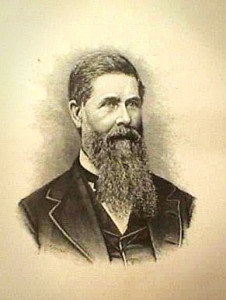

Few people were as important to the history of mid-to-late-nineteenth century United States as Philadelphia financier Jay Cooke (1821–1905). Using the same tools and savvy marketing that built railroads across the Eastern seaboard and into the West, his Philadelphia banking house raised as much as a billion dollars for Union war efforts over the course of the Civil War. His speculation on the Northern Pacific railroad after the war helped open much of the American northwest to white settlement, but ultimately led to the financial panic of 1873, which plunged the country into a deep recession.

Throughout this period, Cooke and his banking house were intricately involved in national and regional politics, corresponding with and influencing government employees all the way to the president. His correspondence and personal papers, held in the archives of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, thus provide a unique view into the political and financial workings of mid-nineteenth century United States.

Cooke was born in the rural town of Sandusky, Ohio. His father, Eleutheros Cooke, was a prominent lawyer and briefly a U.S. Congressman. (Eleutheros was named after an obscure second-century Christian saint; disliking his own moniker, he chose as short and simple a name for Jay as possible.) An ancestor, Henry Cooke, arrived in Salem, Massachusetts, as early as 1638, and both Jay’s grandfathers fought in the Revolutionary War.

In 1838, while still in his teens, Jay got a job in Philadelphia with his brother-in-law as the bookkeeper and general assistant for a Philadelphia to Pittsburgh transportation company. The enterprise soon folded, but not before Cooke had attracted the attention of banker Enoch W. Clark, who offered him a clerk’s position at his small banking house. By 1843, Cooke had risen to become a full partner; when Clark died in 1856, Cooke took over the bank’s operations.

As Cooke built a small fortune for himself and the bank, purchasing and selling land and dealing in railroad bonds, his brothers were making key contacts in DC and elsewhere. Pitt Cooke wrote frequently to Jay as he built a web of business relationships throughout many states. Journalist Henry Cooke sent insider reports from the nation’s capital and built a friendship with Ohio Senator Salmon P. Chase that would prove invaluable when Chase was appointed Treasury Secretary in 1861.

Jay Cooke “retired” from banking in 1858, but continued to put high-stakes deals together. He fully reentered the banking world in early 1861, launching Jay Cooke & Co. with his brothers and brother-in-law, railroad magnate William Moorhead. A full supporter of the North in the Civil War and longtime opponent of slavery, Cooke soon became involved in financing the Union efforts. On April 13, 1861, as Fort Sumter was being bombarded by Rebels in South Carolina, Pitt wrote to Jay to congratulate him for success in the “bid for the $200,000 treasury notes.”

“I was delighted,” Pitt enthuses. “It was patriotic and I trust it will be profitable. Our Government now they have commenced the war at Charlestown must be sustained at all Hazards. There is no half way about it.”

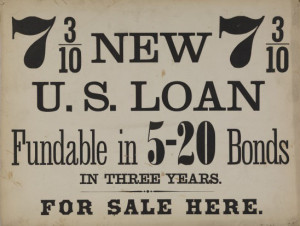

Jay Cooke proved himself an immensely successful promoter of the Union cause, and his patriotism reaped great profits. His success in selling state bonds and federal bonds in Pennsylvania led Secretary Chase to appoint Cooke a “Subscription Agent for National Loan” in September 1861 and sole agent in May 1862, praising his “high character and known devotion to the public welfare.” Cooke’s bank acted in the national interest in other ways, secretly selling government gold and bonds to secure price stability.

Cooke was a patriotic believer in the Northern war, and his imaginative use of advertising and sales agents tapped into the national mood as no other banker could. But in raising perhaps $1.6 billion for the country (fully one-fourth the total U.S. war expenditure), he also amassed a sizable fortune for himself and his bank, through direct commission and access to valuable insider information.

In the months after the war, Cooke built a million-dollar mansion on 200 acres to the northwest of Philadelphia, in the area now known as Elkins Park. Named “Ogontz” after an Indian chief Cooke knew as a child, the estate included huge parks, gardens, and mock ruins, with a fifty-three-room house chock-full of expensive paintings, sculpture, and furniture. Near his childhood home in Ohio, Cooke bought an eight-acre island in Lake Erie named Gibraltar, and built a 15-room house and observation tower of the same name as his primary vacation house. His papers contain many references to and pictures of both houses.

Despite his vast new wealth, Cooke retained some strong ethical commitments, quickly backing out of a dubious wartime deal for Southern cotton when he realized its implications. Famously, he and his partners extracted their profits from Jay Cooke & Co only after a ten percent tithe had gone to charitable and religious causes. He was proud to use Gibraltar as a getaway place for dozens of Ohio and Pennsylvania clergymen. Among his letters are many requests for charitable donations and notes of appreciation for gifts given and for hospitality on the island.

Cooke’s fortunes only increased in the years following the Civil War. He remained a trusted dealer in government bonds and in bonds for the ever-growing network of rail lines across the United States. His bank also invested in mining concerns and in the new business of oil drilling, which grew in strides after the first oil well opened in Titusville, Pennsylvania, in 1859. But Cooke shied away from what he termed “speculation,” usually preferring to invest in railroads to serve existing oil fields rather than risky new wells.

Cooke’s fortunes only increased in the years following the Civil War. He remained a trusted dealer in government bonds and in bonds for the ever-growing network of rail lines across the United States. His bank also invested in mining concerns and in the new business of oil drilling, which grew in strides after the first oil well opened in Titusville, Pennsylvania, in 1859. But Cooke shied away from what he termed “speculation,” usually preferring to invest in railroads to serve existing oil fields rather than risky new wells.

His risk-averse nature also stopped him from getting involved in the second great transcontinental railroad, the Northern Pacific, when offered the chance in 1866, writing to his brother Henry:

“[W]hat Wm. G. [Moorhead] & myself fear is becoming identified with any of these great projects, in such a way as to inevitably draw us into advances. Our true future is to keep out of large entanglements & to undertake nothing or be connected with nothing that will require any advances. We will always have plenty of opportunities to negotiate after concerns are fully organized and plenty of opportunities to use our money and our time; so don’t let us get into any of these entanglements except those that grow out of our connection with the govt.” Cooke’s hesitation was to prove prescient; his reluctance to become entangled regrettably short-lived.

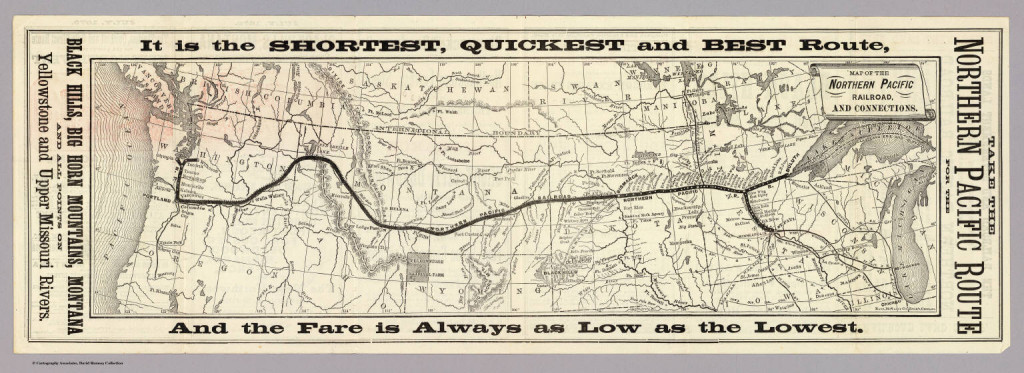

Intended to connect Washington and Oregon with the Great Lakes and to open up the Northwest territories for settlement, the Northern Pacific was established by Congress in 1864, not long after construction started on the first transcontinental line, the Central Pacific. But by the time that line was ceremoniously completed at Promontory Summit, Utah, in 1869, construction still had not begun on the Northern Pacific.

Perhaps impressed by the ease with which Jay Cooke & Company had sold $4.5 million in bonds for the Lake Superior & Mississippi Railroad in eastern Minnesota, in 1870 Cooke forgot his earlier unease and contacted the Northern Pacific board about organizing a huge fundraising effort. He was quickly able to raise $5.5 million in bonds, but secured no major investments from other banks or railroad companies and failed to get Congressional support for cash subsidies or bond guarantees. In 1871, Cooke launched a heavily advertised public bond sale, raising $13.5 million.

But despite this influx of cash, construction on the railroad was slow and rife with difficulty. The terrain proved tougher than expected; and the tensions with the Sioux Indians (which would culminate in General Custer’s devastating defeat at Little Bighorn in 1876) prevented work along much of the route. Cooke’s letters show a close regard for the day to day work of the project, with frequent back and forth communication regarding materials, engineering, and other aspects of construction.

To ensure progress and guarantee a return of investment, Jay Cooke & Company was forced to pour increasing amounts of its own money into the Northern Pacific. Cooke’s partners became progressively worried at the exposure of the bank. In September 1872, Harris C. Fahnestock, who owned 14% of the bank, warned Cooke “Under no consideration must you allow your pride or interest in the company to place us in a position of even possible complications with its troubles.” By that December he was describing their situation as “perfectly helpless”.

By September 1873, the Northern Pacific was facing bankruptcy and Jay Cooke & Company had gone deeply in debt to cover its mounting losses. A money crisis in Europe made it increasingly difficult to raise capital. Cooke lobbied hard to secure a large government loan and prepared to promote another huge bond sale, but the situation proved increasingly dire. On September 18, 1873, Fahnestock ordered the New York office of the bank to literally close its doors, signalling its inability to meet its liabilities. The failure of the bank sent shock waves through Wall Street and American financial markets, kicking off the Panic of 1873 and ushering in a downturn that would last for six years.

Cooke filed for bankruptcy, both for the bank and personally. He was able to pay off his creditors and rebuild a portion of his fortune thanks to investments in a Utah gold mine, enabling him to repurchase his beloved Gibraltar estate and turn Ogontz into school grounds for the Chestnut Hill Seminary. (This school became known as Ogontz college, which in a new location became the Abington campus of Penn State University.) Later in life, Cooke completed a journey on the Northern Pacific railroad, which was finally completed in 1883. He died in 1905 and was buried in Elkins Park.

Previously published by Pennsylvania Legacies

7 Replies to “Jay Cooke: The Philadelphia banker who funded the Civil War, caused one of the nation’s biggest financial collapses, and founded Penn State Abington”