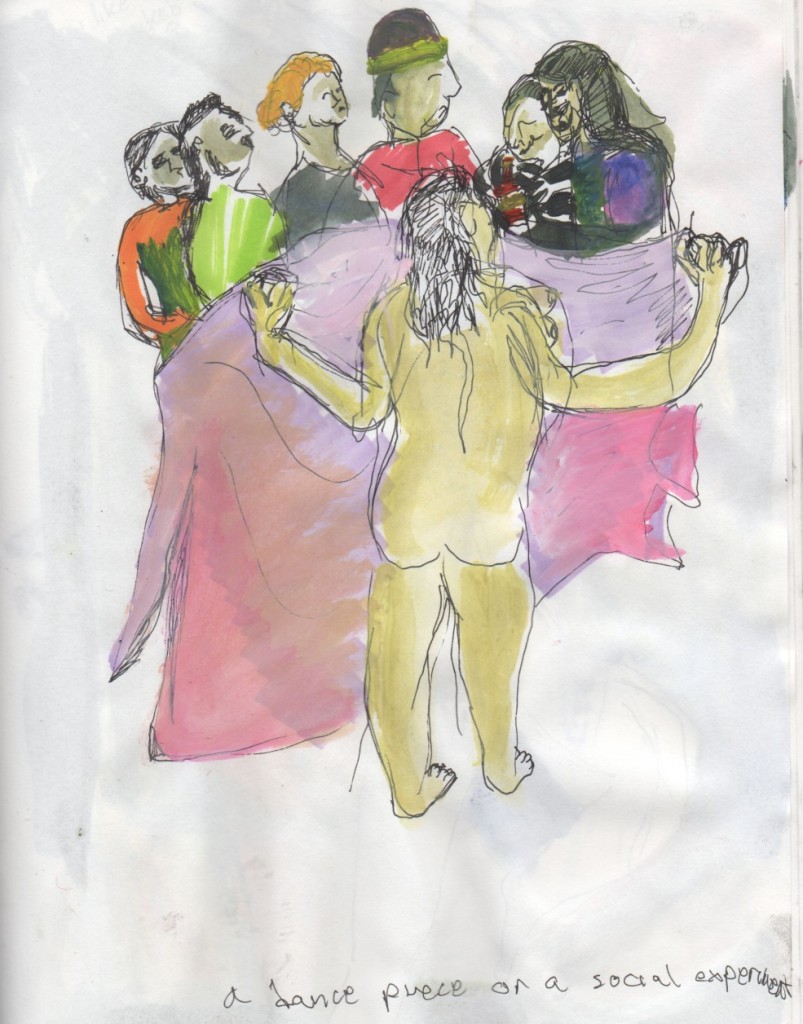

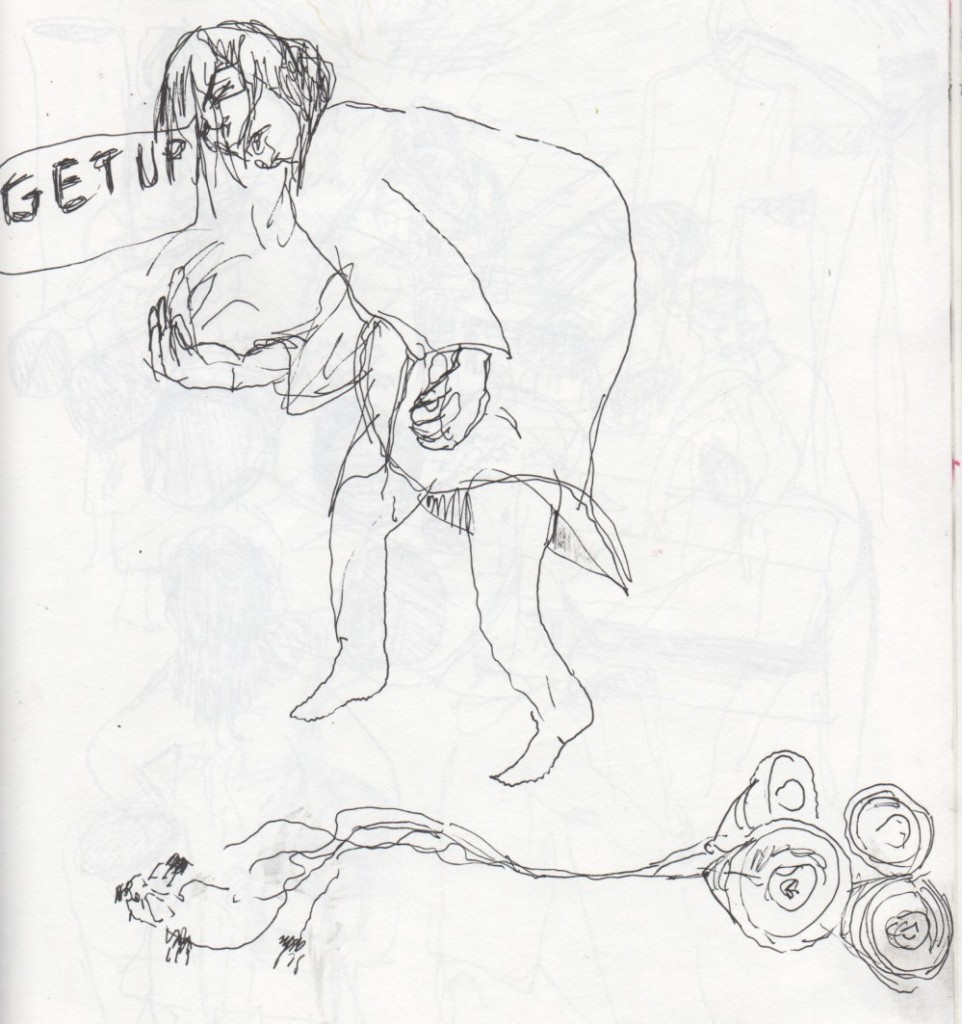

The end of the show is like a circus act, audience members are invited on stage, and the whole scenario is pretty much building us up for nothing else but to do just that. Wilson, she talks directly to the audience and makes no illusion to the lime light. When it is all done and everything is put away (at the back of the stage), the boundaries have been taken down and we are supposed to let down our walls. Wilson breaks down screaming, “GET UP, GET UP.”This is the death scene, and the headlamps and wires are not going to magically turn into anything else. The dancing takes place in-between acts, moving us from one place to another, and she swivels and sweeps in these gyrations. This is Wilson summoning up the theater gods to help lift us all up out of our seats. The dance is creating energy that she wants to share with the rest of us in the audience.

The end of the show is like a circus act, audience members are invited on stage, and the whole scenario is pretty much building us up for nothing else but to do just that. Wilson, she talks directly to the audience and makes no illusion to the lime light. When it is all done and everything is put away (at the back of the stage), the boundaries have been taken down and we are supposed to let down our walls. Wilson breaks down screaming, “GET UP, GET UP.”This is the death scene, and the headlamps and wires are not going to magically turn into anything else. The dancing takes place in-between acts, moving us from one place to another, and she swivels and sweeps in these gyrations. This is Wilson summoning up the theater gods to help lift us all up out of our seats. The dance is creating energy that she wants to share with the rest of us in the audience.

[FringeArts, 140 N. Columbus Boulevard] December 1-3, 2016; fringearts.com.