While perusing the pop culture section of Bill Simmons’ Grantland site a couple weeks ago, I came across a piece by contributor Sean Fennessy detailing an interesting event that took place at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) late last month. The event was hosted by Film Independent—the non-profit organization behind the Independent Spirit Awards and the Los Angeles Film Festival—as part of the Film Independent at LACMA Film Series. The FI@LACMAFS is described by LACMA’s website as an “inclusive series offer[ing] unique film experiences, bringing together Film Independent’s large community of filmmakers and wide spectrum of audiences with LACMA’s commitment to presenting cinema in an artistic and historical context.”

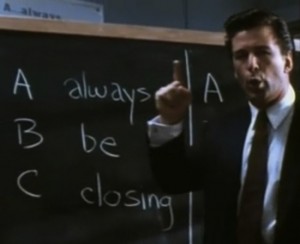

The event in question was a reading—or, per the website, a “Live Read”—of David Mamet’s film adaptation of his own play, Glengarry Glen Ross. Well known to theater geeks and fans of “HOO-AH!“-era Al Pacino, Glengarry tells the story of a group of sketchy, miserable, fifty-something timeshare salesmen who scheme among themselves to steal the hot new sales leads being held captive by their tyrannical bosses (there was an episode of The Office kind of like this). The play won Mamet the Pulitzer Prize in 1984 and the 1992 film—starring the dream cast of Pacino, Jack Lemmon, Ed Harris, Alec Baldwin, Kevin Spacey, and Alan Arkin–remains the best and most popular Mamet adaptation on celluloid.

The Live Read at FI@LACMAFS–brainfathered by FI@LACMAFS curator and esteemed film critic Elvis Mitchell—put a curious new spin on Mamet’s classic story: all of the roles—written specifically for men—were read by female actors.

This is not unusual. One of the hallmarks of postmodernism is an interest in reinterpreting super-famous works through the eyes of cultural groups not necessarily considered by the original authors. Gender-swapping, racial substitution, placing old works in modern settings—these have become common methods of interpretation in contemporary theater and film. But there are two questions I have about the Glengarry reading that Fennessy unfortunately does not address in his piece.

The first is: What, if anything, is gender-swapping supposed to do for the story or for the audience? The second is: What does David Mamet, Glengarry‘s author and a notorious theater traditionalist, have to say about this?

Fennessy quotes curator Mitchell’s introduction to the Live Read: “[Mamet’s] characters are hard-hearted and hardheaded,” he says, “so I thought Women can do that.” All well and good. And to Mitchell’s credit, he got some amazingly talented actresses—Catherine O’Hara, Maria Bello, and Robin Wright among them—to read Mamet’s jittery script. But what goes undocumented by Fennessy—it is hinted at but never explicitly stated—is whether Mitchell was trying to make some kind of statement with his new take on the script, or whether the casting was simply a fun gimmick for a one-night reading at a festival with way too long of an acronym.

Glengarry Glen Ross is a superior play with six killer roles–roles which, in a traditional production, would all be played by men. Juxtapose this against the fact that every actor has dream roles; every actor craves those famous, complex roles written by the greatest writers in history. And we don’t get to play some of those parts, because some of those parts are written for the wrong gender.

So for a group of talented female actors to get together and have a whack at Mamet’s male-dominated script is great fun; just as it would be great fun for me to get up and play Martha in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? And if I did so in an informal setting, just for shits, with some talented friends, I think it could be totally cool. But what would you think if I—a twenty-six year old man–were cast as Martha in a main stage production at a respected theater, charging $35-$50 per ticket, playing opposite a woman cast as George? Would that be an effective rendering of Edward Albee’s play? Would it even be Albee’s play anymore? What does purposeful miscasting, or any such gimmickry, really do for theater?

I’m not really bothered by the GlenGarry Live Read. I’m not bothered because it was a one-night special event, done (I assume) just for shits, rather than a full-fledged production by an established company. But the practice of repurposing classic works in this manner—often to suit the artistic aims of a specific director or company–is far too common in legitimate stage productions (and films, for that matter) and serves only to distort the aims of great playwrights and inflate the egos of pretentious artists arrogant enough to think that they can improve on established works by changing their content (and thus, their intentions).

Last spring, I accepted a gig as an assistant stage manager for a well-known play by a well-known playwright at a theater that, in the interest of good taste, shall not be named. While my training is mostly in acting, I started stage managing a few years ago in the interest of getting more work and making connections. Those connections got me the aforementioned gig, and probably would have yielded more gigs (and better-paying ones) if I’d stuck with it. But participating in this production, and witnessing the ludicrous artistic decisions being made—decisions which I, as a non-artistic participant, could not rightly argue—is what finally convinced me that I could never, ever be a non-artistic theater professional.

(I should note that this is in no way meant to belittle the work of theater technicians. I learned a great deal from stage managing and worked on some fine productions. This is simply to say that, for me, the way to personal satisfaction with my work was not, as it turned out, down this avenue.)

The director of this play added slapstick gags, musical numbers, a tricked-out set and a fifteen-minute pre-curtain pantomime routine to our production of the play. None of these elements were in the script; all of them distracted from the story being told. I became inflamed with righteous indignation each day as the play was added to and added to, with no consideration for the intentions of the playwright (or for common sense). I kept a pocket-sized notebook of every incident–every idiotic direction, every twenty-minute mandatory yoga warm-up, every unhelpful addition to the action. By the time the play opened, my notebook was full.

The genders weren’t switched, nor was the time period changed; but the effect of the additions—what the director called “experiments” or “playing with the script”—was to mangle the story and, insultingly, for the play to bear the mark of the director more than that of the playwright.

Now we can talk all day about the job of the director as interpreter of the script, but what kept coming to my mind during this production was the following fundamental question: If you wish for your production of the play to communicate something other than what the playwright intended, then why are you doing the play?

While working on this production, another company announced auditions for what was to be an all-male production of Shakespeare’s Othello. This was a gimmick that made sense—kind of. Those familiar with a certain well-known Gwyneth Paltrow movie will remember that, during Shakespeare’s time, women were not allowed on the stage. As such, if you went to the Rose or the Globe or the Curtain in 1604 you’d see young boys playing Desdemona and Emilia and Bianca and all the Bard’s other great female roles. So maybe this company was striving for some kind of authenticity in their production that isn’t achieved very often now that women are allowed to perform. I mean, right?

Thing is, if Shakespeare could have had women playing Desdemona and Emilia and Bianca then he would have cast women in those roles. But if Shakespeare wanted his plays to be staged—that is, if he wanted to make a living and earn his daily bread and not get thrown in jail–he had to adhere to the laws of an oppressive government. Theaters were not making some kind of “statement” by casting only men in their productions; they were simply playing by the rules. They had no other choice. Now that we do have a choice—now that we can stage Shakespeare’s plays the way he would have wanted them performed—why would we go back and do it the old, repressive way? Unless, of course, it’s just for shits?

When directors bend the rules set down by the playwright—when they cast men in female roles and change Venice to New York and arbitrarily add musical numbers—they often defend it by calling it their “take” on a classic. What they’re really saying is, “I wish this play said something other than it does, so I’m going to change it so that it says what I want it to.”

Then why, oh why are you doing the play?

Or maybe the better question is: If you don’t like what the play is saying—if there is some specific theme or message that you want to convey to your audience that is not found in the text of they play at hand—then why don’t you write your own damn play?

More often than not, the kind of gimmickry discussed in this piece is little more than the mark of the director as wannabe playwright.

When I brought up the Glengarry reading to a friend, he directed my attention to a particularly nutty production of Samuel Beckett’s Endgame that just finished an extended run at a well-known Philadelphia theater company. (Reviewed here by Phindie)

Samuel Beckett wrote dry, dreary plays about the hopeless plight of humans in a godless, ignorant universe. His characters are often one-dimensional metaphors for suffering who trudge through their misery with repetition, rituals, and darkly vaudevillian comedy. In addition to being a profoundly morose human being, Beckett was intensely protective of his work, insisting that any and all reproductions of his plays adhere strictly to his stage directions and do not add elements to the staging. While he never spoke much about his work when pressed for explanations or analyses, he was wont to publicly denounce and even refuse performance rights to any production of his work that did not follow his rules. After his death in 1989, his estate handled these matters in a similar fashion, or so I thought.

The production of the 1957 play Endgame that just ended its run in that well-known city on the Delaware reportedly took serious liberties with Beckett’s text. Before I go into detail, here’s a quote from the playwright, cited in a glowing review of this same production from Stage Magazine:

“Any production of Endgame which ignores my stage directions is completely unacceptable to me. . . . a complete parody of the play as conceived by me. Anybody who cares for the work couldn’t fail to be disgusted by this.”

Have you got it? Now, consider the fact that Beckett’s stage directions are (by contemporary standards) incredibly explicit; in addition to describing the action to be taken by the actors, his directions also tell you what the set should look like, what the characters should look like, what they are wearing and when they should yawn. The stage direction regarding the set for Endgame in particular is as follows:

Bare interior.

Grey Light.

Left and right back, high up, two small windows, curtains drawn.

Front right, a door. Hanging near door, its face to wall, a picture.

Front left, touching each other, covered with an old sheet, two ashbins.

To contrast, here’s a description from that Stage Magazine piece of the set for the Arden’s recent Endgame:

“…an expansive post-industrial space in an abandoned subway station . . . below a partially collapsed overpass, draped with fabric and detritus—a crashed car, a fallen electronic schedule board, and cracked concrete. A damaged louvered air vent and a hole in the roadbed above substitute for Beckett’s windows and allow Clov a peek at the world outside.”

So….yeah.

I’m not saying this rendering of Beckett’s bleak wasteland as a post-apocalyptic metropolis isn’t creative. It’s certainly creative; it’s inventive and clever and gives you an insight into how the director sees Beckett’s masterpiece in his head. But there are two very big problems with this: First–and this is especially important for me as a Beckett fanatic but should be important to any fan of good, unpretentious theater—if I’m going to see Endgame, I want to see the play Samuel Beckett wrote, not the play some director wishes Beckett would have written. Secondly, when we toy with classic works in this way, the only members of the audience who will be able to judge the aptitude of the director’s interpretation are those who have already read the play. Anyone unfamiliar with Endgame—and while the play is well-known in theater circles I’m willing to believe this demographic accounts for at least 51% of this particular theater’s audience, probably more—will come away thinking that this blasphemous production represents what Samuel Beckett is all about. I can’t imagine a worse introduction to a truly great artist.

If you are sympathetic to this open-interpretation method of artistic direction, you may be thinking that I’m being somewhat unfair to this production, especially since I clearly did not see it. Maybe you’re thinking that my mind could be changed by seeing Endgame performed in this manner, or at least that I shouldn’t be so harsh on something I haven’t actually experienced. Maybe you think I’m being a bit of a theater fascist and need to be open-minded about the interpretive desires of certain directors. I see where you’re coming from, but you are wrong.

One of the first works I read by Samuel Beckett was his 1938 novel, Murphy—a book about a character desperately trying to escape his own narrative. In addition to being a thoroughly wacky tale and an early example of what would become absurdism, Murphy exemplifies Beckett’s frustration with the lack of restraints put upon the author of a novel. In an interview in Mel Gussow’s outstanding collection, Conversations With and About Samuel Beckett, Beckett describes his need for boundaries in his writing. To him, novels were too boundless; you can go anywhere and do anything in a novel and the reader will take it for granted. Writing for the stage, on the other hand, gives the writer a very small space in which to create action, and the action must exist in the realm of that which can be physically recreated. Constraints, for Beckett, were artistically freeing; for where there is boundlessness there is no real challenge.

To subvert Beckett’s directions and stage a subjectively “more interesting” Endgame is to admit to not being up to the challenge of recreating the play in its original simplicity. It may seem objectively more difficult to create a set littered with cars and broken subway paraphernalia, and I’m sure it’s expensive and impressive and all those sexy adjectives, but to do so is simply to replace narrative bravery with some fancy window-dressing. When a director attempts to win your heart by using a simple text as a canvas for lots of neat visuals and half-baked thematic additives (from the Stage Magazine piece on this current production: “Clov [a servant character] wears African-style garb, send[ing] a clear message on the history of black oppression and the African-American need to escape white domination, just as the characters’ habitation of a public space suggests the plight of the homeless.” Neato.) what he wants to say is, “There is a message buried in the text of this boring old play and by George I’m going to find it.” But what he’s really saying is, “I’m scared to death to do this play the way it’s written because people will think I wasn’t clever enough to come up with a new interpretation of it; so I must add elements that seem to ‘say something’ in order to avoid the responsibility of making an old play exciting to the audience.”

Now there’s some merit to this idea of “making an old play exciting to the audience,” but this director and his ilk are taking the coward’s way out of this conundrum. Yes, theater people know Endgame, just as we know Hamlet and Our Town and The Glass Menagerie. And the reason we love those plays—the reason they’re produced so often and the reason audiences keep paying good money to see them–is because they are great plays. They are great for what they are, not for what they have the potential to be; they are not the canvas, but the painting. Therefore the temptation to tweak and reinvent and reimagine must be resisted so that whatever is great about our beloved medium may live on uncorrupted and continue to inspire young talent to its calling.

I’ve been playing drums for roughly fifteen years now. And though in my youth I played almost every day and with several different bands, I was, until rather recently, a perfectly horrible drummer. I always wanted to play fills and solos, fitting double-kicks and hi-hat trills into any and all available space. I’m sure it was an awful racket, as all the goofing around often caused me to fall out of time and lose the groove. But I thought I was great. I thought I was great because all the other drummers I heard—even on records I loved—were boring. They played straight beats and never showed off any flashy moves. They were steady, but they weren’t creative.

But those steady drummers were wise enough to remember what I had forgotten: that a drummer’s job is to keep the beat. Anything beyond this—any drumming that exceeds the needs and requirements of the song—is a distraction and a nuisance. The musicians and the tricks they possess are not important; what is important is the ability to communicate the song to the audience.

Says that fine playwright and theoretician David Mamet: “[T]he theatrical interchange exists to communicate the text (and so the meaning) of the play to the audience. Anything that does not aid that interchange, detracts from it. The tricky set is an attempt to hijack the interchange. It is a survival of constructivism, of a time and place when the text was suppressed, and its survival today is a form of deconstruction, which is to say vandalism.”

In other words, the play is for the audience, not for the director, to interpret.

In the rehearsal room, it is easy to forget about the playwright, for he or she is almost never in the room and in most cases has been dead for years, if not centuries. But without the playwright, the directors and actors would not exist, so it is important to acknowledge our debt to those scribes by staging their plays as written. If this task proves too difficult, by all means write your own damn play.

This guy really runs off in the mouth. The only way to stop his tirade is to perhaps to shoot him. He throws so many things into the pot, it becomes a foul soup. I hope he learns something at Rosemont. I will not hold it against him that he is from New Jersey, as I was raised there too.

A Response to Michael Fisher’s “Gimmickry in Theater”

Written by Debra Miller

I don’t make it a habit of responding to critics, in the belief that everyone is entitled to his [or her] own [educated] opinion–but I would like to address this one, largely because of his combative, condescending, and omniscient tone. I find it interesting that you would refer to my analysis of ENDGAME as “a glowing review,” yet quote my references to the controversy of changing Beckett’s intent (and later, though not cited by you, to the courts overturning the wishes of art collectors Johnson and Barnes). Was I to condemn the talented actors and artistic team who followed the intent of this interpretive production to a tee, and created impressive performances and designs that were fully compatible with the director’s vision? As you yourself stated in your critique of the LACMA reading of GLENGARRY GLEN ROSS, even though you were offended by the all-female casting, “to Mitchell’s credit, he got some amazingly talented actresses . . .” This production, likewise, got an “amazingly talented” cast; I doubt anyone with any credibility, who has actually seen them, would question the skills of award-winning actors Scott Greer and James Ijames.

The fact that you cited my concerns as well as my praise suggests to me that I succeeded in writing an even-handed review. It was my intent to contextualize the production, and to let prospective audiences of thinking, theater-loving adults consider the controversy, then decide for themselves if this is a show they would like to see, rather than to decree what their opinion should be.

You say, “Last spring, I accepted a gig as an assistant stage manager for a well-known play by a well-known playwright at a theater that, in the interest of good taste, shall not be named.” Was it “good taste” or self-serving cowardice, since you had no qualms, and made no concessions to such social etiquette, when naming and eviscerating the work of other companies by which you were not employed (and which you admittedly did not see)? Though you reference and quote my review, you didn’t credit me, but I have no problem being named; I stand by my review.

You also state: “the only members of the audience who will be able to judge the aptitude of the director’s interpretation are those who have already read the play. Anyone unfamiliar with Endgame . . . will come away thinking that this blasphemous production represents what Samuel Beckett is all about. I can’t imagine a worse introduction to a truly great artist.” I think if audiences were to read my review, they would get an objective indication of the controversy and would not expect a production that adhered to Beckett’s instructions. I also noted, when considering the set and costumes, that they, though well done and meaningful, were not “true to the playwright” and “veered significantly from Beckett’s original directions.”

As I noted in my review, Beckett himself permitted the show at Harvard to go on, agreeing to an out-of-court settlement and a disclaimer in the program. So perhaps your condemnations are misplaced. If you are so deeply offended by the liberties taken with Beckett, why don’t you file a lawsuit against his Estate, which was entrusted with the oversight of his works? Why not criticize Beckett for selling out? Why not demand an explanation from Mamet about granting permission to LACMA? Or is this vitriolic and dictatorial critique, to quote your “neato” colloquialisms, “just for shits?”

And for the record, though I have no statistics to back up my belief, I doubt that these fine female and African-American actors would consider their casting, or contemporary social awareness, “gimmickry.”