White playwrights tell the stories of black people all the time. Privileged writers often appear drawn to the stories of all varieties of underrepresented groups—not just racial minorities, but those with psychological trauma and disorder, different physical and mental abilities, variant class backgrounds, and gender identities that do not match societal expectations.

Do these writers have the understanding to take on the stories of people whose experiences diverge, often deeply, from their own? If they do not, are there others who will? Who can?

These are the questions that many in the theater community are now presenting to the public—how do we respond?

Over the past few weeks, in response to Inis Nua’s recent American premiere of The Radicalisation of Bradley Manning, eighteen theater artists in the Philadelphia area co-signed an open letter raising their concerns about the way the story of a trans woman is being played out on stage—without any clear acknowledgement of her chosen identity.

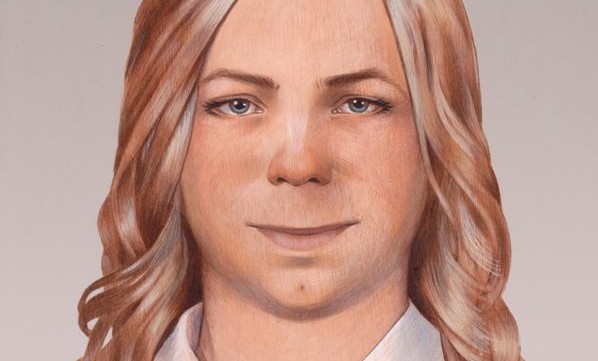

The radical play covers the semi-fictionalized history of the American soldier behind the most famous WikiLeaks. Though initially famous as Bradley Manning, this trans woman, who came out in 2013, has asked to be referred to as Chelsea.

The group wrote in their letter that the goal was “not to chastise” Inis Nua, but to “create some basic guidelines for future productions that [Inis Nua] or other theaters take on when working with trans themes.”

In response to the open letter, artistic director of Inis Nua Theatre Company, Tom Reing, held a panel discussion on Friday, May 13, 2016, to listen as people voice concerns with regard to the production, along with the way trans people are represented in the theater. Sitting on the panel were playwright MJ Kaufman and the Bearded Ladies Cabaret artistic director, John Jarboe, along with Reing himself.

The conversation began with the reason for the discussion—as listed in the open letter, concerns included issues with the use of a title and script that featured “Chelsea Manning’s given name,” and “marketing and lobby display images of her pre-transition.” It also made a note that “no trans people seem to be involved in this project,” which they deemed unacceptable in “an ensemble cast with multiple actors playing Manning.” This point was driven home using a phrase coined by the disability rights movement, “Nothing about us without us.”

Very quickly, conversation opened up to audience thoughts, concerns, and questions.

The first question came from a dramaturg who wanted to know whether or not the play should be performed at all. As Reing began voicing his opinion, the dramaturg said, “I actually wasn’t asking you.”

The director said very little for the rest of the evening.

Though the play was written prior to the public announcement that Manning would like to be referred to by the name Chelsea, playwright Kaufman stated that they felt the play should be retired, and, in the future, trans artists should be consulted when attempting to put together a piece on Manning.

Some audience members struggled with the idea that the powerful and moving play should be laid to rest due to identity politics. “When does the subject trump gender identity?” one audience member inquired.

Kaufman argued that other pieces about Manning, produced by trans artists, better represent Chelsea’s identity (for example see the Indiegogo promotion of the production Won’t Be a Ghost by the Tight Braid Group).

All in all, many people called into question the intentions of the playwright, Tim Price. Has he talked to Manning about the show? Why has he not made rewrites to reflect the identity of Manning? With Price in Wales, these questions remained unanswered.

However, Price offered up a statement, which explains his point of view (you can read it in full below). The playwright explained that he does not currently plan to rewrite the script, as the play is well-known in Britain and a rewrite would cause confusion and lead to the belief that Price had written a new play with new insights. He added, “I have been guided by my communications with Chelsea’s Welsh family, who all attended the first production and were deeply moved by the solidarity and attention we brought to her situation and campaign.”

Price sent a copy of the play to Chelsea in prison, though it appears the two have not directly communicated on the subject. However, he noted that “Neither Chelsea nor her family have raised the issue of the play title, not in the initial production nor since.”

In the end, Reing acknowledged that he should have more aggressively searched for trans actors and other theater artists to participate in the show. However, given that directors are typically not permitted to change any of the lines of a play, Reing had to decide between not showing the play at all and producing it as is. In a later conversation he explained that “Price is an important writer. If I had the money, I would have asked for rewrites, but I wanted to produce this piece because I feel strongly about Chelsea’s plight.”

The question remaining for the audience—is it worth producing the play—is troubling. Where is the line between censorship and sensitivity?

As a cis-gendered woman, it’s hard for me to say what should be done in this specific situation, and with relation to trans topics covered by cis-writers in general. I cannot offer answers to these questions, but I offer them up to the theater community at large.

The only thing I can say for a fact is that as I watched the play, I was overwhelmed by the emotion of the situation Manning was in. For me, it was not about her gender identity. It wasn’t about Chelsea Manning at all, but the atrocities she witnessed and the way she exposed the horrific truth. It was about America’s response, the world’s response, to that action.

But, I have to acknowledge there was more to the story than that. There still is. It’s a human element that cannot easily be ignored.

Tim Price’s full response:

“In 2011 when I was writing the play, Chelsea was not only incarcerated by the American military, but also in her given name, body and identity.

The desire to give Chelsea a voice, which has driven this conversation in Philadelphia, is also what drove me to write the play at the time in 2011. With the information available to me at the time, I feel I did that and am proud of the work.

As a reminder, the piece existed and was produced in 2012, eighteen months before Chelsea’s intentions were made public in August 2013. Had that information been available to me, I would absolutely have honoured her new identity.

In every piece of contemporaneous media I have made since her announcement I have been proud to use Chelsea’s chosen name and pronoun and ask all media partners to do the same. It is not difficult to get it right.

To change the title of a play I wrote five years ago and is already published in collections is a complicated decision but to have a play with someone’s name in the title that is not their chosen name also feels wrong. I don’t want people to think I’ve updated a play when I haven’t; I don’t want people to think I’ve written a new play when I haven’t; I don’t want people to come to an old play thinking this is a new play with new insights. This is a reasonably well-known play in the UK, and if productions of it started appearing with Chelsea’s name, it would lead audiences to believe that I had updated the play.

But I don’t want to cause distress to anyone, or any community, by not making a decision. It is a very unusual situation for an artist to find themselves in, with no precedent I can find.

I’ll note that, as the play has moved out into the world, and as more details about Chelsea’s life have emerged, I have been guided by my communications with Chelsea’s Welsh family, who all attended the first production and were deeply moved by the solidarity and attention we brought to her situation and campaign. A copy of the play text was sent to Chelsea as well as letters from those involved in the production. Neither Chelsea nor her family have raised the issue of the play title, not in the initial production nor since.

Chelsea has spent her whole life looking for somewhere to belong: she didn’t belong in her nuclear family, in Oklahoma or Wales, and she didn’t belong in her military, gay or activist families. It is this sense of isolation and search for belonging that fueled my interest in telling Chelsea’s story. I am deeply happy that she has finally found that sense of family and belonging in the trans community.

I’ve read Amy and M.J.’s manifesto towards justice for transgender artists which I think is a brilliant call to arms for not only the Philly community, but all theatre communities and has my total support. There are strides being made in the U.K. theatre sector with opportunities for people from ethnically diverse backgrounds, but artists who identify as disabled and trans continue to be overlooked, unless the part specifically asks for it. Colour-blind casting has made in-roads, but it is now time for gender and able-blind casting. Further, I look forward to a theater community that identifies and embraces stories written by those who have lived these experiences.

I am inspired to read and hear about the arts community in Philly taking up Chelsea’s story. Having spent years writing about Chelsea, standing on pavements and going on marches for her, it is heartwarming to hear of others on another continent caring about her. It is important as many communities as possible find their way in to Chelsea’s story, because if we are to bring about the changes that Chelsea wants to see, such as transparency, justice and oversight then we have to find common cause across diverse communities.

I feel the other concerns raised have been addressed by Tom and Inis Nua and I hope this is the start of a conversation within the community rather than an end. I appreciate the opportunity to engage in the discussion.”

As a person of several minority communities including some being represented here by Kaufman and Jarboe, and as an artist in this community, I have to say this has been an entire over-reaction by those signed to this open letter.

Kaufman has no right to silence another artist’s work and call for it to be retired. That’s not Kaufman’s space as an artist… what Kaufman’s response, as any artist to any work they don’t agree with, should be is to produce what in their mind is a better work. As artists we can disagree with anything our fellow artists put out there, but there’s no logic, no equal protection, to calling for another artist to silence themselves because you don’t agree with them. Have the argument, tell people they’re wrong, and produce something you think is better: sure! Great! It’s grand to have many voices telling a story so that at the end of the day they all sing as one and offer perspectives that we may not have seen before.