Excerpted by kind permission from SHOWMAN/SHAMAN: Benjamin Lloyd’s Ruminations about Creativity, Faith, and Culture. Edits and subheadings by Henrik Eger.

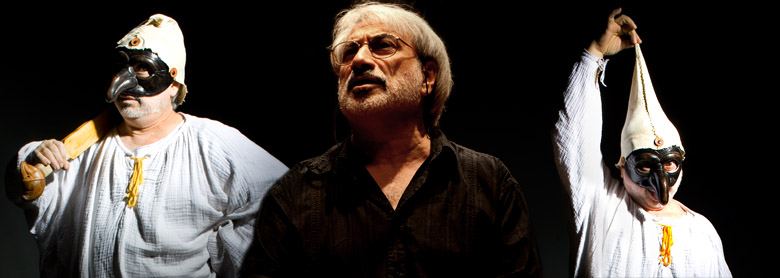

A great deal has been written about the Italian Renaissance theater and the importance of Commedia dell’Arte in modern theater history. Maestro Antonio Fava, one of the world’s most renowned experts, has spread the philosophy of the commedia and its history all over the world through performances and intensive workshops that he conducts.

Benjamin Lloyd is a graduate of the Yale School of Drama; actor and director; artistic director of Bright Invention: the White Pines Ensemble; and executive director of White Pines Productions. Together with a large number of American and international actors and directors, he has taken part in an intensive two-week workshop with Fava. Lloyd wrote an extensive report about his experience in 2006, “Master Class with Antonio Fava.” Below, excerpts from this fascinating report in two parts: 1. Commedia dell’Arte, its history and goals; 2. Experiencing the famous Antonio Fava in action, teaching at the Ethical Society in Philadelphia.

Commedia invented the modern theater

Antonio Fava posited that commedia invented the modern theater: it was the first to charge a fee to see a play, the first to form companies of artists, the first to create guilds or unions to represent theater professionals. “Commedia’s first idea,” said Fava, “was that theater is a product and it’s possible to sell it.” Fava said that it was the first type of theater to employ actresses. “There are no stars in commedia dell’Arte!” He also stressed its deep appreciation for the populace. “We have a mania for the audience . . . Commedia must be spectacular. Laughter cleans out the suffering of the people.”

Commedia is slighted because it lacks a lot of written texts

From the beginning, Antonio Fava hammered home the point that commedia is theater like any other form of theater. You pay for a ticket, you sit in your seat, the curtain opens, you watch the play. His insistence on this seemed borne of a frustration that many regard commedia as something other than “real” theater. More than once he made fun of “intellectuals” who lifted their noses at his beloved art. Fava insists that commedia is slighted because it lacks a lot of written texts that can be studied. As such, it is not suited for the academy.

Fava teaching Commedia dell’Arte and audience involvement

Commedia is unforgiving in pace and self-indulgence. Commedia is multi-tasking on steroids. Dottore is one of the characters that brings direct audience interaction into play. Fava said it’s okay to involve the audience this way, but you must never have an actual conversation, or ask a real question, it is always rhetorical, so the actor remains in control and the audience feels safe.

Things to avoid in Commedia dell’Arte

He told us to avoid anything which might offend anyone in the audience, such as references to actual religions or politicians (he was contemptuous of some political commedia he saw once). Obscenity and poo-poo humor, however, has a glorious role to play in commedia. But Fava made sure we understood that when something was obscene in commedia, it was obscene by accident. “The audience sees it as obscene, not the characters involved.” Obscenity is not to be confused with lust, appetite, and desire, which are frequent engines driving plots and characters. But in a typically European fashion, Fava did not regard anything about these drives as obscene, only human. How enlightened.

Studying with Maestro Fava, “The most intensive training I have had since drama school”

The two weeks I spent with him and the others were the most intensive training I have had since drama school, some 20 years ago. It was exhausting, and I was frequently dripping with sweat by the end of the first hour. Blanka [Zizka] turned to me on the first day, as we were making spastic fools of ourselves, trying to get the hang of the grand zanni walk and said, “It’s terrifying. But I love it.”

Performing daily from the very first class

Fava would begin by spending an hour and a half instructing the entire group in a particular character, their postures and movements. He was exacting and precise. Then he would have the whole group doing exercises in this character. This first hour and a half tended to taste of the asylum a bit. Then a break. Then another hour and a half in which he usually talked smaller groups through demos, which they would then perform as we all watched. He never asked anyone up. He would say something like, “Two or three, please” and those feeling brave and crazy would get up. We gradually learned we each would be seen. So right away we were performing—from the very first class.

Then lunch for an hour. Then more small groups. Then he would assign the canovacci [skits employing authentic Renaissance theater archetypes learned that day]. We would have an hour to rehearse something to show, then guests were invited in and we would perform these large and frequently unwieldy scenarios.

Fava’s response to his students

I do remember him saying, “I will teach you correctly, and you will make mistakes. This is okay; it is the only way to learn.” Fava’s response to our work was always loud, lusty, and genuine. He was amused by our choices, even when they were bizarre, and fascinated by our mistakes. He managed to create an extraordinarily supportive environment in a room full of self-conscious theater people making fools of themselves—over and over. This is no small feat.

Many of us were unable to simultaneously perform what we had rehearsed AND physically represent the character we were playing. This was us learning by our mistakes, with Fava roaring from a chair in the middle of the impromptu audience.

When we failed, we were never reprimanded, only encouraged to try again

And he taught us the great virtue of forgiveness, for when we failed, we were never reprimanded, only encouraged to try again. This is a gift to be held close to one’s heart.

Fava accomplished something great

Fava accomplished something great: the teaching both of things tangible—like the precise physical requirements of each character—and of things intangible, like the great love one must have for all humanity to bring these strange and magnificent people to life, and the courage required to do them justice on stage.

Antonio Fava, world renowned Commedia dell’Arte expert, master classes in Philadelphia, sponsored by the International Opera Theatre at the Ethical Society of Philadelphia, February 8-12, 2016, followed by special visits to universities and theaters in the greater Philadelphia area, February 15-19, 2016. Contact Karen Saillant at karen@internationaloperatheater.org for further information.