A teaching professor at Drexel University, Gerry Hooper is a director, editor, and director of photography for narrative and documentary film, with work ranging from independent features and Bollywood cinema to documentaries for broadcast. His research focuses on new international cinema, especially evolving forms of narrative and documentary styles, and evolving media technologies and their impact on creative approaches to filmmaking. He is working on two documentaries and a narrative feature film.

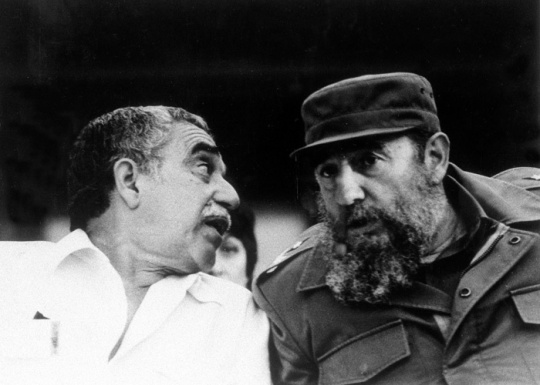

Hooper is taking a class of ten Drexel film students to Cuba where they will spend two weeks (December 6-21) studying and shooting documentaries at the legendary Escuela International de Cine y Television (EICTV) in San Antonio de Los Baños—one of the most important audiovisual training institutions in the world, which implements the teaching philosophy of “learning by doing” with teachers who are active filmmakers. It was founded in 1986 by Nobel Prize laureate Colombian novelist, short-story writer, and screenwriter Gabriel Garcia Marquez; Argentinean poet and filmmaker Fernando Birri; and Cuban theoretician and filmmaker Julio Garcia Espinosa, amongst others, and is supported by the government of the Republic of Cuba.

Originally conceived for students from Latin America, Africa, and Asia, EICTV now accepts students in the audiovisual field worldwide. Thousands of professionals and students from over 50 countries have passed EICTV, which has become an important center for cultural diversity. Drexel’s Antoinette Westphal College of Media Arts & Design already has study-abroad programs established in London, Tokyo, Rome and Sao Paolo. Thanks to the recent warming of relations between the US and Cuba, Drexel’s film program is one of the first partnerships between the famous Cuban film institute and an American university.

Henrik Eger: Tell us how your interest in international cinema took you to consider doing something that was impossible for most Americans for decades, namely planning an educational trip to Cuba.

Gerry Hooper: I have met Cuban filmmakers through a seminar. I also know a Columbian film scholar who had personal connections to EICTV, the film school in Cuba that we are running the workshop with. The time was right since educational trips are now permitted in the thawing political relationship between the two countries.

Eger: Given the many years of a cultural blockade of Cuba by the US, how easy or difficult was it to get permission from Drexel, the US Department of State, the Cuban government, and the film institute to take US students to Cuba on a film project this December?

Hooper: Not too difficult, really—just a good bit of organization that is involved in doing something so new and organizing the realities within the formal structure of both schools. Because it is the first time and the legal frameworks between the countries are changing, it requires proceeding more cautiously and making sure that everything is properly cleared. The Department of State only insists at this point that you file an affidavit ascertaining the reasons for your trip within the categories that are permitted. Because of the lack of a formal banking relationship, there are some complications with financial exchanges—but nothing too formidable.

Eger: What was the response at Drexel to your plan to take your students to Cuba?

Hooper: Colleagues and university officials—simply put, it was overwhelmingly positive, enthusiastic, and supportive on every level.

Eger: What did you do to prepare US students for this cultural journey to a country that, for decades, has been portrayed as part of the “evil empire” by many US politicians, just as the same rejection in reverse was fostered by Fidel Castro for years?

Hooper: Some students that are participating do know Spanish, and I think in general, students are aware of how false political hyperbole can be as opposed to the reality on the ground. Students were very enthusiastic about going and they have met with me and our study abroad department to get a better sense of what the Cuban reality is. While [in Havana], they will be working with bi-lingual film crews and faculty from EICTV. This [cooperation] will facilitate greatly their ability to shoot in Havana.

Eger: What is your goal teaching film in Cuba, something that you could not do in the US?

Hooper: The goal is to give the students an opportunity to both experience the richness of a culture with which they are unfamiliar, to broaden their base of knowledge of filmmaking and national narratives, to give them the opportunity to learn more about themselves by living and working, although briefly, in a foreign culture, and to afford an opportunity that will come close to what they may experience professionally as documentary filmmakers as they pursue their careers.

Eger: What kind of stories or documentaries to be filmed in Cuba have your students proposed so far?

Hooper: The students will only propose their ideas after spending a week on the ground, so nothing is being pre-determined at this point. The film projects will be determined after the students spend time in Old Havana, investigating as best as possible people and stories they find there and then voting on about three films to be made.

Eger: That almost sounds like a Survivor episode for creative American filmmakers in Cuba. How are you and your students going to structure this huge project?

Hooper: Students will probably work in groups of three during production, handling research, interviews, B-roll footage [supplemental or alternative footage that can be intercut with the main shot], and other aspects of the actual shooting.

During the second week, following shooting during the day, the students will review footage at night and begin to organize it, add subtitles, etc. They will handle post-production [editing picture and sound] as a team, with different responsibilities divided up during [the] initial editing period at night while in Cuba. This could include organizing and quality control of the footage we shot during the day.

Footage won’t be uploaded to the web as the Internet is very limited in Cuba. Back at Drexel, the projects will be fine cut. The students will share direction—one might search for archival footage, one might handle sound editing, etc. When the films are done, copies will be sent back to EICTV.

Eger: Will you and your students visit Hemingway’s home in San Francisco de Paula, a small suburb of Havana, and perhaps film there as well?

Hooper: I doubt it as they will be very busy. They do have credentials to attend screenings of The Havana International Film Festival, which is running concurrently while they are there. It is also taking place in the neighborhood in which they are staying. This is a significant international festival and I suspect the students will attend as much as their time allows.

Eger: You will probably get questions from Cubans as to why filmmakers in Cuba, whose films are shown all over the world, are not being invited to film and teach in the US. What would you say? Or has Drexel made plans to invite Cuban filmmakers and their students to film at Drexel?

Hooper: This is the beginning of what we hope will be a continuing relationship with EICTV and hope that it will develop further as EICTV is one of the pre-eminent film schools for Latin America. I think Cuban filmmakers understand very well the political realities that have resulted from governmental policies. They distinguish, I think, between the Americans they meet and the American government.

Eger: Your students will complete the films during the winter term and they will be screened at Drexel in the spring. Have you planned a Cuban-American film festival to strengthen the cultural bridge between both countries?

Hooper: No, as of now the only plan is for a screening of the films that they complete.

Eger: Is there anything else you would like to share?

Hooper: [This joint film project in Cuba] is a terrific opportunity for the students and the university.

Eger: Muchas gracias y viva Cuba, viva Estados Unidos, y viva cooperación.